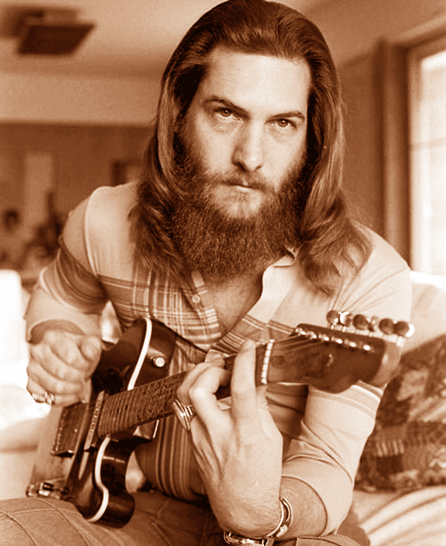

INTERVIEW WITH

MAURO GARGANO

|

|

«The bassist is a figure who always continues to play, even if everythings stop. He looked like a compass to me which gave the direction to the music. I’ve always seen him like a sort of quiet figure but he stood out also for his discretion and for his responsibility. We could consider it as a father figure....» .................... «Il bassista è colui che c’è sempre, anche se il resto si ferma, mi sembrava come una bussola che imprimeva la direzione della musica. Una figura che tutto sommato mi pareva silenziosa, ma che si imponeva anche per la sua discrezione e per la sua responsabilità. Se vogliamo, in definitiva, rappresenta una figura paterna...» |

|

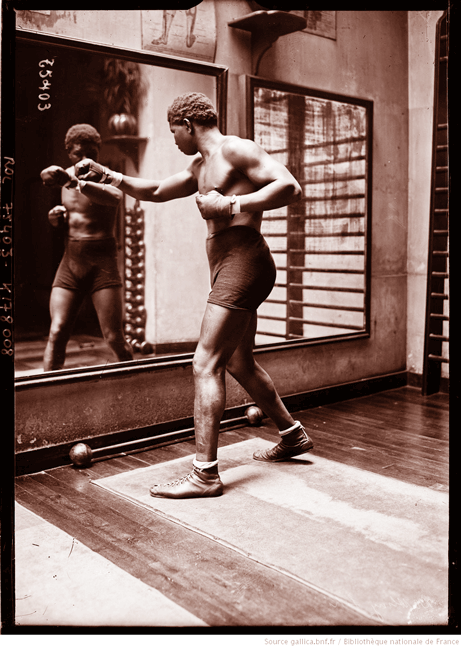

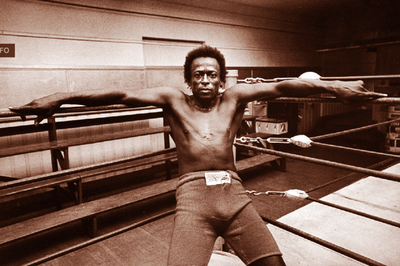

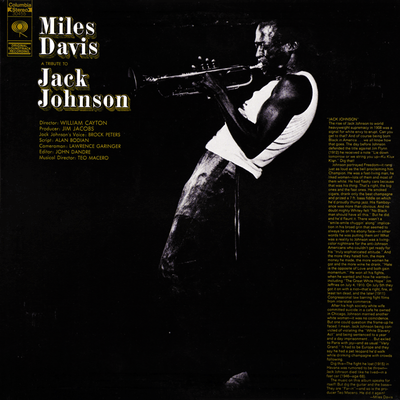

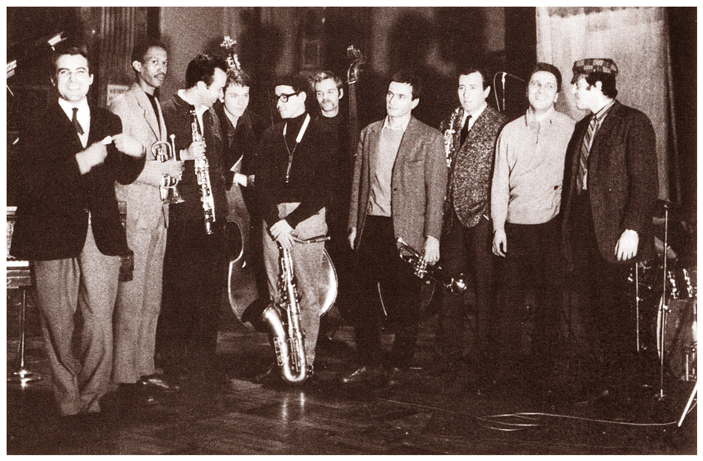

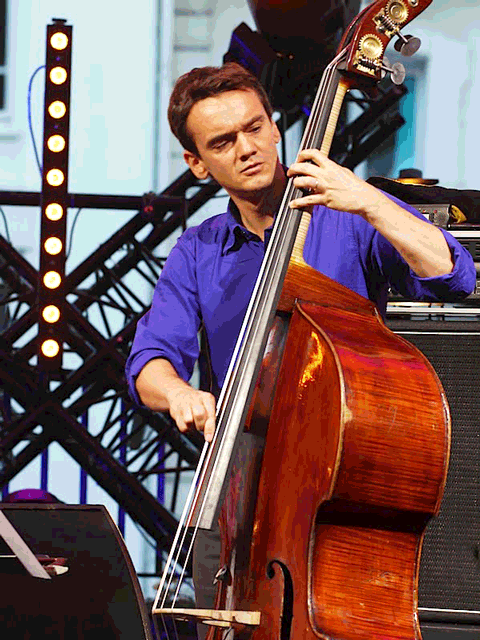

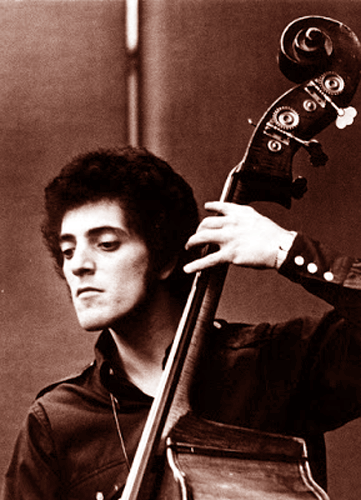

Mauro Gargano, born in 1972, of Bari, is undoubtedly one of the greatest double bass player out there. He’s a musician with a clear sound and a special sensibility. Mauro has been living in France since 1998 and he’s extremely active on the Transalpine as well as European scene. He has realized one of the most beautiful jazz records over the last years, called Suite For Battling Siki which was dedicated to the great and unlucky senegalese boxer who was killed (aged only 28) by a mystery murderer on the streets of New York. Mauro Gargano has indeed a real connection with the universe of boxing and in particular this album is an extremely successful as well as musically surprising tribute, a profound work which is foreign to any formalism; a record on which the compositional style, the urgent need for expression and depth of sound configure a remarkable triad. But Mauro Gargano is also an excellent and creative supporting musician: his very large and magnificent list of collaborations includes - among the others - Nicola Conte, the great René Urtreger, Francesco Bearzatti, Gianni Gebbia, Gaetano Partipilo, Philippe Le Baraillec… |

Mauro Gargano, classe 1972, di Bari, è senza alcun dubbio uno dei migliori contrabbassisti in circolazione. Musicista dal suono deciso e dalla spiccata sensibilità, dal 1998 Mauro vive in Francia ed è estremamente attivo sulla scena transalpina ed europea. È firmatario di uno dei più bei dischi jazz degli ultimi anni, quel “Suite For Battling Siki” dedicato al grande e sfortunato pugile senegalese, ucciso a soli 28 anni da un assassino misterioso nelle strade di New York. Una connessione reale, quella di Mauro Gargano con il mondo del pugilato, e nello specifico un omaggio riuscitissimo e musicalmente sorprendente, con un lavoro di spessore lontano da ogni formalismo, un disco dove classe compositiva, urgenza d’espressione e profondità di suono costituiscono una triade di notevole portata. Ma Mauro Gargano è anche un eccellente e fantasioso accompagnatore, tanto che la sua nutritissima e sontuosa lista di collaborazioni annovera, tra gli altri, Nicola Conte, il grande René Urtreger, Francesco Bearzatti, Gianni Gebbia, Gaetano Partipilo, Philippe Le Baraillec… |

|

One of Mauro’s great qualities is that his desire to deepen and to stay out of some prearranged patterns, goes together with a fast growing career which promises new gems and encounters with other worthy protagonists of jazz; for this amazing upright bassist from Puglia there’s a lot to still compose and play, fortunately for us. Moreover, Mauro is also close to electric bass language which paradoxally pushed him into the arms of the great “cousin”; and he’s also an eclectic listener (which is a key component in difficult times of solipsism and new tunnel visions) who draws up and creates musically sound basis, a process that unfortunately musicians are missing a bit lately. Finally we shall recognize him the considerable courage of not giving into conservatory revanchism which wants nowadays double bass to turn back almost to a rear role typical of some traditional approach as well as of nonsense cycles and recycling trends. This great artist embodies – as his other valuable fellow of the instrument – the most intriguing and appropriate role of modern double bass, which is halfway between the tradition and clearly the risk. For Mauro Gargano and obviously for us of Bass, My Fever, when a rigid technique as well as the orthodoxy take over the courage and the fighting one can only lose himself. |

