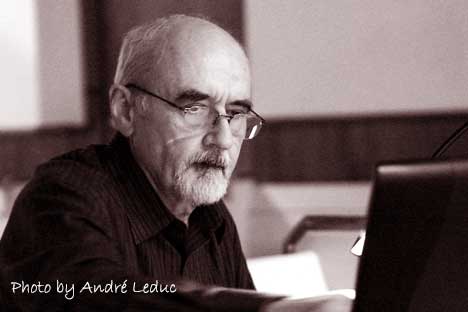

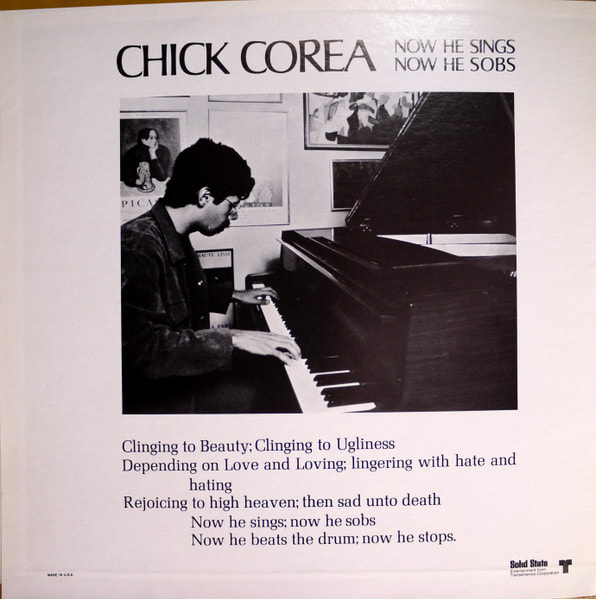

INTERVIEW WITH

DANIEL STUDER

DANIEL STUDER

|

«Vedo che l’aspetto stilistico è sempre meno importante...L'esigenza di esprimersi, di comunicare, anche in un gruppo mi sembra tuttora il motore che spinge le persone verso la musica»

..... «I see that the stylistic aspect is less and less important...The need to express oneself, to communicate, even in a group, still seems to me to be the engine that drives people towards music» |