Una delle grandi qualità di Mauro è che la sua curiosità, il suo desiderio di approfondire e non finire in schemi prefissati, vanno di pari passo con una carriera in crescendo che promette nuove gemme e incontri con altre anime nobili del jazz, per il contrabbassista pugliese c’è ancora tanto da scrivere e suonare, per nostra fortuna. Inoltre, Mauro è anche legato al linguaggio del basso elettrico, che per paradosso lo ha sospinto tra le braccia del gigantesco cugino; ed è, componente questa fondamentale in tempi grami di solipsismo e nuovi paraocchi, un ascoltatore onnivoro che trattiene, rielabora e crea su solide basi di conoscenza, un processo che malauguratamente si sta un po’ perdendo. Infine gli va attribuito anche il notevole coraggio di non cedere al revanscismo conservatore che vuole oggi, per assurdità di cicli e ricicli, il contrabbasso tornare quasi a un ruolo tradizionalmente di retrovia. Questo grande artista incarna, come altri suoi validi colleghi di strumento, il ruolo più intrigante e sensato del contrabbasso contemporaneo, sospeso e in perenne movimento tra la tradizione e naturalmente il rischio. Per Mauro Gargano, e anche per noi, quando la tecnica fredda e l’ortodossia si sostituiscono al rischio e alla battaglia, c’è solo da perdere e smarrirsi. |

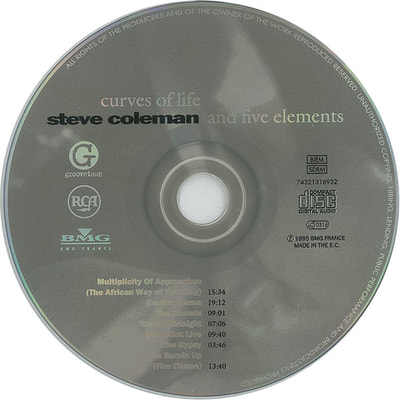

MAURO GARGANO'S MAIN DISCOGRAPHY

|

|

|

|

|

|

BORN TO "FIGHT" FOR THE MUSIC: |

PRONTO A "COMBATTERE" PER LA MUSICA: INTERVISTA A |

|

BMF: Let’s start from your beginnings. What about your first approch to the instrument and why did you choose it? Mauro Gargano: Since I was a kid I’ve been fascinated by bass, but I got a late start. Before I had the opportunity to play earlier when I was fifteen, I’ve been trying to emulate with my voice the lines of the bands which I liked as for instance Police, Simple Minds, Pino Daniele, David Bowie, Working Week, UB40, U2, poi Beastie Boys, Run-DMC, BB King, Roberto Ciotti, Johnny Winter, Steve Cropper, as well as much of the new wave made in England… I’ve always liked the deep sound and the substance of bass expression. I adored that frequency which supported the drums and which was used to order strongly the throbbing to the dance. I was also fascinated by the role of the bassist inside the band, the solidity which he embodied in front of the other members of the group. He was a shoulder to lean on in every moment, and a base for the voice as well as for every kind of solo. As a kid, as many others, I wasn’t able to make a clear distinction between the sound of the bass and the other instruments, I had to concentrate just on it so as to catch its secrets and discover the amazing hidden universe which represented. The bassist is a figure who always continues to play, even if everythings stop. He looked like a compass which gave the direction to the music. I’ve always seen him like a sort of quiet figure but he stood out also for his discretion and for his responsibility. |

BMF: Partiamo proprio dai primordi. Come hai iniziato e perché hai scelto il basso? Mauro Gargano: Sin da quando ero piccolo ero affascinato dal basso, ma ho incominciato tardi. Prima di poter essere in grado di suonare, già verso i quindici anni cercavo di riprodurre con la voce le linee dei gruppi che mi piacevano, come quelle dei Police, Simple Minds, Pino Daniele, David Bowie, Working Week, UB40, U2, poi Beastie Boys, Run-DMC, BB King, Roberto Ciotti, Johnny Winter, Steve Cropper, e molta new wave inglese… Mi piaceva il suono grave, lo spessore della voce del basso. Adoravo quella frequenza che supportava la batteria, e che imponeva fortemente la pulsazione della danza. Ero affascinato anche dal ruolo del bassista nel gruppo, alla solidità che rappresentava per gli altri. Una spalla musicale su cui appoggiarsi in ogni momento, ed una base per la voce, e per i solismi di vario genere. Da piccolo, come molti, non riuscivo ad identificare in maniera netta il basso, mi dovevo concentrare esclusivamente su di “lui” per carpirne i segreti, e scoprirne l’affascinante mondo sommerso che rappresentava. Il bassista è colui che c’è sempre, anche se il resto si ferma, mi sembrava come una bussola che imprimeva la direzione della musica. Una figura che tutto sommato mi pareva silenziosa, ma che si imponeva anche per la sua discrezione e per la sua responsabilità. |

|

We could consider it as a father figure. I wonder if it originates from my early need to identify myself in a father model. Maybe I’ve played subconsciously this role which in my real life passed away when I was thirteen. So I started late, when I was about eighteen. My mother didn’t want me to play because I had already many distractions outside school environment, she didn’t want me to have many more. I did not get good grades and I couldn’t concentrate. Despite everything I seriously considered to play the bass when I was fifteen/sixteen, but the time was never right anyway. Then when I accepted some works on weekends, I saved up some money in order to face that challenge. When I was eighteen I finally bought an EKO bass and a FBT Amp (50 watt) that a brother of one of my school mates sold me. I began to study it by myself and later by taking some lessons from Vito Di Modugno (bassist and organist) in a music school called “Il Pentagramma di Bari”, which was a context were many generations of musicians of Bari grew and which continues to be a really vibrant crossroad for many artists. |

Se vogliamo, in definitiva, rappresenta una figura paterna. Chissà se questa mia predilezione derivi da un mio bisogno giovanile di ritrovarmi in un modello paterno. Ho forse incarnato inconsciamente questo ruolo che nella vera vita mi é venuto a mancare quando avevo tredici anni. Quindi ho iniziato tardi, verso i diciotto anni. Mia madre non voleva che suonassi perché avevo già parecchie disattenzioni al di fuori del quadro scolastico, e non voleva che ne aggiungessi altre… Andavo maluccio a scuola, ed ero spesso molto distratto. Nonostante tutto avevo già maturato l’idea di suonare il basso verso i quindici-sedici anni ma non era mai il momento giusto. Poi dopo aver accettato dei lavoretti il fine settimana, misi da parte qualche soldo per azzardare l’impresa. A diciotto anni comprai finalmente un basso EKO ed un amplificatore FBT (50watt) dal fratello di un mio compagno di classe del liceo. Incominciai a studiarlo inizialmente da autodidatta, e poi prendendo delle lezioni con Vito Di Modugno (bassista ed organista) in una scuola di musica, "Il Pentagramma di Bari", una realtà che ha formato molte generazioni di musicisti baresi e che ancora adesso é un crocevia molto attivo per molti. |

|

BMF: You have studied in French and you’ve been living there for a long time. This french phase allows me to ask you if you see any specific difference between the approval from the italian audience and the attention paid by the french public about jazz… MG: There are many similarities between both italian and french audience, mostly as regards the age range of the listeners, which is quite old, I think. In the Eastern European countries, for instance, the public of the concerts is very young, and it’s really fashionable to go to jazzclubs. In Italy maybe this kind of interest is diasappearing also because of “TV invisibility” which involves aur music, as well as for the fact that they do invest considerable sums of money mostly in the promotion of Pop music. In France there’s more attention for what is modern and contemporary, because the State subsidises creativity, artistic structures and in general new proposals also through countless competitions. Especially young people benefit from that. And this is good. Although lately this has gotten out of hand in my opinion… They have imposed even a quota on festivals so as to include under 30 artists both in the schedules and in the line-ups of the groups, by requiring that at least 1/3 of the musicians belongs to the “giovan” under 30 category. This isn’t wrong because I’ve always found interesting to bring together and to relate different generations of musicians. But in Italy I think that it takes place spontaneously, while in French there’s mainly a sort of climate of war between generations which I’ve found quite fruitless since the first steps on french scene; anyway if they made these decisions, I assume there's a reason.. In Italy I think that the context is more nuanced and less adversarial, even though there are also on italian landscape some moods connected to the excessive visibility of the same artists who afterall do a lot for emphasizing young artists. I’m thinking in particular of Enrico Rava who always involves talented young musicians in his projects, not to mention Paolo Fresu who even produces them on his Label Tuk, or Roberto Gatto and other excellent italian musicians who drive their own students by forming a federation of people. All these things are really positive. |