|

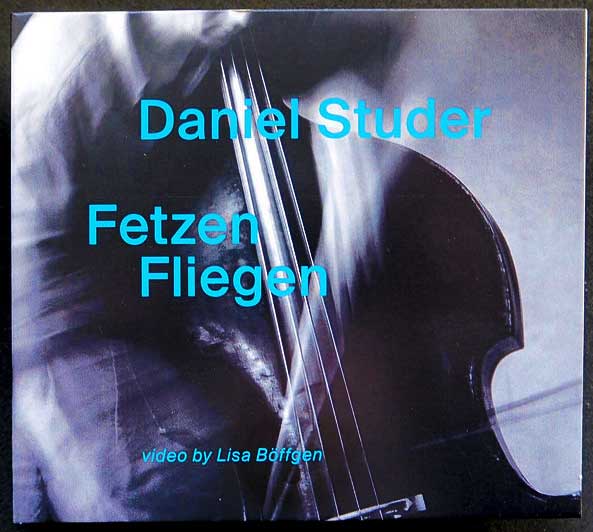

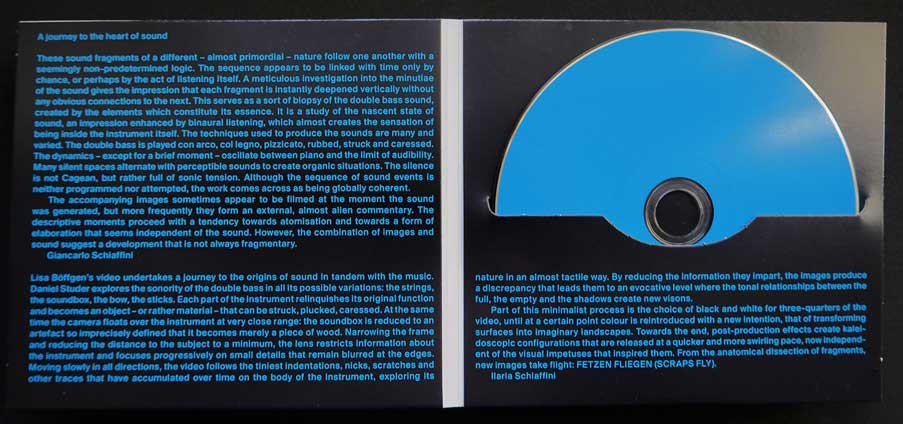

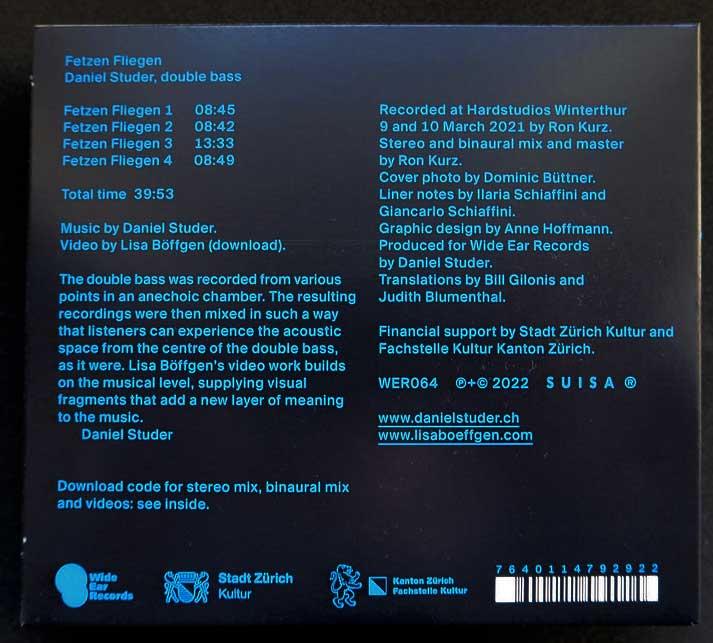

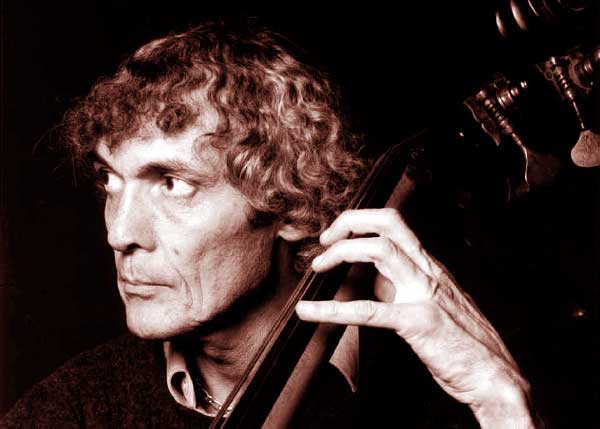

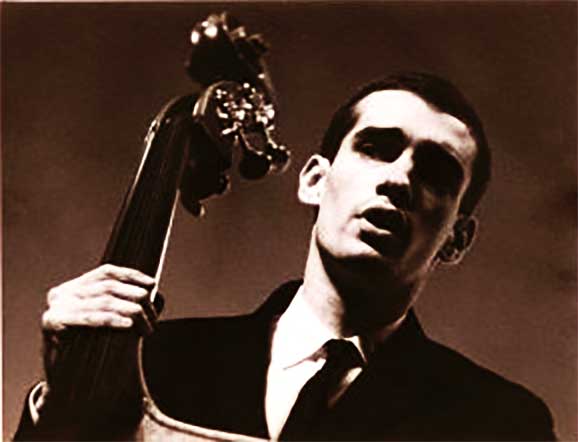

La nostra intervista con Daniel Studer parte da molto lontano, da prima della comparsa della pandemia, tanto che nelle nostre intenzioni avremmo voluto pubblicarla nel 2020. Nel tempo in cui il nostro sito web è stato fermo, Daniel è stato estremamente disponibile e gentile nel mantenere con noi un contatto frequente e aggiornarci sui suoi progetti e sulla sua musica. Nato a Zurigo nel 1961, Daniel ha vissuto quattordici anni in Italia, dal 1981 al 1995, ed è senza ombra di dubbio un musicista abituato a esplorare e oltrepassare i confini non solo del suo strumento, essendo un improvvisatore di grande spessore, ma è anche avvezzo a forme aperte di fusione e commistione sonora e di multiculturalità. Il suo ultimo lavoro in ordine di tempo è il bellissimo e vibrante solo “Fetzen Fliegen”, uscito nel 2022 per la Wide Ear Records, un lavoro che annovera anche le liner notes di Ilaria e Giancarlo Schiaffini, un viaggio “fisico” che Daniel intraprende con il contrabbasso, con incluso un bellissimo video di Lisa Böffgen. Daniel Studer è uno di quei rari musicisti per i quali si può davvero scomodare il concetto di “viaggio”, un percorso libero che si serve dell’approccio materico con lo strumento e il suo suono per tracciare una strada altra. Buona lettura. |

Our interview with Daniel Studer goes back a long way, even before the outbreak of the pandemic, so much so that we had intended to publish it in 2020. During the time our website was down, Daniel was extremely helpful and kind in keeping in touch with us and keeping us up to date with his projects and music. Born in Zurich in 1961, Daniel lived in Italy for fourteen years, from 1981 to 1995, and is undoubtedly a musician accustomed to exploring and pushing the boundaries not only of his instrument, being an improviser of great depth, but also accustomed to open forms of sound fusion and multiculturalism. His latest work is the beautiful and vibrant solo "Fetzen Fliegen", released in 2022 on Wide Ear Records, a work that also includes liner notes by Ilaria and Giancarlo Schiaffini, a "physical" journey that Daniel undertakes with the double bass, including a beautiful video by Lisa Böffgen. Daniel Studer is one of those rare musicians for whom the concept of 'journey' can be truly disconcerting, a free path that uses the material approach with the instrument and its sound to chart a different path. Enjoy reading. |

|

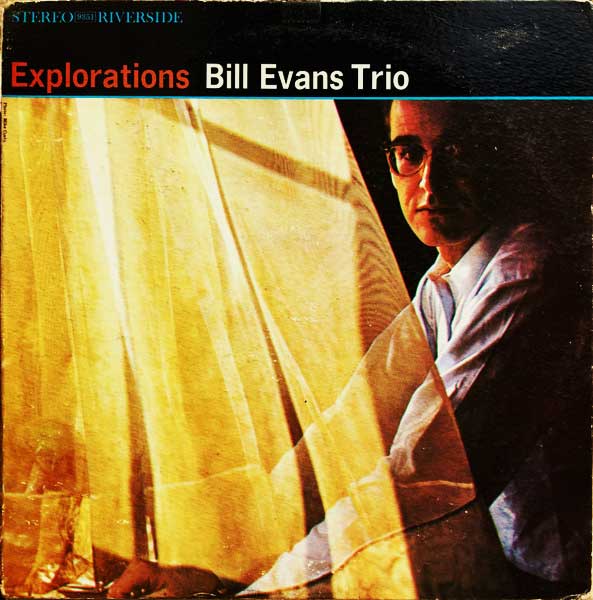

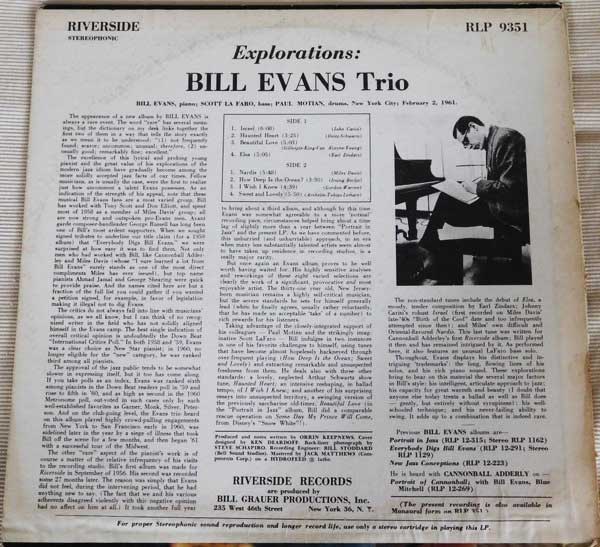

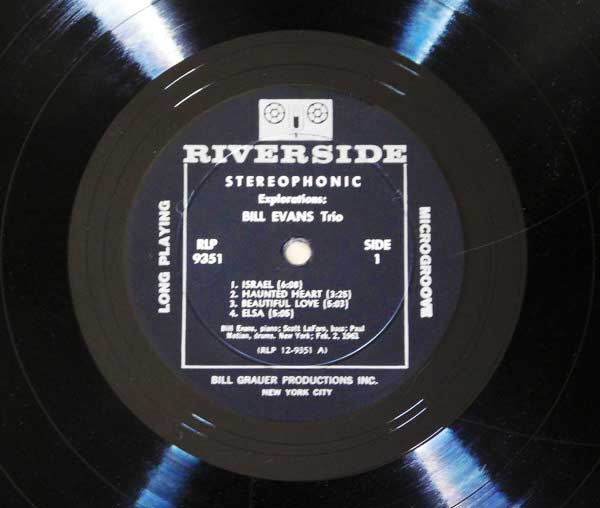

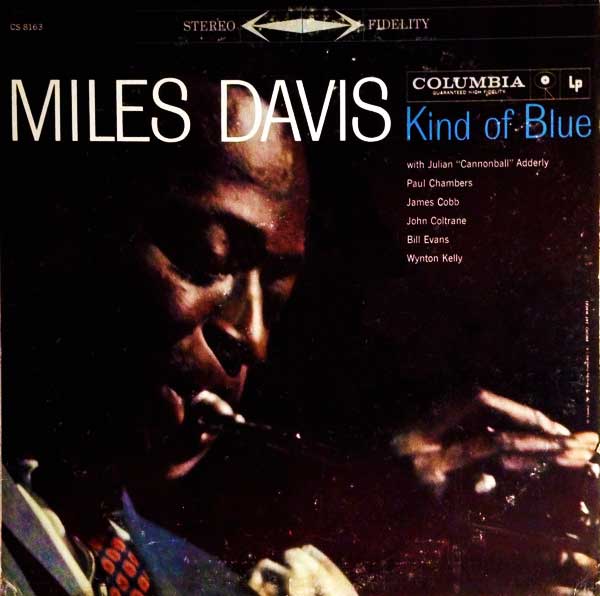

BMF: Daniel, ci racconti dei tuoi inizi e naturalmente della tua scelta del contrabbasso? DANIEL STUDER: Per apprendere le note musicali, quasi come il solfeggio, da noi si imparava a suonare il flauto dolce. Poi iniziò a piacermi il violino, ma il maestro più in gamba se ne andò e avrei dovuto ripiegare sul meno bravo. In campagna non c’erano molti insegnanti e quindi optai per la chitarra. Da adolescente formai un gruppo rock, dove mancava il basso elettrico. Quindi passai a quello strumento. In quella band componevo canzoni, cantavo e appunto suonavo il basso elettrico. L’insegnante di musica, un buon chitarrista da studio di musica leggera, mi introdusse sempre di più nella musica Jazz. Quindi andai in un negozio di musica a Zurigo e comprai un contrabbasso. Non mi resi subito conto dei problemi di trasporto. Era assai difficile portarlo in un piccolo posto non collegato con i mezzo pubblici e chiaramente senza auto. L’insegnante mi diceva di prendere lezioni da Peter Frei. Lui era un insegnante fantastico, mi lasciava molta libertà, mi diceva le cose giuste sia tecnicamente che musicalmente. Fin quasi dalle prime lezioni mi fece ascoltare “Explorations” di Bill Evans e “Kind of Blue” di Miles Davis che da subito mi colpirono moltissimo. |

BMF: Daniel, tell us about your beginnings and of course your choice of double bass…. DANIEL STUDER: To learn musical notes, almost like solfeggio, we used to start to play the recorder. Then I liked the violin, but the good teacher left and I should have settled for a less good one. There weren't many teachers in the country, so I chose the guitar. As a teenager I formed a rock band, but we needed an electric bass. So I switched to that instrument. In this band I composed songs, sang and played the electric bass. The music teacher, a good studio guitarist in pop music, introduced me more and more to jazz music. So I went to a music shop in Zurich and I bought a double bass. I wasn't aware of the transport problems. It was very difficult to take it to a small place with no public transport and, of course, without a car. The teacher told me to take lessons with Peter Frei. He was a fantastic teacher, he gave me a lot of freedom but said the right things both technically and musically. Almost from the first lesson he made me listen to Bill Evans' “Explorations” and Miles Davis' “Kind of Blue”, which impressed me a lot. |

|

BMF: L’Italia ha rappresentato un tassello importante del tuo percorso professionale... vorrei che ci parlassi di questo legame. DS: A vent’anni mi trasferii a Roma. Lavoravo mezza giornata nel rilevamento di strutture architettoniche di Roma sul Palatino. Un lavoro che mi piaceva moltissimo e che ho continuato a lungo. Questo tipo di occupazione mi permetteva di fare molta musica. Sono andato alla Scuola Popolare di Musica di Testaccio, dove ho subito incontrato musicisti con i quali suonare. I concerti in piccoli posti e in locali come il St Louis, l’Alexanderplatz seguirono a breve. Ho accompagnato molti cantanti al St Louis con Riccardo Biseo, poi seguirono ingaggi più interessanti con i fiati come Massimo Urbani, Stefano D’Anna, Steve Grossmann, Bobby Watson, Tony Scott. Mi ricordo con particolare piacere la collaborazione con Barney Kessel come quella con Mike Melillo. Molti di questi lavori li ho ottenuti grazie al batterista Gianpaolo Ascolese. Quindi facevamo il Jazz “classico”, gli “standards”. Dopo un po' ho incontrato Riccardo Fassi, Danilo Terenzi, Eugenio Colombo e molti altri e quindi si facevano pezzi propri. |

BMF: Italy has been an important part of your career... I would like you to tell us about this relationship. DS: I came to Rome in my twenties. I worked half days surveying architectural structures in Rome on the Palatine. It was a job I enjoyed very much and continued for a long time. This kind of work allowed me to do a lot of music. I went to the Scuola Popolare di Musica in Testaccio, where I immediately met musicians to play with. Concerts in small towns and places like St. Louis and Alexanderplatz soon followed. I accompanied many singers at the St. Louis with Riccardo Biseo, then other interesting engagements followed with wind players such as Massimo Urbani, Stefano D'Anna, Steve Grossmann, Bobby Watson, Tony Scott. I remember with particular pleasure the collaboration with Barney Kessel, as well as the one with Mike Melillo. I got a lot of these jobs thanks to drummer Gianpaolo Ascolese. So we did "classical" jazz, the "standards". After a while I met Riccardo Fassi, Danilo Terenzi, Eugenio Colombo and many others, so we were doing our own pieces. |