BMF: Hai studiato in Francia e da tempo risiedi lì. Questa tua base francese mi consente di chiederti se individui precise differenze tra l’accoglienza che viene riservata al jazz qui in Italia rispetto a quella riservata dai nostri cugini transalpini… MG: Il pubblico degli appassionati é molto simile fra l’Italia e la Francia, soprattutto per quanto riguarda la fascia di età dei suoi fruitori, abbastanza avanzata direi. Nei paesi dell’Est-Europa per esempio il pubblico dei concerti é molto giovane, e va molto di moda frequentare i jazzclub. Mentre forse da noi questo tipo di interesse sta scomparendo anche per colpa della “invisibilità televisiva” della nostra musica, e per il fatto che grossi investimenti culturali vadano per la promozione della Pop music. In Francia c’é un maggiore interesse per ciò che é moderno e contemporaneo, in quanto lo Stato francese sovvenziona la creatività, le residenze artistiche creative, ed in generale le nuove proposte, anche attraverso innumerevoli concorsi. In particolar modo i giovani ne traggono giovamento. Ed è un bene. Anche se ultimamente si sta esagerando secondo me: hanno imposto addirittura delle quote nei festival per inserire giovani artisti under trenta, sia nei palinsesti che nell’organico dei gruppi, imponendo che almeno 1/3 dei musicisti facciano parte della categoria “giovan” under trenta. Ciò non é sbagliato perché ho sempre reputato interessante far incontrare e mettere in relazione generazioni diverse di musicisti. In Italia trovo che ciò avvenga spontaneamente. Mentre in Francia c’é più un clima di guerra fra generazioni che ho trovato alquanto sterile sin dai miei primi passi sulla scena francese, poi se hanno deciso di prendere certe decisioni così nette un motivo ci sarà... In Italia trovo che ciò sia più sfumato e meno conflittuale, nonostante ci siano anche sulla scena italiana malumori legati alla visibilità molto forte di alcuni, che però tutto sommato fanno anche molto per mettere i giovani in luce. Parlo per esempio di Enrico Rava che prende sempre giovani talentuosi nei suoi gruppi, e Paolo Fresu che addirittura li produce con la sua etichetta Tuk; o ancora a Roberto Gatto, ed altri bravi musicisti italiani che spingono i propri allievi a prodursi creando dei movimenti che possano federare tante persone. Tutto ciò é molto positivo. |

|

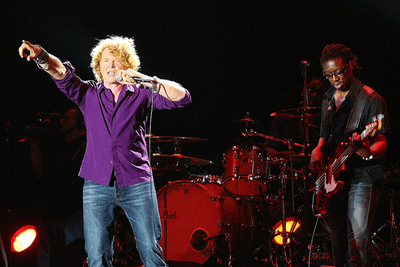

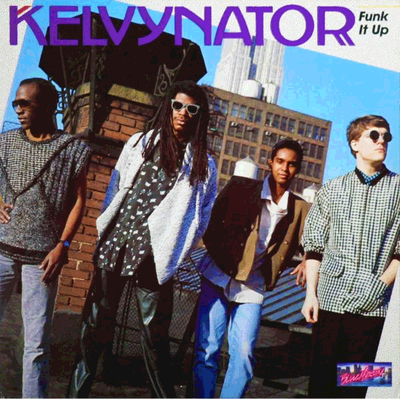

BMF: What about your first influences both as regards bass and generally speaking? MG: As I told above when I didn’t play electric bass yet I liked a lot pop rock music (Genesis, Police, Simple Minds, Depeche Mode, Yes, Beatles, Supertramp, EL&P, Duran Duran, U2, Sting, Working Week, Pino Daniele, Zucchero, Dalla, Simply Red), the soundtracks which I found in my house (Once Upon a Time in America, The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, Amarcord, Rumble Fish with the amazing music composed by Stewart Copeland, The Blues Brothers, Michael Nyman on movies directed by Peter Greenaway), funky music (Earth Wind &F., Average White band, Tower of Power, Bootsy Collins, James Brown, Maceo Parker, Defunkt, Kelvinator X…), blues and blackmusic in general (especially the great James Jamerson, Donald Duck Dunn, Chuck Rainey, Carol Kaye on bass…) and then I had a fusion phase as a kid which reflected my first years of study of electric bass (Stanley Clarke, Jaco Pastorius, Michael Manring, Patitucci, Anthony Jackson, Alphonso Johnson, Brian Bromberg, Will Lee, Pops Popwell, Neil Stubenhaus, Marcus Miller, etc.). And then over time - while I was improving the quality of my listening preferences also thanks to the radio (the splendid Radio Rai broadcast that I was used to record on audio tape) and all the vinyls that I borrowed from Luca Conte (Nicola Conte’s brother) – finally I came to double bass, jazz, european jazz, free and soul jazz as well as boogaloo… |

BMF: Quali sono state le tue prime influenze, tanto sullo strumento che in generale? MG: Come dicevo prima, quando ancora non suonavo il basso elettrico mi piaceva tanto il pop-rock (Genesis, Police, Simple minds, Depeche Mode, Yes, Beatles, Supertramp, EL&P, Duran Duran, U2, Sting, Working Week, Pino Daniele, Zucchero, Dalla, Simply Red), la musica delle colonne sonore che trovavo in casa (C’era una volta in america, Il buono, il brutto, il cattivo, Amarcord, Rusty il selvaggio con la splendida musica di Stewart Copeland, i Blues Brothers, Michael Nyman dei films di Peter Greenaway), il funk (Earth Wind &F., Average White band, Tower of Power, Bootsy Collins, James Brown, Maceo Parker, Defunkt, Kelvynator…), il blues, e la black music in generale (con i grandi James Jamerson, Donald Duck Dunn, Chuck Rainey, Carol Kaye al basso…) poi ho avuto una fase fusion che corrispondeva ai miei primi anni di studio del basso elettrico (Stanley Clarke, Jaco Pastorius, Michael Manring, Patitucci, Anthony Jackson, Alphonso Johnson, Brian Bromberg, Will Lee, Pops Popwell, Neil Stubenhaus, Miller, etc.). Poi con il tempo, migliorando la qualità dei miei ascolti anche grazie alla radio (le meravigliose trasmissioni di Radio RAI che registravo in audiocassetta), ed i vinili che mi prestava Luca Conte (fratello di Nicola Conte) arrivò anche il contrabbasso, il jazz, il jazz europeo, il free jazz, il soul jazz ed il boogaloo... |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

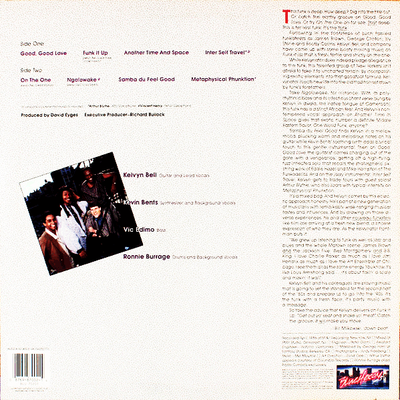

The first upright bassists whom I listened to with a great pleasure and who were for me an incentive to deepen the expertise of the instrument, were Mingus, Paul Chambers, Steve Rodby and Charlie Haden with Pat Metheny, Marc Johnson with Peter Erskine and Abercrombie, but also Bill Evans, Patitucci clearly, Ray Drummond together with Kenny Barron and George Coleman, Palle Daniellson along with John Taylor’s Trio, and Mingus, Keith Jarrett together with Peacock... I went to watch Patitucci in concert, Tarus Mateen when he was so young, Miroslav Vitous, Paolino Dalla Porta, Charlie Haden, Reggie Washington together with Steve Coleman, Lonnie Plaxico, Furio di Castri, and not to mention all the many double bass players form Bari on the stage of Strange Fruit, that is to say a club of the period which helped so much to instill in those young enthusiasts the obsession with jazz. I fell madly in love with double bass and after few years I decided to test it so as to learn to play it. I took by now the decisive step, and I was so much fascinated by its sound that I consciously decided to put aside electric bass, that for a little while stayed beside the acoustic instrument. I took lessons for many years from Maurizio Quintavalle, an excellent upright bassist as well as teacher from Bari, who made me discover and study the style of Jimmy Blanton, Oscar Pettiford, Sam Jones, Wilbur Ware, Paul Chambers, Mingus, Dave Holland, Marc Johnson… |

I primi contrabbassisti che ascoltai con grande piacere e che per me furono di stimolo ad approfondire la conoscenza dello strumento furono Mingus, Paul Chambers, Steve Rodby e Charlie Haden con Pat Metheny, Marc Johnson con Peter Erskine e Abercrombie, ma anche con Bill Evans, Patitucci naturalmente, Ray Drummond con Kenny Barron e George Coleman, Palle Danielsson con il trio di John Taylor, e Mingus, Keith Jarrett con Peacock... Dal vivo vidi Patitucci, Tarus Mateen giovanissimo, Miroslav Vitous, Paolino Dalla Porta, Charlie Haden, Reggie Washington con Steve Coleman, Lonnie Plaxico, Furio di Castri, ed anche tanti ottimi contrabbassisti baresi sul palco dello Strange Fruit, un club dell’epoca che contribuì tantissimo ad instillare la malattia del jazz a tanti ragazzi baresi. Mi innamorai quindi perdutamente del contrabbasso, e dopo pochi anni decisi di provarne uno per imparare a suonarlo. Oramai il passo l’avevo fatto, ed ero talmente affascinato da quel suono che consapevolmente decisi di mettere da parte il basso elettrico che per molto poco tempo affiancò lo strumento acustico. Presi lezioni per svariati anni da Maurizio Quintavalle, un eccellente contrabbassista e didatta pugliese, che mi fece scoprire e studiare lo stile di Jimmy Blanton, Oscar Pettiford, Sam Jones, Wilbur Ware, Paul Chambers, Mingus, Dave Holland, Marc Johnson… |