|

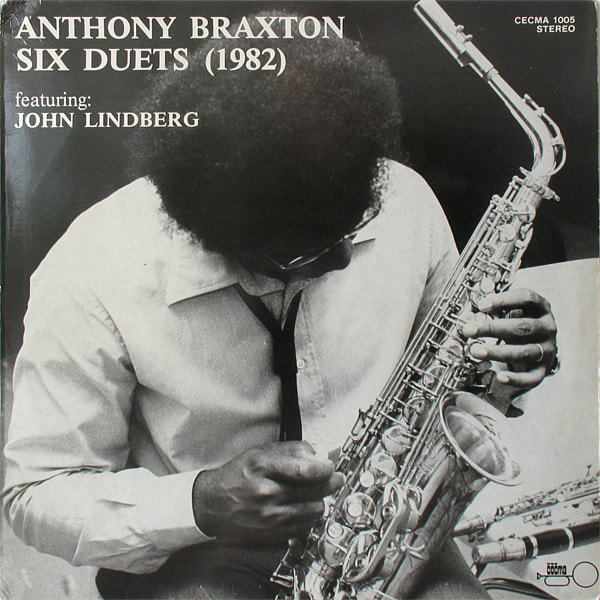

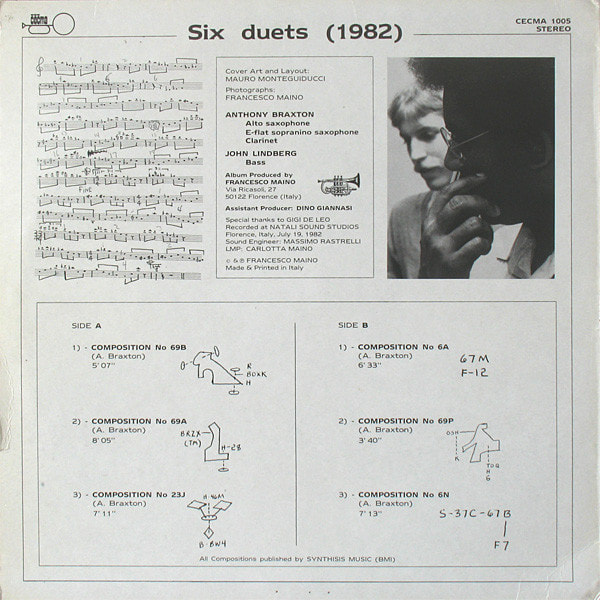

Ho cominciato anche a scrivere e sperimentare, soprattutto con Roberto Stanco e Cristina Majnero. Anche con Riccardo Lay abbiamo formato un duo di contrabbassi. Facevamo pezzi nostri, recitavamo poesie, con una libertà e ironia che ci ispiravano molto. Nella “Braxwood” di Roberto c’era anche Sebi Tramontana con cui formavamo il trio con Roberto Altamura. E quindi vennero i molti lavori con Giancarlo Schiaffini, che mi ha guidato in un mondo musicale aperto in tutte le direzioni. Il mio primo trio d’archi con Benny Penazzi e Massimo Coen è stato proprio il mio primo lavoro che mi piacque moltissimo. In questo gruppo facevamo esperimenti con scritture minime, anche grafiche, fino a una scrittura “completa” per tre archi. Come insegnanti contattavo ogni tanto Furio Di Castri un contrabbassista che stimo molto e nel mondo classico cominciavo a studiare con Sergio Pani dell’orchestra di Santa Cecilia. Quindi facevo anche il conservatorio come privatista. |

I also started writing and experimenting, especially with Roberto Stanco and Cristina Majnero. We also formed a double bass duo with Riccardo Lay. We made our own pieces, reciting poetry, with a freedom and irony that inspired us a lot. In Roberto's 'Braxwood' there was also Sebi Tramontano, with whom we formed a trio with Roberto Altamura. And then there were the many works with Giancarlo Schiaffini, who led me into a musical world open in all directions. My first string trio with Benny Penazzi and Massimo Coen was my very first work that I really liked. In this group we experimented with minimal, even graphic, scores, going on to write "complete" scores for three strings. As a teacher, I was sometimes in contact with Furio Di Castri, a double bass player whom I respect very much, and in the classical world I began to study with Sergio Pani of the Santa Cecilia Orchestra. So I also attended the Conservatory as a private student. |

|

BMF: Il rapporto che hai con l’elettronica è intenso e ricorre spesso nelle tue incisioni e nelle tue esibizioni. Come integri il linguaggio dello strumento acustico con un mondo apparentemente così distante? DS: La musica elettronica mi ha sempre affascinato più come ascoltatore che come esecutore. Mi piacevano molto i lavori di Giancarlo Schiaffini, ma anche il duo di Luca Spagnoletti ed Eugenio Colombo. Poi tornato in Svizzera sono andato all’Elektronisches Studio a Basilea dove Thomas Kessler mi ha introdotto di più in questo mondo, sia nelle “macchine” da usare sia nella storia. A Basilea ho fatto qualche lavoro su nastro e ho composto vari pezzi per strumenti ed elettronica. Con il contrabassista Peter K Frey ho un duo dal 1998. Con lui, che è un bravissimo programmatore, abbiamo eseguito diversi lavori con il computer e live elettronics. Ognuno con il proprio equipment. Un cd documenta un lavoro in studio e dal vivo. |

BMF: The relationship you have with electronics is intense and recurs frequently in your recordings and performances. How do you integrate the language of the acoustic instrument into such a seemingly distant world? DS: Electronic music has always fascinated me more as a listener than as a performer. I really liked the work of Giancarlo Schiaffini, but also the duo of Luca Spagnoletti and Eugenio Colombo. Then, back in Switzerland, I went to the Electronic Studio in Basel, where Thomas Kessler introduced me to this world, both in terms of the 'machines' to be used and the history. In Basel I did some tape work and composed various pieces for instruments and electronics. Since 1998 I have had a duo with the bassist Peter K Frey. With him, who is a very good programmer, we have done various works with computers and live electronics. Each with his own equipment. A CD documents the studio and live work. |

|

BMF: Sei interessato al basso elettrico? E se sì, che tipo di approccio ti interessa sullo strumento elettrico? DS: Il basso elettrico mi interessava quando facevo rock. Poi a Roma in certe occasioni dovevo suonarlo. Non mi piaceva più e sono stato contento quando me lo fregarono. Ne fu sancita la fine. Quando altre persone suonano il basso elettrico mi piace molto. Jan Schlegel, un amico musicista qui a Zurigo suona nel nostro quartetto di bassi. Ci sono tre contrabbassisti (Peter K Frey, Christian Weber ed io) e appunto Jan Schlegel al basso elettrico. Anche mio figlio suona il contrabbasso. Fin da piccolo ha anche suonato il basso elettrico. Ultimamente ho cominciato a lavorare con lo "stick bass“, il contrabbasso elettrico. Ma non lo so ancora dove portano questi esperimenti. Vorrei capire se il suono elettrico più “duro” mi conduca in altri luoghi musicali. Forse anche per un ritorno a ispirazioni più rock. |

BMF: Are you interested in electric bass? And if so, what kind of approach are you interested in? DS: The electric bass interested me when I was playing rock. Then in Rome I had to play it on certain occasions. I didn't like it any more and was glad when they took it away from me. That was the end of it. When other people play electric bass, I like it a lot. Jan Schlegel, a musician friend here in Zurich, plays in our bass quartet. There are three double bass players (Peter K. Frey, Christian Weber and myself) and Jan Schlegel on the electric bass. My son also plays double bass. He started playing the electric bass when he was very young. Lately I have started to work with the 'stick bass', the electric double bass. But I still don't know where these experiments will lead. I would like to see if the 'harder' electric sound takes me to other musical places. Maybe even a return to more rock inspirations. |

|

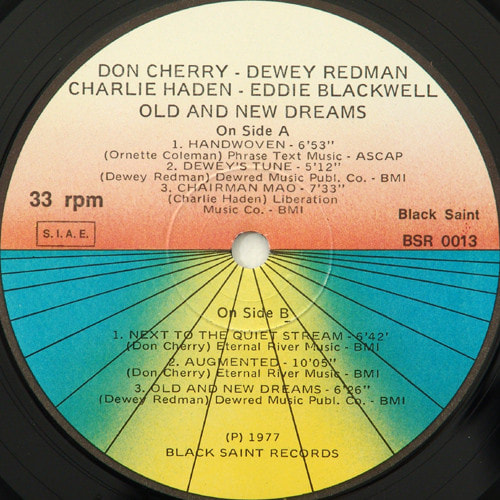

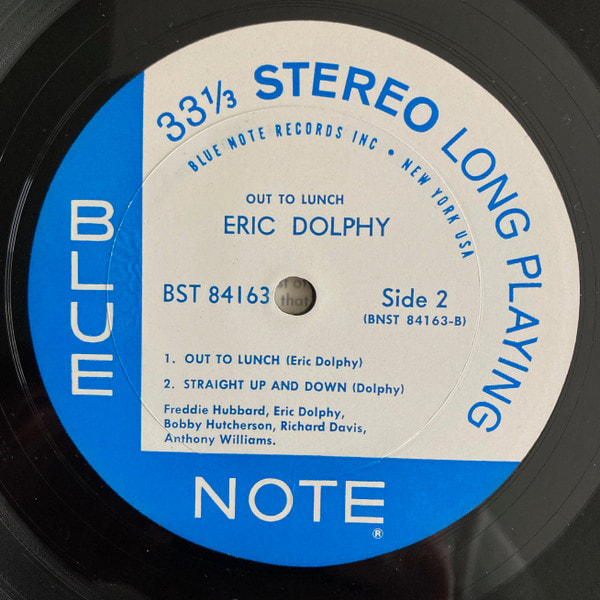

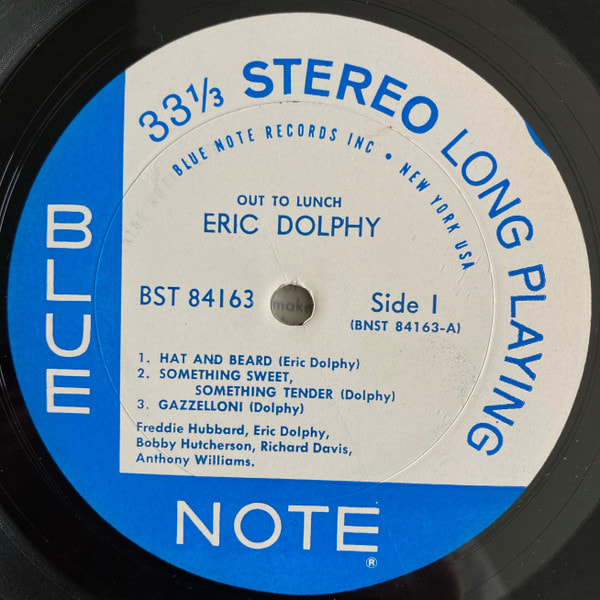

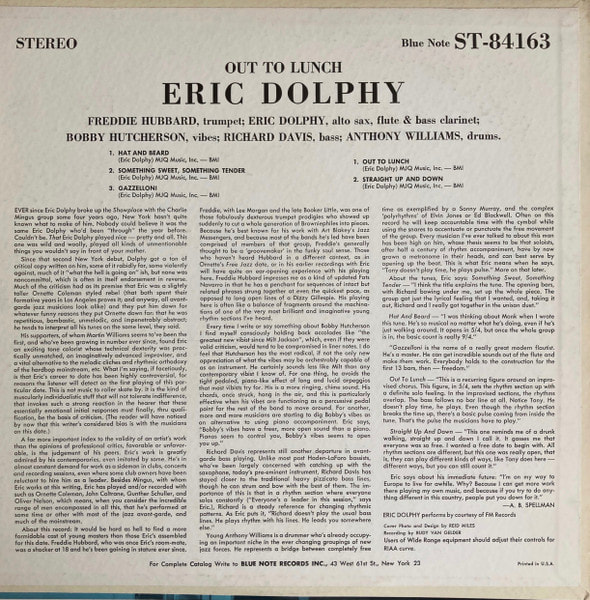

BMF: Occupiamoci della crisi del “supporto” musicale. Il cd sembra destinato a scomparire, il vinile è tornato di moda e non sappiamo quanto sia sincero e spontaneo questo interesse (cioè non legato a mode vintage). Secondo te è in crisi solo il supporto fonografico o proprio il rapporto di fruizione tra musicista e ascoltatori? DS: La musica la senti ovunque. I concerti sono ovunque. Mi sembra che il rapporto tra musicisti e ascoltatori ci sia come sempre, se non di più. Certamente non va sempre di moda lo stesso stile, e anche il mercato sta cambiando. Per me è sempre stato importante incidere un cd quando la musica o un progetto musicale mi sembrava a un buon punto. In questa fase un prodotto materializzato è importante per me. I cd si possono fare a poco prezzo. I negozi e la distribuzione sono ridotti al minimo ma si possono compensare un po' per esempio con internet. Quello che trovo invece molto preoccupante è che le istituzioni publiche e private si stiano ritirando dal sostenere la cultura. Questo succede in tutta Europa ma specialmente in Italia in un modo eclatante. Si investono grandi somme in grandi strutture o progetti per “le masse” e si toglie l’aria alla cultura larga di base. A lungo termine questo avrà effetti preoccupanti. Si va sempre di più verso una cultura di massa che non mette in crisi. Una cultura controllata dall’ alto. Radio, TV e giornali sono sempre più in mano ai privati. La cultura che propongono si vede. |

BMF: Let's look at the crisis of the musical 'medium'. The CD seems destined to disappear, vinyl is back in fashion and we do not know how genuine and spontaneous this interest is (i.e. not linked to vintage fashions). In your opinion, is it only phonographic support that is in crisis, or the relationship between musician and listener? DS: Music is everywhere. Concerts are everywhere. It seems to me that the relationship between musicians and listeners is as strong as ever, if not stronger. Of course, the same style is not always in fashion and the market changes. For me, it has always been important to make a CD when the music or a musical project seemed to me to be at a good stage. At that stage it is important for me to have a materialised product. CDs are cheap to make. Shops and distribution are minimal, but you can compensate a bit with the internet, for example. But what I find very worrying is that public and private institutions are withdrawing from supporting culture. This is happening all over Europe, but it is particularly striking in Italy. Large sums of money are being invested in large structures or projects for 'the masses', and the air is being sucked out of broad-based culture. In the long term, this will have worrying consequences. We are moving more and more towards a mass culture that does not put people out of work. A top-down culture. Radio, television and newspapers are increasingly in private hands. The culture they offer is visible. |