|

|

|

|

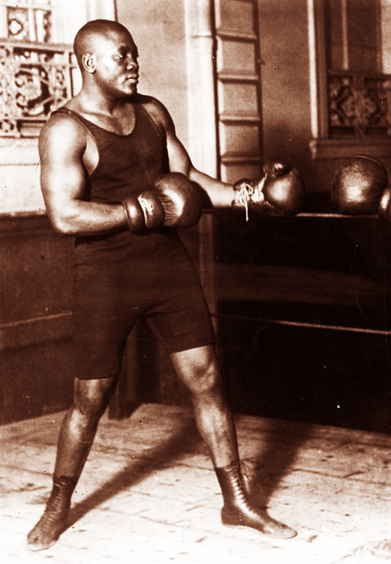

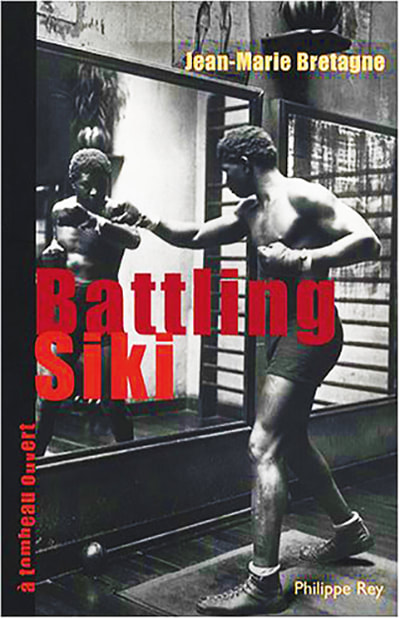

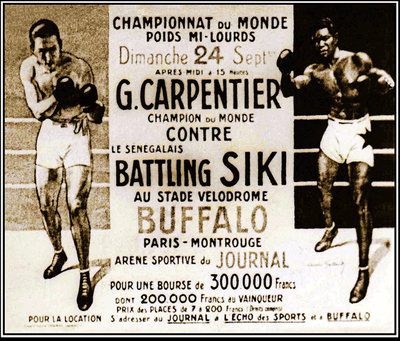

BMF: “Suite for Battling Siki” issued last year, your second solo album after the one recorded with Mo’ Avast Band in 2012, had great success and we also like it very much. Would you like to tell us how was that project born and about its connections with the universe of boxing? MG: That project comes from a festival called “Bari in Jazz” in 2011 and was commissioned to me by Roberto Ottaviano (who was the festival director at that time) in order to indirectly “pay tribute” to Mile Davis through one of both passions which brought us together that is to say boxing. I’ve been playing it at amateur level from sixteen to twenty-three-year-old. Miles honored Jack Johnson, the first Afro-American champion in his namesake album; in the same way I paid a tribute to Battling Siki, the first African champion in the history of boxe in that project for the festival. The idea inspired me very much because I began a deep research before deciding the theme of the project; then, also thanks to the enthusiasm of Roberto who found it interesting, I was determined to put on paper everything. I started to compose the music in the form of “suite” in six movements like the 6 rounds of the match between Battling Siki and Georges Carpentier which made him world champion. Then while I was reading a beautiful book dedicated to him that was written by a sport reporter called Jean Marie Bretagne on a Paris-Milan flight, I felt the urge to write a dialogue and give voice to the SIKI’s character. So with the greatest naturalness I began to compose without worrying about form, punctuation, meaning, letting the words flow through a stream of thoughts and emotions. The result of that was an imaginary dialogue between the boxer and his coach during the interval of one minute between rounds. I tried to focus on the humanity of the character and his own inside torment which was aroused by the fact that his couch had sold the match and he tried to persuade him to nock out… The legend, indeed, has it that the Carpenter’s clan, a champion in decline, made a deal with the Siki’s clan to get him to go down at a pre-defined round. I tried to express in the background of this dialogue also this incident, by intertwining them with music movements. |

BMF: “Suite for Battling Siki” dell’anno scorso, il tuo secondo album solista dopo quello con la Mo’ Avast Band del 2012, ha ottenuto ottimi riscontri e anche a me è piaciuto davvero molto. Ci racconti come è nato quel progetto e delle sue connessioni con il mondo del pugilato? MG: Il progetto é nato in occasione del festival “Bari in Jazz” del 2011, e mi fu commissionato da Roberto Ottaviano, allora direttore del festival, per “omaggiare” Miles Davis visto che il festival di quella edizione era dedicato a lui. Decisi quindi di scrivere un omaggio “indiretto” a Miles Davis attraverso una delle passioni che avevamo in comune: il pugilato, che ho praticato a livello amatoriale dai sedici ai ventitre anni. Così come Miles aveva omaggiato Jack Johnson, primo campione afroamericano, nell’omonimo disco, così io omaggiavo Battling Siki primo campione africano della storia della boxe in questo progetto per il festival. La cosa mi stimolava particolarmente perché feci un lavoro di ricerca importante prima di decidere l’argomento del progetto, poi grazie anche all’entusiasmo di Roberto che trovava la cosa interessante mi decisi a mettere nero su bianco il tutto. Incominciai a scrivere la musica sotto forma di “suite” in 6 movimenti, come i 6 rounds dell’incontro di Battling Siki contro Georges Carpentier che lo ha consacrato campione del mondo. Poi mentre leggevo un libro molto bello dedicato a lui, e scritto da un giornalista sportivo che si chiama Jean Marie Bretagne, durante un volo Parigi-Milano, sentii di voler scrivere un dialogo e dare voce al personaggio SIKI. Così con la massima spontaneità incominciai a scrivere senza occuparmi di punteggiatura, senso, forma, lasciando che le parole scaturissero da un flusso di pensieri ed emozioni. Il risultato é stato un dialogo immaginario fra il pugile ed il suo allenatore durante i minuti di riposo fra i rounds. Ho cercato di pensare all’umanità del personaggio ed al suo tormento interiore, provocato dal fatto che il suo allenatore si era venduto l’incontro e cercava di convincerlo ad andare giù… In effetti la leggenda racconta che il clan di Carpentier, un campione in declino, si mise d’accordo con il clan di Siki per convincerlo ad andare giù ad un round prestabilito. Ho cercato di restituire sul fondo di questo dialogo anche questa vicenda, intrecciandola ai movimenti musicali. |

|

|

|

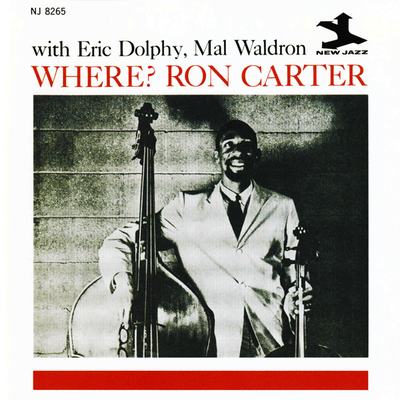

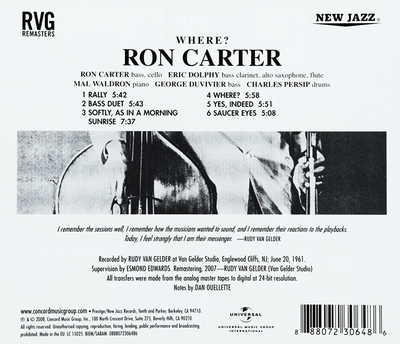

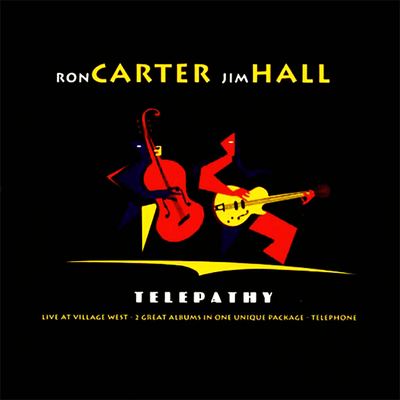

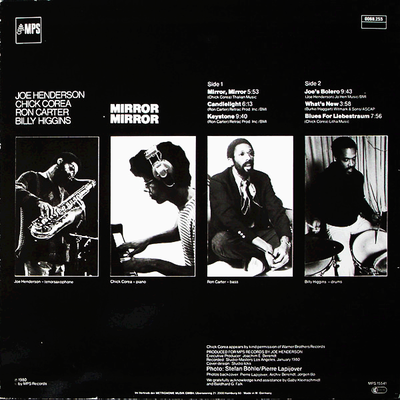

BMF: On your Facebook I read a really interesting debate which started from some cutting considerations which Ron Cater had told about some european double bass players (and Marc Johnson). You have analysed some of Ron’s works which were non properly well done… and this aspect leads me to ask you an opinion about the solo albums of some upright bassists who fall in the trap of electric bassists, by making some demonstration records, which looked like as calligraphic work as well as infinetly distant from those standards achieved through their collaborations… MG: As regards Ron Carter this is a specific issue, because according to what I’ve read and known, he has always shown a certain sense of superiority towards his white collegues and an obsessive passion for his own ego. Personally I’ve never loved those kind of records purely focused on the instrument, but there are some clear exceptions… I liked instead those musicians who were able to compose such a beautiful music and to use the traditional role of the bass and as a leader. Clearly there are here too some exceptions embodied by some great artists like Jaco, Stanley Clarke, John Patitucci, Skuli Sverrisson, Marc Johnson, Scott Colley, Anders Jormin, Gary Peacock and many others who could imprint their instrument the personality of the leader on the same terms as the instrument which were created specifically for that role. I think that Charlie Haden succeeded in this aspect, thanks to his peculiar voice as well as his recognizable individuality. The limit of Carter (including his solo albums) is to have preferred to try a dimension he was not so comfortable with instead of making room for his incredible skill as supporting musician and one-man band. And this is evident… |