|

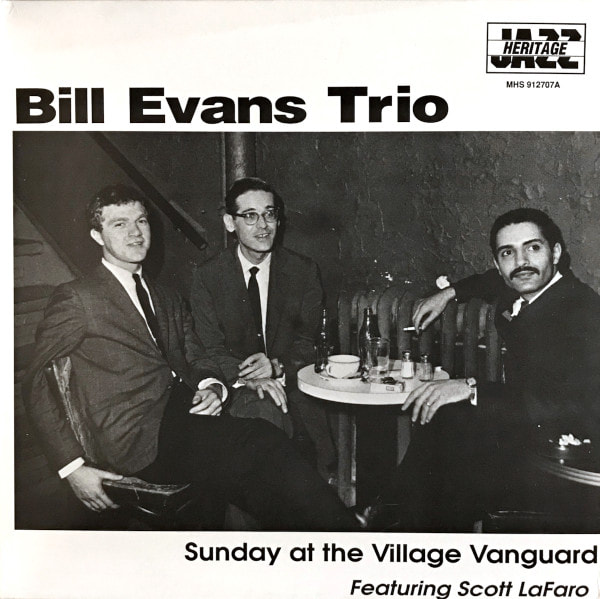

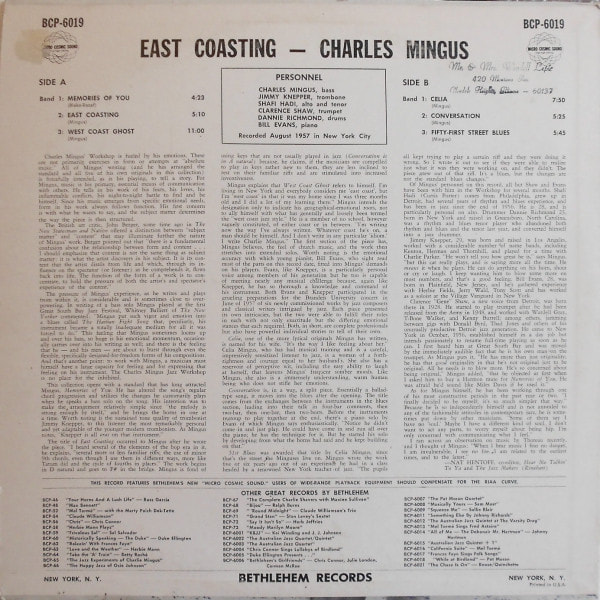

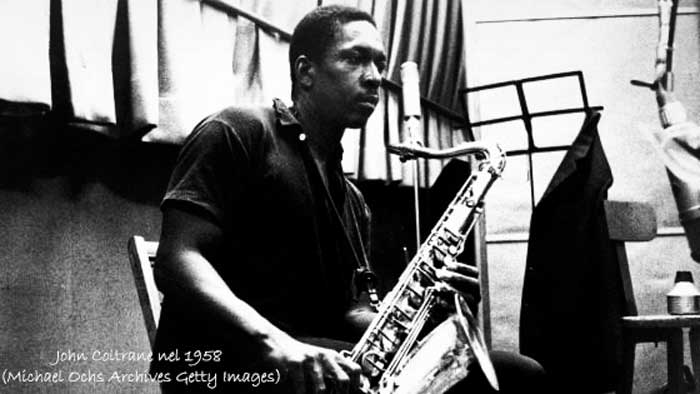

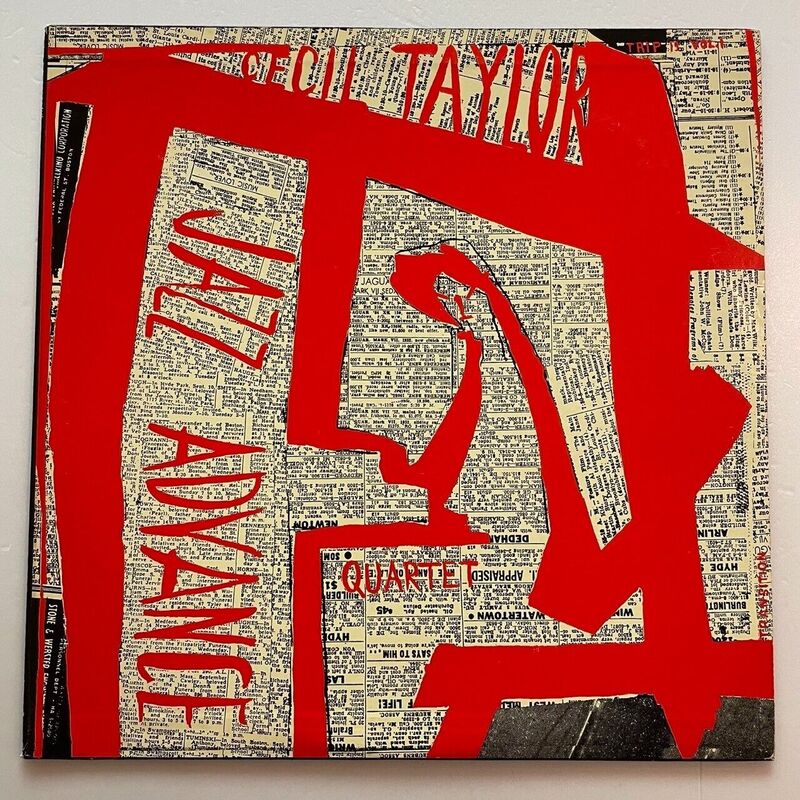

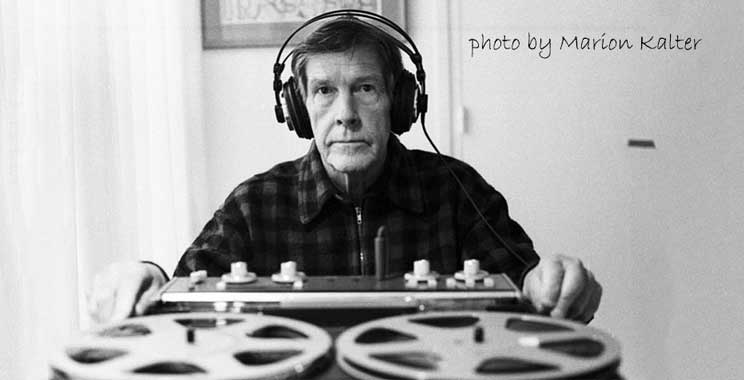

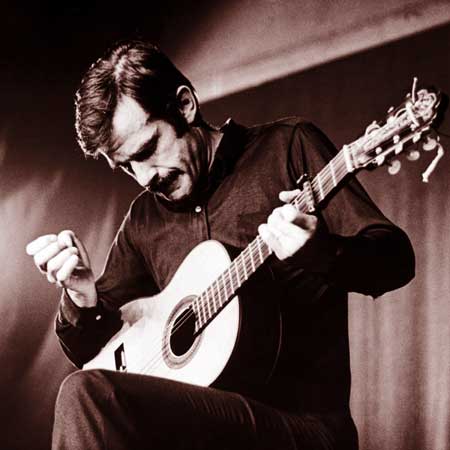

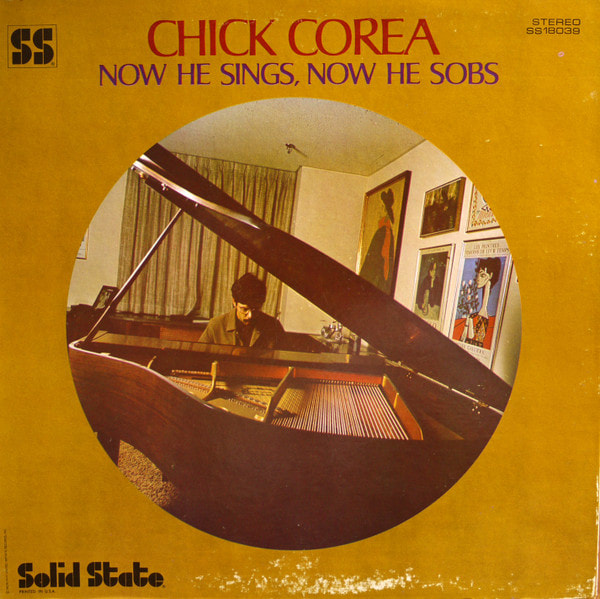

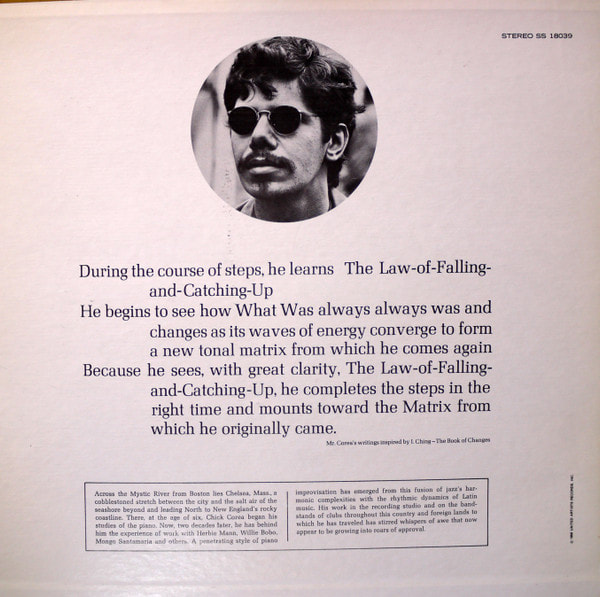

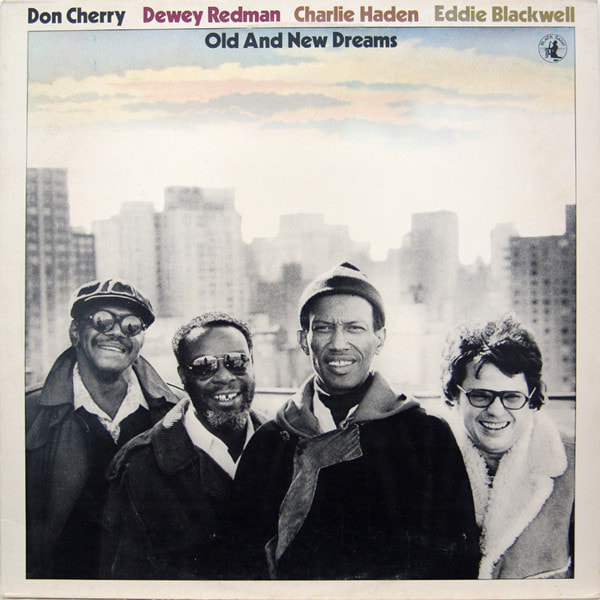

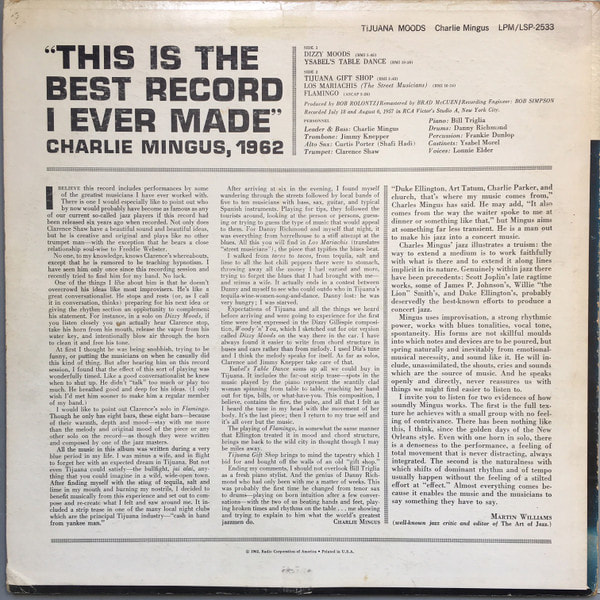

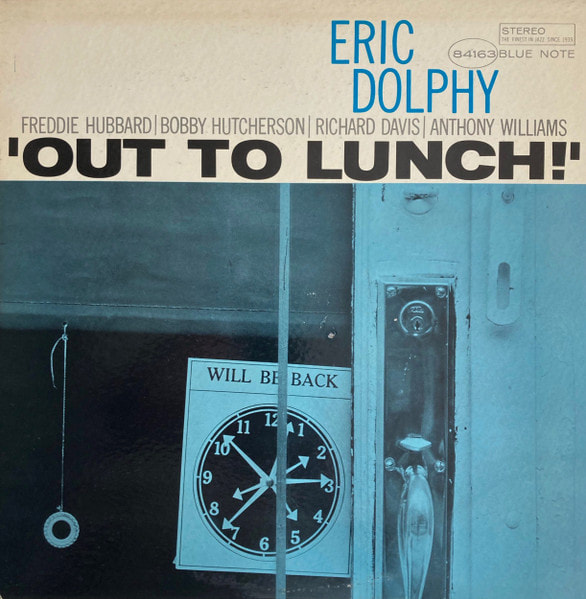

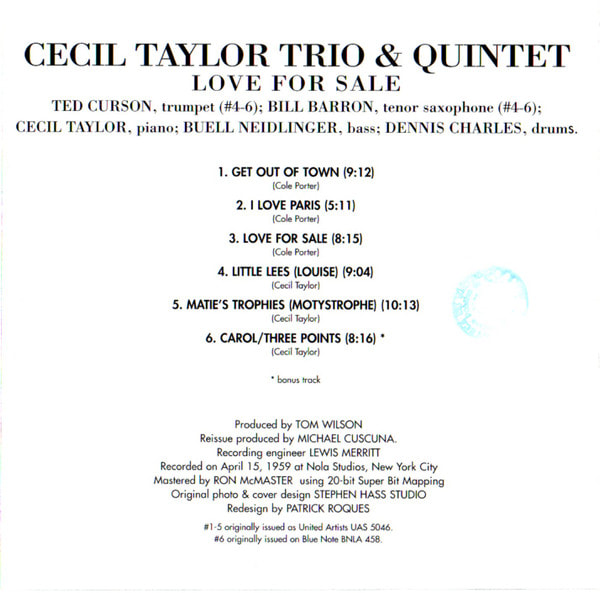

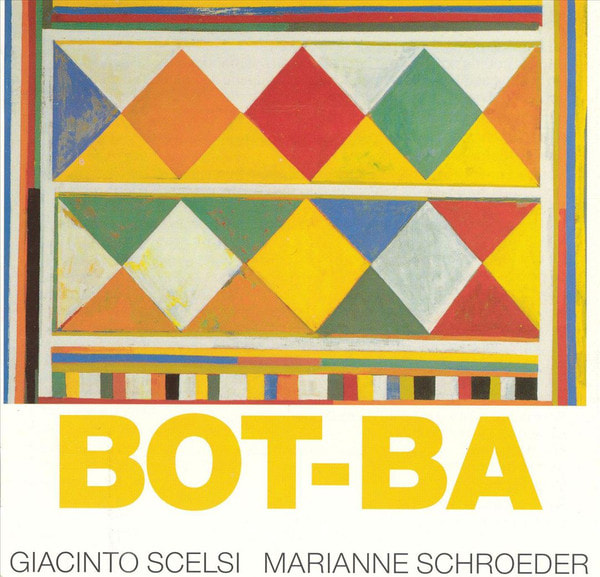

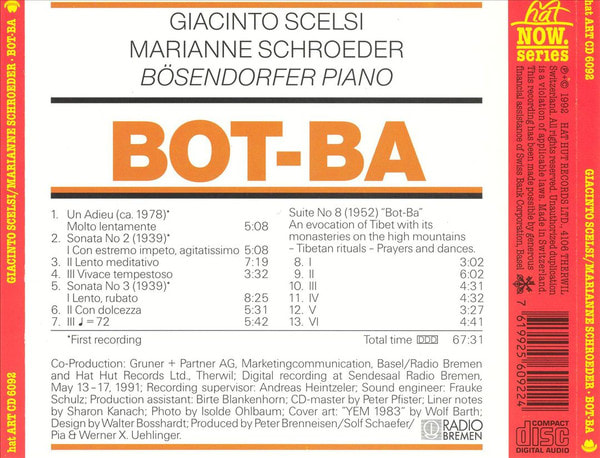

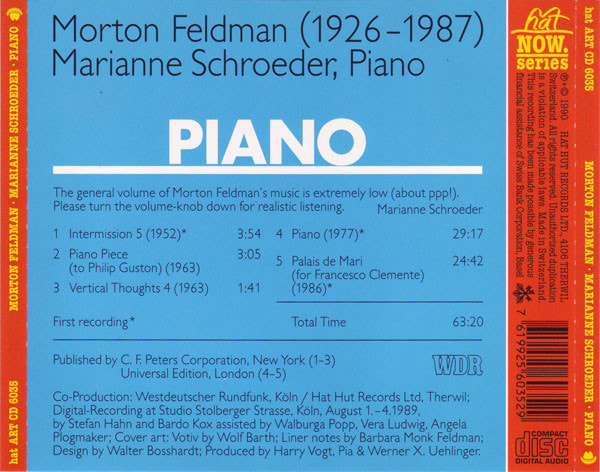

BMF: Una cosa che mi interessa molto è cercare di indagare i tuoi gusti musicali al di là della musica che componi e produci. Chiaramente non attingi solo dal jazz e dalle avanguardie… DS: Mi rendo conto che più vado avanti meno faccio “autocensura”. Ci sono dichi che ascolterò sempre, come il trio con Scott la Faro di Bill Evans, i dischi di Miles Davis, Charlie Mingus, John Coltrane, Cecil Taylor (dal primo del 1955 fino agli anni ottanta). I dischi di Cage, Feldman, Scelsi, Haubenstock-Ramati, Stockhausen, Ligeti. I Beatles, Led Zeppelin, Gentle Giant, Deep Purple… Ma anche Brassens, lo svizzero cantautore Mani Matter, Francesco De Gregori, Lucio Dalla. Musica scritta di ogni tipo (Vivaldi, Frescobaldi, Corelli, Mendelssohn, Debussy, Chopin…). E chiaramente molta musica moderna sia su disco che in concerto. Dischi di musica improvvisata, composizione, etc. Quindi sto ascoltando anche musica di molti amici musicisti. BMF: Voglio chiederti un’opinione circa l’annosa questione del jazz “commerciale”, vale a dire quelle operazioni piuttosto ruffiane di rielaborazioni di brani pop e rock rivisitati da famosi musicisti jazz che ora hanno saturato una fetta dello specifico mercato di genere. Come consideri queste operazioni? DS: Ognuno deve fare le cose che vuole. Ognuno fa delle rielaborazioni o in un modo cosciente o in un modo incosciente. Per quanto mi riguarda, riesco sempre di più a fare la musica che voglio, che mi piace, che sento. È un grande privilegio. |

BMF: One thing I am very interested in is trying to explore your musical tastes beyond the music you compose and produce. Obviously you don't just draw from jazz and the avant-garde.... I find that the further I go, the less I 'self-censor'. There’s a kind of music that I will always listen to, like Bill Evans' trio with Scott la Faro, the records of Miles Davis, Charlie Mingus, John Coltrane, Cecil Taylor (from the first one in 1955 to the 1980s). The records of Cage, Feldman, Scelsi, Haubenstock-Ramati, Stockhausen, Ligeti. The Beatles, Led Zeppelin, Gentle Giant, Deep Purple... But also Brassens, the Swiss songwriter Mani Matter, Francesco De Gregori, Lucio Dalla. Written music of all kinds (Vivaldi, Frescobaldi, Corelli, Mendelssohn, Debussy, Chopin...). And of course a lot of modern music, both on record and in concert. Records of improvised music, compositions, etc. So I also listen to the music of many musician friends. BMF: I would like to ask your opinion on the age-old question of "commercial" jazz, i.e. those rather pandering operations of reworking pop and rock songs, revisited by famous jazz musicians, which have now saturated a part of the specific genre market. How do you see these operations? DS: Everyone has to do the things they want to do. Everyone does rework either consciously or unconsciously. As far as I am concerned, I am more and more able to make the music that I want, that I like, that I feel. It's a great privilege. |

|

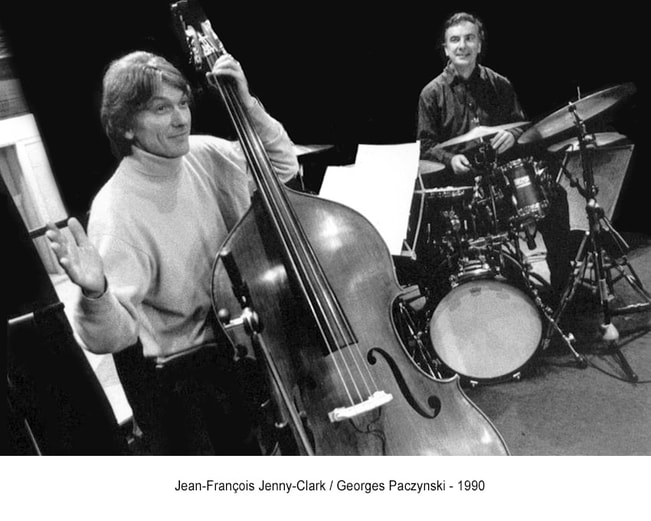