BMF: Sul tuo facebook ho letto un’interessantissima disquisizione che partiva dalle aspre considerazioni che Ron Carter aveva espresso su alcuni contrabbassisti europei (e Marc Johnson). Hai preso in analisi alcuni lavori di Ron non propriamente riusciti… e questo mi spinge a chiederti un’opinione sui dischi solisti di alcuni contrabbassisti che cadono nella stessa trappola dei bassisti elettrici, con album dimostrativi, calligrafici e lontanissimi dagli standard raggiunti nelle loro collaborazioni… MG: Per Ron Carter la cosa è particolare, perché da quel che so e che ho letto, ha sempre dimostrato un certo disprezzo per i colleghi di strumento bianchi ed una maniacale passione per il proprio ego. Personalmente non ho mai amato i dischi dei bassisti o contrabbassisti incentrati esclusivamente sullo strumento, ma ci sono delle eccezioni... Mi sono piaciuti invece quei musicisti che hanno saputo comporre buona musica ed utilizzare il ruolo tradizionale dello strumento e quello in qualità di solista. Ovviamente ci sono delle eccezioni: grandi artisti come Jaco, Stanley Clarke, John Patitucci, Skuli Sverrisson, Marc Johnson, Scott Colley, Anders Jormin, Gary Peacock ed altri, hanno saputo dare allo strumento una personalità solistica allo stesso livello degli strumenti nati per quel ruolo. Penso che ci sia riuscito anche Charlie Haden con una sua voce tutta particolare, ed una personalità riconoscibile. Il limite di Carter e dei suoi dischi in solo, é che invece di dare spazio alla sua incredibile abilità di accompagnatore e uomo di orchestra, ha cercato di mettersi su di un terreno a lui poco congeniale. E questo si sente… |

|

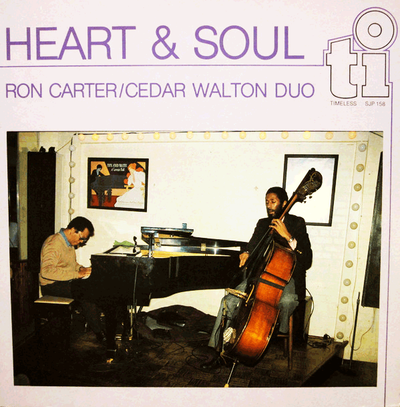

On the contrary, when he related to his collegues within a duo or a trio dimension, for instance, he was able to do the best of his art both as a solist and as a side man. For example I think about his records with Jim Hall or about the album Where on which there’s an amazing bass duet together with George Duvivier, or the works with Joe Henderson Trio and also his duo with Cedar Walton and many others… Here, we should be honest and try to give the best but without overdoing it or deviating from more familiar path. When I listen to Ron Carter’s Plays Bach album I just feel uncomfortable for him… Instead I deeply love those artists who could combine a compositional brilliance with the ability to integrate double bass into the tangles of arrangements without any demonstrative intent, but by preserving its nature, voice as well as its melancholy timbre. |

Al contrario, quando si confrontava con altri strumentisti in duo o trio per esempio, riusciva a dare il meglio della sua arte sia come solista che come accompagnatore. Penso per esempio ai suoi dischi con Jim Hall, o al disco Where dove c’é un bellissimo bass duet dove duetta con George Duvivier, o ai dischi con Joe Henderson in trio, o il duo con Cedar Walton ed altri... Ecco, bisognerebbe essere sinceri e cercare di dare il meglio di sé senza strafare o invadere terreni non proprio congeniali. Quando ascolto il disco di Ron Carter dedicato alle suites di Bach mi sento a disagio per lui... Invece amo profondamente coloro che sono riusciti a coniugare una sapienza compositiva inserendo il contrabbasso nelle maglie degli arrangiamenti senza inutili effetti dimostrativi, preservandone il carattere, la voce, ed il malinconico timbro. |

|

BMF: France is the land of the greatest double bass players who can refer to a valuable school particularly focused on free and improv. Who are your favorite artists? And I just cannot bu ask you something about Jean-François Jenny-Clark who’s my musical totem… MG: There is undoubtedly a free jazz school which has moved its steps since the end of ’20 but I don’t know precisely the figures of that historical period. In 1917 when Unitest States took part in The Great War, many american bands settled in France in order to play in cabarets of Pigalle and Rive Gauche. This may have contributed to inspire an interest and an important impulse so as to create a generation of French jazz musicians; then with the advent of Hot Club de France they invented a unique style thanks to Stephane Grappelli and Django Reinhardt. Later in the ‘40s thanks to Pierre Michelot (Bud Powell’s double bass player) the art of double bass in France developed a bop trend and this was also thanks to the presence of a great drummer like Kenny Clarke. I like so much Jean Jacques Avenel, Bruno Chevillon, Jean Paul Celea, Henri Texier, Jean Philippe Viret, Luigi Trussardi, Gilles Naturel, Michel Zenino, Claude Tchamitchian, Thomas Bramerie and of course Jean François Jenny Clark. Unfortunately I didn't get a chance to meet or see him live. When I won the competition at the Conservatoire National Superior de Musique de Paris, he was still chair of double bass department. Then at the beginning of the academic year he arranged to be replaced by Riccardo Del Fra so as to heal from a serious illness. But unfortunately he passed away … my collegues of Conservatory who had the fortune to study with him the year before, told me about his extraordinary humanity and competence in music. Stephane Kerecki for instance has studied with him for two years and I find that he’s one of his direct successor. |

BMF: La Francia è terra di grandi contrabbassisti, con una ragguardevole scuola particolarmente improntata al free e all’improvvisazione. Quali sono i tuoi prediletti? E non posso astenermi dal chiederti qualcosa su Jean-François Jenny-Clark che è un mio totem musicale… MG: C’é indubbiamente una scuola jazz francese che muove i suoi passi già dalla fine dagli anni ‘20 ma non conosco bene i nomi di quel periodo storico. Nel 1917 con la partecipazione degli Stati Uniti alla Grande Guerra molte orchestre americane si stabilirono in Francia per suonare nei vari cabaret di Pigalle e della Rive Gauche. Questo deve aver contribuito a creare un interesse ed un impulso importante per creare una generazione di musicisti di jazz francesi, poi con l’avvento dell’Hot Club de France si creò uno stile anche unico con Stephane Grappelli e Django Reinhardt. Negli anni ‘40 poi grazie a Pierre Michelot (contrabbassista di Bud Powell) il “contrabbassismo” francese ebbe un suo impulso importante verso il bop, ed anche la grazie alla presenza del grandissimo batterista Kenny Clarke. Mi piacciono tantissimo Jean Jacques Avenel, Bruno Chevillon, Jean Paul Celea, Henri Texier, Jean Philippe Viret, Luigi Trussardi, Gilles Naturel, Michel Zenino, Claude Tchamitchian, Thomas Bramerie e naturalmente Jean-François Jenny-Clark, che purtroppo non ho avuto l’occasione di incontrare o di vedere dal vivo. Quando ho vinto il concorso al "Conservatoire National Superior de Musique de Paris” lui era ancora il titolare della classe di contrabbasso. Poi all’inizio dell’anno scolastico si é fatto sostituire da Riccardo Del Fra per potersi curare da una grave malattia, ma purtroppo non ce l’ha fatta. I miei compagni di conservatorio che avevano studiato con lui l’anno prima mi hanno poi raccontato della sua straordinaria umanità e della sua competenza artistica. Stephane Kerecki, per esempio ha studiato con lui due anni e trovo sia uno dei suoi più diretti eredi. |

|

I adored Jean Jacques Avenel whom I met so many times and I saw him in concert dozens of times both along with Lacy and also his own bands. I’ve been fortunate to replace him in Achille Gajo Trio with John Betsch on drums, which was for me an amazing experience just by playing with them, and later just by listening to JJ who played Achille’s music which I knew so well, and I learnt so many things just by relating with a great artist like him. At the “Sept Lezard”, a club in Marais that doesn’t exist anymore, JJ was used to performe with his African group in which he was also used to play the kora and often also with Steve Potts band. |

Ho adorato Jean Jacques Avenel che ho incontrato tante volte, ed ascoltato decine di volte in concerto, sia con Lacy che con i suoi gruppi. Avevo la fortuna di sostituirlo nel trio di Achille Gajo con John Betsch alla batteria, fu per me una esperienza favolosa già di suonare con loro, ma poi anche di ascoltare JJ suonare la musica di Achille, che conoscevo bene, ed imparare tante cose confrontandomi con un grande come lui. Al “Sept Lezard”, un club del Marais che non esiste più, JJ si esibiva spesso con il suo gruppo africano nel quale suonava anche la kora, e poi spesso con il gruppo di Steve Potts. |

|

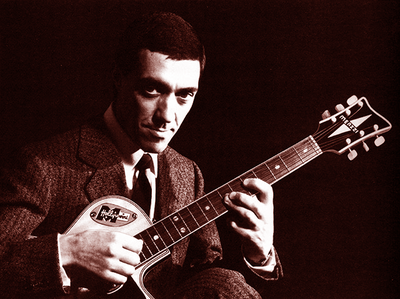

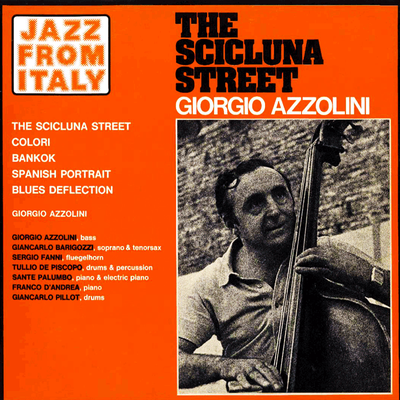

BMF: I’d like to also mention with you the italian scene which has been an important hotbed for double bass players since time immemorial at different levels, from Giorgio Azzolini and even before… Which was in your opinion the path of double bass in our country? MG: Italy has always been the hotbed for extraordinary upright bassists in every age, and even currently, there are new interesting generations which prove that the italian school is actually second to none. Regardless of roles and musics we can boast the excellence of different european even global talents. In Italy I believe that we should get everythings started from ‘30s maybe with Michele D’Elia (my fellow citizen), Gorni Kramer, Carlo Loffredo, Franco Cerri, poi Marco Ratti, Giorgio Azzolini, Giovanni Tommaso, Giorgio Rosciglione, etc. Unlike the Parisian scene where American musicians lived on a permanent basis since 1917, it seems that in Italy they related to “passing” american artists and they learned a lot from the few records which arrived despite the difficulties; so much that Enrico Rava told us for instance that they arranged some masonic private clubs where some chosen few could secretly listen to jazz music by sharing records that anyone took with him. In any case a distinctive list of good double bass players originated from the encounters with the americans who came in Italy. I think, for instance, that some of the best artists studied under the tutelage of Chet Baker who during two phases of his life had lived in Italy on a permanent basis. I think about Riccardo Del Fra, Furio Di Castri and many others… |

BMF: Mi piacerebbe anche, con te, non dimenticare l’Italia, che da sempre sforna una scuola contrabbassistica di valore, nelle sue diverse accezioni. A partire da Giorgio Azzolini e anche prima… quale pensi sia stato il “cammino” del contrabbasso nel nostro paese? MG: L’Italia ha sfornato sempre contrabbassisti straordinari in ogni epoca, ed anche attualmente ci sono nuove generazioni interessanti che dimostrano che la scuola italiana non é affatto seconda a nessuno, anzi. Indipendentemente dai ruoli e dalle musiche possiamo vantare tanti talenti di livello europeo se non mondiale.. In Italia credo che si debba far partire tutto dagli anni ‘30 forse con Michele D’Elia (mio conterraneo), Gorni Kramer, Carlo Loffredo, Franco Cerri, poi Marco Ratti, Giorgio Azzolini, Giovanni Tommaso, Giorgio Rosciglione, etc. Diversamente dalla scena parigina, dove gli americani vivevano stabilmente già dal 1917, sembra che in Italia a quanto pare ci si confrontava con gli americani “di passaggio” e si imparava tanto dai dischi – pochi - che arrivavano nonostante le difficoltà. Tant’é che come racconta Enrico Rava per esempio, si creavano circoli privati “carbonari” dove si ascoltava la musica jazz di nascosto condividendo i dischi che ogni membro portava. In ogni caso fior di contrabbassisti son venuti fuori dagli incontri con gli americani che venivano in Italia. Penso per esempio che alcuni dei migliori si sono formati sotto l’ala di Chet Baker che per due periodi di tempo ha abitato in Italia stabilmente. Come Riccardo Del Fra, Furio Di Castri ed altri… |

|

BMF: Let’s talk about the emancipation of double bass. After the earthquakes caused by some brilliant personalities like Jimmy Blanton and Scott LaFaro, could the language of the instrument develop further? Have we arrived at NHØP’s omen that is to say: “(double bass) has become an expressive instrument like all the others”? I’d like to ask you the same thing about electric bass after the tsunami caused by Jaco Pastorius. After years and years of shameless imitations of Jaco and Marcus Miller, who could be considered as an authentic innovator? MG: The solo dimension of the instrument has had an extraordinary margin for development over the last 50 years. There are fabulous and culted musicians – exactly in tune and very fast – characterized by an excellent skill and they are also interesting to listen to. I must say anyway that - with rispect to the expression - there has been a regression mostly in jazz over the last 10 years and not because of the “senior” musicians… It’s more and more rare to listen to records where double bass plays an equal role as the other instruments. And I see the instrument increasingly included in a traditional trend which itself tried to avoid over time, most of all in US productions which – like it or not – influence the trends of the moment. I listen to more and more musicians who play without dynamics and with little expressivity, by respecting the role of the instrument like it was in the ‘50s and by hiding behind a false notion of “truth” like if they tell you that jazz must be played just with catgut strings and without amplification. This is the kind of absolute truth that, in my opinion mostly in jazz doesn’t exist. It may be a transitional phase but I find all of that manneristic and not very interesting, particularly when it comes out from 30 years old guys who should be instead in a creative, dynamic and open phase. And the “seniors” in this case prove again to be avant-garde at the moment in many aspects. But there are clearly some exceptions: for instance I like very much Matt Brewer who as regards melodic and rythmic approach plays really interesting stuff even if - like many others - he has chosen an old-fashioned sound which partially forces to play over a quite limited dynamic range. |

BMF: Parliamo di emancipazione del contrabbasso. Dopo i terremoti suscitati da geni come Jimmy Blanton e Scott LaFaro il linguaggio dello strumento è secondo te in ulteriore evoluzione? Siamo arrivati a quello che NHØP presagiva, cioè che “è diventato uno strumento espressivo come gli altri”? Vorrei farti la stessa domanda riguardo al basso elettrico dopo lo tsunami Jaco Pastorius. Dopo anni e anni di clonazioni e di spudorate imitazioni di Jaco e di Marcus Miller, chi può essere considerato un autentico innovatore? MG: Indubbiamente il solismo sullo strumento ha avuto dei margini di evoluzione straordinari negli ultimi 50 anni. Ci sono strumentisti favolosi e colti, intonatissimi e veloci, con delle ottime tecniche, ed anche interessanti da ascoltare. Devo dire che però - espressivamente parlando - trovo che ci sia stata una involuzione soprattutto nel jazz degli ultimi 10 anni, e non per colpa dei “vecchi”... Ascolto sempre meno dischi dove il contrabbasso ha un ruolo paritario rispetto agli altri strumenti. E vedo sempre più lo strumento rientrare nei ranghi di una tradizione alla quale stava con il tempo cercando di sfuggire, soprattutto nelle produzioni statunitensi, che volente o nolente influenzano le mode del momento. Sento sempre più gente suonare senza dinamiche, e con poca espressività, rispettando il ruolo dello strumento come però poteva essere negli anni ‘50, e trincerandosi dietro una falsa nozione di “verità”, come quando ti dicono che il jazz si suona solo con le corde di budello e senza amplificazione. Ecco la nozione di verità assoluta, che secondo me, soprattutto nel jazz non esiste. Sarà forse una fase di passaggio, ma trovo tutto ciò manieristico e molto poco interessante, specie quando viene da alcuni ragazzi di trent’anni che dovrebbero essere invece in una fase creativa, dinamica ed aperta. Ed i “vecchi” in questo caso si dimostrano per il momento ancora “avanguardisti” in molte cose. Ma ci sono ovviamente eccezioni, per esempio mi piace moltissimo Matt Brewer, che melodicamente e ritmicamente suona cose molto interessanti, anche se come molti, ha scelto un suono "all'antica” che in parte costringe a suonare su di un range dinamico abbastanza limitato. |

|

As concerns electric bass I think that is happening almost the same thing but with some variations. When I read on forums the same boring things like “the true bass is only the 4-strings Fender Precision”, I tell myself that there are so many people who have an embedded limiter in their brain as well as in their ears and they want to force it on the other people, too. Unfortunately also in this case the manierism compells many people to comply with the temporary fashion often by degenerating themselves in order to find the approval or simply to work. Anyway when I listen to Skùli Sverrisson, Thundercat, Michael Manring, Cody Wright, Victor Wooten and others I tell myself that there are still people who are pushing the instrument beyond the limits. And this is good. |

Per quanto riguarda il basso elettrico sta accadendo in parte la stessa cosa, con le dovute differenze. Quando leggo sui forum i pipponi sul fatto “che il basso é solo il Fender Precision a 4 corde” mi dico che c’é tanta gente che ha il “limiter” incorporato nel cervello e nelle orecchie, e lo vuole imporre agli altri. Purtroppo anche in questo caso il manierismo costringe tanti ad adeguarsi alla moda del momento spesso snaturando se stessi per cercare consenso e per lavorare. Eppure quando sento Skùli Sverrisson, Thundercat, Michael Manring, Cody Wright, Victor Wooten, ed altri, mi dico che c’é ancora gente che sta spingendo lo strumento ad andare oltre. E questo è un bene. |

|

BMF: The world of jazz is really full of double bass players who have been maybe underrated. I think about some artists like Chuck Domanico, Albert Stinson, Bob Magnusson, Ron Mathewson, Mike Richmond, Jeff Clyne and many others.. How can you explain this distraction shown also by the insiders? MG: Many of the mentioned artists were often brilliant studio musicians who for one reason or another didn’t transcend their role; like Domanico for instance who had a permanent place in the television or movie productions, and he was also in Los Angeles, so he was out of the jazz scenes. Richmond on the contrary has taught for many years at NY University and he slowed down his concert and discographic activities for this reason, as Magnusson did. Other artists simply didn’t have a chance like Stinson or they were not in the right situations. The invisibility has often a geographical explanation like the Scottish Mathewson. I think for instance about the villain indifference shown by the American productions and media towards some European musicians who gave so much over their 70 years of jazz. For many of them Europe shall remain as a “a province of the realm” and this is not fair both as regards a business and an artistic profile. |