BMF: L’insegnamento è un elemento fondante della tua vita di musicista. Riscontri passione nei giovani musicisti? Capacità di sacrificio? Cosa secondo te spinge i giovani verso il jazz (e verso il contrabbasso)? DS: Vedo che l’aspetto stilistico è sempre meno importante. Musicisti sanno eseguire, improvvisare in vari stili. Sono multifunzionali, anche grazie alle scuole. L'esigenza di esprimersi, di comunicare, anche in un gruppo mi sembra tuttora il motore che spinge le persone verso la musica. BMF: Uno dei musicisti che ha formato di più il mio gusto quando ero ragazzo è stato Jean-François Jenny-Clark, che però, per quanto rispettatissimo ancora oggi, per certi versi non è uno dei nomi più citati quando si parla di contrabbasso. Ti piaceva il suo stile, lo hai conosciuto? DS: Purtroppo è un musicista che non ho seguito come si dovrebbe! E mi sembra di non averlo visto dal vivo o incontrato. |

BMF: Teaching is a fundamental part of your life as a musician. Do you find passion in young musicians? Ability to sacrifice? What do you think attracts young people to jazz (and the double bass)? DS: I see that the stylistic aspect is less and less important. Musicians can perform and improvise in different styles. They are multifunctional, also thanks to schools. The need to express oneself, to communicate, even in a group, still seems to me to be the engine that drives people towards music. BMF: One of the musicians who most influenced my taste as a child was Jean-François Jenny-Clark, who is still respected today, but in some ways is not one of the most mentioned names when it comes to double bass. Did you like his style, did you meet him? DS: Unfortunately he is a musician I have not really followed! And I feel like I haven't seen him live or met him. |

|

|

|