BMF: Il mondo del jazz è davvero pieno di contrabbassisti che non sono stati forse opportunamente considerati. Penso a gente come Chuck Domanico, Albert Stinson, Bob Magnusson, Ron Mathewson, Mike Richmond, Jeff Clyne e tanti altri… come spiegheresti questa disattenzione perpetrata stesso dagli addetti ai lavori? MG: Spesso molti di loro erano dei musicisti di studio straordinari che per una ragione o per l’altra non sono andati oltre quel ruolo come Domanico per esempio che aveva un posto fisso nelle produzioni televisive o per il cinema, e poi era a Los Angeles, quindi fuori dai circuiti jazzistici. Richmond invece insegna da tanti anni nella NY University, ed ha rallentato l’attività concertistica e discografica per questo motivo, come Magnusson del resto. Altri invece semplicemente non hanno avuto fortuna come Stinson o non si sono ritrovati nelle giuste situazioni. Spesso l’invisibilità ha anche una ragione geografica come Mathewson (che é scozzese). Penso per esempio al criminale disinteresse delle produzioni e dei media americani sugli straordinari musicisti europei che in 70anni di jazz hanno dato tantissimo per questa musica. Per tanti di loro l’Europa rimane “provincia del regno” e questo non é giusto sia dal punto di vista del business che da quello artistico. |

|

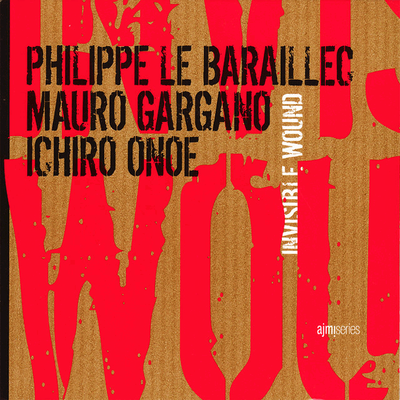

BMF: Among your collaborations there are two records of a trio with the pianist Philippe Le Baraillec and the drummer Ichiro Onoe whom I consider as really amazing and elegant artists. Would you like to talk about that experience? The interplay was very considerable… Could that Trio be repeated? MG: It was a beautiful musical moment. I joint the Trio thanks to Bruno Angelini who had recommended Philippe, me and Ichiro, for his own new release right before we started to record. We reached the interplay immediately and we even had much room for the improvisation and for the proposal of our personal interpretations. Everything was natural in recording studio and also thanks to the extraordinary sound of “Buissonne” and Gerard De Haro, we were able to catalyze a certain degree of emotions. Philippe was so happy that when the record was released he wrote our names alongside his own as if were an equal trio despite the fact that all the compositions were all written by himself. |

BMF: Tra le tue collaborazioni, ci sono due dischi in trio con il pianista Philippe Le Baraillec e il batterista Ichiro Onoe, che considero davvero splendidi e di grande eleganza. Ci vuoi parlare di quell’esperienza? L’interplay era notevolissimo… potrebbe riproporsi quel trio? MG: È stato un bellissimo momento musicale. Sono entrato nel trio grazie a Bruno Angelini che aveva consigliato a Philippe me e Ichiro poco prima di registrare il suo nuovo disco. L’intesa si è creata immediatamente, ed addirittura abbiamo avuto molto spazio per l’improvvisazione e per proporre soluzioni musicali personali. In studio tutto è stato abbastanza naturale, e grazie anche al suono straordinario della “Buissonne” e di Gerard de Haro siamo riusciti a catalizzare una certa dose di emozione. Philippe era talmente contento che quando il disco é stato pubblicato ha messo i nostri nomi accanto al suo come se fosse un trio paritario, in realtà le composizioni erano tutte sue. |

|

Then Philippe went through a difficult phase because he began to have some problems with the producer of AJMI records and the new album was getting less possible. The producer Jean Jacques Pussiau came to his aid by proposing to him to record in trio together with Scott Colley and Bill Stewart. At first Philippe was reluctant but I encouraged him to make it possible because that was a chance too good to miss: it’s not everyday you receive a proposal to record an album together with those excellent artists. Anyway there was no money for making the album so we went back to the original idea and at least we would have invited a guest artist like Chris Cheek. The album was recorded six months after but it was a really frustrating session for me. Something went wrong in our harmony maybe in the aftermath of production’s problems, probably because the producer wanted to take part to the artistic direction or maybe because Philippe expected too much and had too responsabilities… In any case Philippe was very nervous and disinclined to have a personal as well as artistical exchange with us. That recording session was surely one of the most frustrating experience I’ve ever lived in my life. On the one hand Chris Cheek was adorable and inspired as never before, Ichiro was positive and comunicative while Philippe kept to himself and to his piano. He focused only on his prformance and avoided any dialogue or suggest which we or even the producer proposed. I remember of a song which was recorded ten times just to make him sutisfied with his solo while Chris Cheek’s lip was bleeding and Ichiro sighed behind his drums. It was therefore the last time I saw him and it was such a pity because we should have supported that interplay, we should have developed and protected it from negative influences, ego and business. |

Poi c’é stato un periodo abbastanza oscuro nel quale Philippe aveva problemi con il produttore della AJMI, ed il nuovo disco diventava più lontano. In suo aiuto venne il produttore Jean Jacques Pussiau che però gli propose di registrare in trio con Scott Colley e Bill Stewart. Philippe inizialmente era restio, ma lo incoraggiai a farlo perché sono occasioni da non perdere, non capita tutti i giorni di avere una proposta per registrare un disco con due nomi di questo livello. Però poi in realtà i soldi per realizzare il disco non c’erano più, e quindi si tornò all’idea iniziale di registrare insieme in trio ed al limite invitare un ospite come Chris Cheek. Il disco fu registrato sei mesi dopo ma fu una sessione molto frustrante per me. Qualcosa si era rotto nella nostra intesa forse a seguito dei problemi di produzione, forse perché il produttore voleva partecipare alla direzione artistica, o forse perché Philippe si era caricato di troppe aspettative e responsabilità… In ogni caso Philippe appariva molto nervoso, e poco incline a scambiare con noi sia sul piano umano che musicale. Quella registrazione fu sicuramente una delle più frustranti che abbia fatto in vita mia. Da una parte Chris Cheek era adorabile e ispirato come non mai, Ichiro era positivo e comunicativo, mentre Philippe si era chiuso in sé stesso e nel suo pianoforte. Concentrato al massimo solo su di sé e sulla sua performance, non solo evitava qualsiasi confronto o consiglio che partisse da noi, ma anche dal suo produttore. Ricordo di un brano che fu registrato 10 volte solo perché lui fosse contento del suo solo, mentre Chris Cheek sanguinava dal labbro e Ichiro sospirava stanco dietro la sua batteria. Insomma, fu l’ultima volta che lo vidi e fu un vero peccato perché quella intesa che si era creata andava sostenuta, coltivata e protetta dalle energie negative, dall’ego, e dal business. |

|

|

|

BMF: Among the others you have also played with René Urtreger… what do you remember about that collaboration? MG: René is one of the most important jazz figure in France, he keeps playing, making projects and on balance he enjoys playing what he likes. I met him thanks to Nicolas Folmer who was commissioned to start a band for René. When we met at first he encouraged me from the initial notes. At the end of the first concert – talking about me - he told Nicolas pointing me with his finger: «If we have had more people like him during the second world war, we would have won the Germans in a few days!» Which was the typical spirit of René, a person characterized by such a great intelligence, sense of humour and self-mockery like few others. As when during the festival “Django D’Or” he was found on the sofa of the backstage lying down by the journalist who had to interview him, the same man who ran from the room screaming: «HE’S DEAD!», René came out laughing like crazy… He told me some incredible stories and experiences of the past, as the ones with Mile Davies and the greatest artists with whom he shared the stage. And musically he’s always ready to teach you something new. We recorded for his own 75 years one live cd at the Duc des Lombards, one live Dvd at the Petit Journal Montparnasse. Lately we have played in trio together with his historical drummer Eric Dervieu and we had so much fun playing some standards. He proposed to me to join a new sextet of his own, we’ll see.. |

BMF: Tra i tanti, hai suonato anche con René Urtreger… che ricordi hai di quella collaborazione? MG: René é una delle personalità jazzistiche più importanti in Francia, continua a suonare a fare progetti e tutto sommato a divertirsi suonando quello che gli piace. L’ho incontrato grazie a Nicolas Folmer il quale era stato incaricato di formare una nuova band per René. Quando ci siamo incontrati mi ha subito incoraggiato dalle prime note. Alla fine del primo concerto riferendosi a me disse a Nicolas indicandomi con il dito: «Se durante la seconda guerra mondiale avessimo avuto più persone come questo qui avremmo sconfitto i tedeschi in qualche giorno!» Il classico umorismo di René, persona dotata di una intelligenza, di un senso dell’humour e dell’autoderisione come pochi. Come quando durante il festival “Django D’Or” si fece trovare steso come un morto sul divano del camerino dal giornalista che doveva intervistarlo che corse fuori gridando: “É MORTO!!!” Venne fuori ridendo come pazzo… Ha condiviso con me aneddoti ed esperienze del passato incredibili, come le storie con Miles Davis, ed i grandi con cui ha condiviso il palco. E musicalmente é sempre pronto ad insegnarti qualcosa di nuovo. Abbiamo registrato per i suoi 75 anni un cd live al Duc des Lombards, un dvd live al Petit Journal Montparnasse. Ultimamente abbiamo suonato in trio con il suo batterista storico Eric Dervieu, e ci siamo divertiti tantissimo suonando standards. Mi ha proposto di suonare con un suo nuovo sestetto, vedremo. |

|

BMF: You play mainly double bass but what’s your relationship with the electric bass? Would you like to talk about your gear? MG: I gave up electric bass since 1998 to switch to double bass that took more time and study both for the classic repertoire and for jazz, too. Then it began to bother me having to insert the jack to the amplificator… Musically I didn’t get to play on electric bass except for rare occasions. Recently I started to play it for pleasure alone in my house, maybe I wil take a six strings in the near future. I got three double basses, two of them are in France and one in Italy. My main instrument is a french double bass of Patrick Charton, C21 n°1, which is really innovative with a removable neck and a lower boat made of different materials, adjustable bridge, mobile nut and alterable in scale. I was the first one to own this model and I’ve been glad to have contributed to its development. Despite all those techological innovations which could make it sound mainly focused on the contemporary music, the instrument is really versatile and it adapts itself both to the amplified and acoustic sound with a valuable projection of vibrations. My second double bass is a recent acquisition, it’s a Thibouville Lamy of 1880 and I’m searching for an appropriate site up for it. Then in Italy I have a double bass made in German in the ‘60s, a customed ex-DDR with a wooden soundboard and a low boat made of plywood which I use as a simply mule. I got two electric bass: one standard 5-strings Fender Jazz bass of 1996 and a 4-strings Squier Jaguar bass. As amp I own a little 400watt Acoustic-Image. |

BMF: Suoni prevalentemente il contrabbasso, ma che rapporto hai oggi con lo strumento elettrico? Ci parli della tua strumentazione? MG: Dal 1998 ho accantonato il basso elettrico per il contrabbasso. Il contrabbasso mi richiedeva più tempo e studio sia per il repertorio classico che per il jazz. Poi incominciava a darmi fastidio il fatto di dover attaccare il jack all’amplificatore... Musicalmente non ho avuto occasione di utilizzare l’elettrico salvo che in rare occasioni. Ultimamente ho ricominciato a praticarlo per puro diletto da solo in casa, forse mi prenderò un 6 corde prossimamente. Possiedo tre contrabbassi, di cui due sono in Francia ed uno in Italia. Come strumento principale ho un contrabbasso francese di Patrick Charton, C21 n°1, uno strumento innovativo con manico smontabile e fondo in materiale composito, anima regolabile, capotasto mobile regolabile in altezza. Sono stato il primo a possedere questo prototipo e sono stato contento di aver contribuito alla sua evoluzione. Nonostante tutte queste innovazioni tecnologiche che possono farlo sembrare votato esclusivamente al contemporaneo, si tratta di uno strumento versatilissimo e si adatta molto al suono sia amplificato che acustico, con una proiezione di suono notevole. Il mio secondo contrabbasso é di recente acquisizione, é un Thibouville Lamy del 1880, al quale sto cercando un set up adeguato. Poi in Italia ho un contrabbasso di fattura tedesca degli anni 60, uno strumento di fabbrica ex-DDR con tavola in legno e fondo in compensato che uso come muletto. Possiedo due bassi elettrici: 1 fender Jazzbass 5 corde standard del 1996, e uno Squier Jaguar bass a 4 corde. Come Ampli possiedo un piccolo Acoustic-Image da 400watt. |

|

BMF: Regardless of numbers or genres, I want to ask you who are for you the double bass players nowadays and whom you feel closer to as concerns your compositional and musical approach… MG: In my personal Olympo there are a lot of different musicians and styles but which for me are an infinite source of inspiration: Stefano Scodanibbio, Charlie Haden, Marc Johnson, Gary Peacock, Scott Colley, Bruno Chevillon, Furio di Castri, Paul Chambers, Jean Jacques Avenel, Mingus, Anders Jormin, Christian McBride, Palle Danielsson, Ben Allison, Larry Grenadier, John Ore, Wilbur Ware, François Rabbath… |

BMF: Senza limite di numero e di stili, voglio chiederti quali sono oggi i contrabbassisti che ti piacciono di più e che senti più affini al tuo modo di comporre e suonare… MG: Nel mio Olimpo ci sono molti musicisti e di stili effettivamente diversi ma che per me sono una fonte inesauribile di ispirazione: Stefano Scodanibbio, Charlie Haden, Marc Johnson, Gary Peacock, Scott Colley, Bruno Chevillon, Furio di Castri, Paul Chambers, Jean Jacques Avenel, Mingus, Anders Jormin, Christian McBride, Palle Danielsson, Ben Allison, Larry Grenadier, John Ore, Wilbur Ware, François Rabbath... |

|

BMF: If you had to compile an instinctive list of “desert island records” what would you think of? MG: My ideal list begins and ends with an “etc” because they are a lot… |

BMF: E sempre senza limiti di sorta, se tu dovessi stilare una lista istintiva di “dischi da isola deserta” quali ti verrebbero in mente ora? La mia lista comincia e poi finisce con un “etcetera” perché sono tantissimi… |

Fauré “Requiem”, Charlie Haden “Nocturne”, “Liberation Music Orchestra”, “Silence”, “Folk Songs", Scriabin “Sonate”, Keith Jarrett “My Song”, Pat Metheny “First Circle”, “New Chautaqua", “80-81”, Mingus “Ah-Hum”, Egberto Gismonti “Sanfona”, Miles Davis “Kind of Blue”, “Working”, “ESP”, “Tutu", “Greg Osby “Invisible Hand”, Paul Bley “Partners”, John Coltrane “My Favorite Things”, Enrico Pieranunzi “Raccondi Mediterranei”, Duke Ellington “At Newport”, “Far-East suite”, “Stefano Scodanibbio “Voyage that never ends”, “Bill Evans “You Must believe in spring”, Kenny Wheeler “Der Wan”, “Angel Song”, Joshua Redman “Moodswing”, Marc Johnson “Bass desires”, Brad Mehldau “Places”, Luigi Tessarollo “Colori”, Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli “Chopin” etc..

|

BMF: I cannot but ask you an opinion about the many pop music interpretations of jazz musicians. The argument supported by those in favour of these operations is that jazz becomes more accessible for the people. Others consider this “bad habit” as a sort of disaster which risks compromising the purity of jazz. Whaat’s your attitude to such a divisive issue? MG: This is a long-standing debate which lasts from the 1970s… I believe that for a jazz musician the matter shouldn’t be the kind of music but the style of his own approach. You can play pop, rock, classic jazz, electro and if you play it improvising in the spirit of jazz everything’s fine. Personally what bothers me is simply the compositional, interpretative and manneristic inflexibility which impedes improvisation. André Hodeir theorized that anyone could play a “perfect form” of jazz without improvisation. Or rather anyone could do it by writing all the solos so as to prevent (in his opinion) all the possible “mistakes” or “wrong interpretations”… This is in my vew all that kills the Jazz that is to say its lifeblood and its spirit. If you remove the spontaneity from Jazz it will turn to “classic” music. This is just an example but that could be seen as a guiding principle by those musicians who are intent on killing Jazz so its capacity to regenerate itself thanks to improvisation regardless of pop or traditional contexts. Another matter is the attitude of the record labels which - taking account of proper exceptions – are at the end of their rope by now. So they currently aim to the immediate outcome and jazz-pop projects fall within this scheme. The business has its rules and many people comply with its diktats. |

BMF: Non posso esimermi dal chiederti un’opinione circa le svariate iniziative di rivisitazioni pop da parte dei musicisti jazz. L’argomento che portano avanti i favorevoli a queste operazioni è che così il jazz diventa più fruibile da parte delle masse. Altri considerano invece questo “vizio” come una sciagura che finisce per sporcare la purezza del jazz. Come ti poni rispetto a questo tema così divisivo? MG: É una diatriba annosa che dura dagli anni ‘70… Io credo che per un jazzista non sia lo stile di musica il problema, ma la maniera. Si può suonare pop, rock, jazz tradizionale, electro, ma se viene suonato improvvisando con lo spirito del jazz tutto va bene. A me personalmente infastidiscono solamente le rigidità compositive, interpretative o manieristiche che impediscono l’improvvisazione. André Hodeir teorizzò che si potesse suonare una “forma perfetta” di jazz senza le improvvisazioni. O meglio, scrivendo tutti i soli ai vari solisti così da evitare, secondo lui, “errori” o “interpretazioni sbagliate”… Ecco, tutto ciò secondo me uccide il jazz e gli toglie linfa ed anima. Se togli spontaneità al jazz diventa una musica “classica”. Questo é un esempio che però potrebbe essere preso a modello per tutta una serie di musicisti che uccidono il jazz quindi la capacità di rigenerarsi nell’improvvisazione che sia nel pop o anche nella tradizione. Un altro problema é quello che in realtà vogliono le case di produzione, che oramai per la maggior parte, con le dovute eccezioni, sono attaccate alla canna del gas. Quindi puntano attualmente solo su ciò che rapporta sicuramente, ed i progetti jazz-pop rientrano in questo schema. Il business ha le sue regole, e molti si piegano ai suoi diktat. |

|

|

|

Clicca qui per modificare.