INTERVIEW WITH

NEIL STUBENHAUS

|

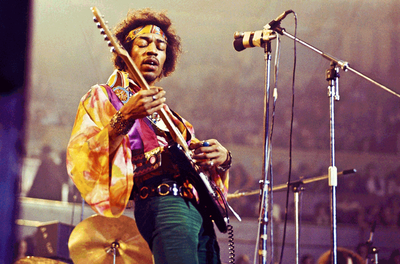

«Let’s face it, Jaco changed the world of bass. He changed it for me in a big way. I should also credit him for helping to make me confident enough to leave my upright in the closet. He was a friend and I cherished that lucky friendship. A Jaco, a Hendrix, a Brecker comes along once in a lifetime. I can't predict if there is more evolution to come, but anything can happen. Expression is individual, and in the ear of the beholder»

............................. «Diciamoci la verità, Jaco ha rivoluzionato l’universo del basso. Lo ha cambiato in un modo grandioso per me. Dovrei inoltre ringraziarlo per avermi aiutato a prenderci confidenza a tal punto da lasciare il mio contrabbasso nell’armadio. Era un amico ed ho apprezzato quella fortunata amicizia. Un Jaco, un Hendrix, un Brecker capitano una volta nella vita. Non posso predire se ci sia ancora un margine di evoluzione, ma tutto può succedere. L’espressione è individuale, e nell’orecchio di chi assiste» |

|

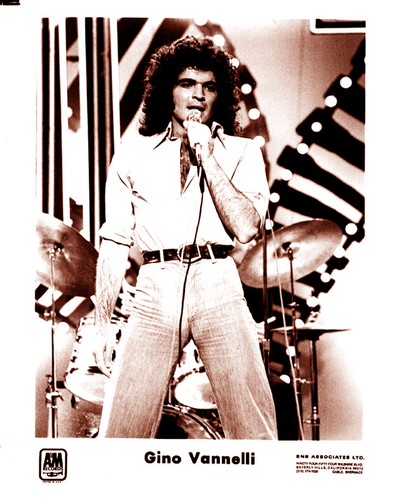

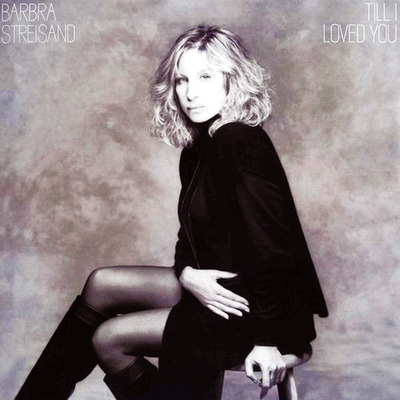

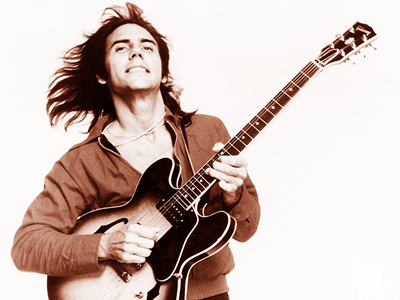

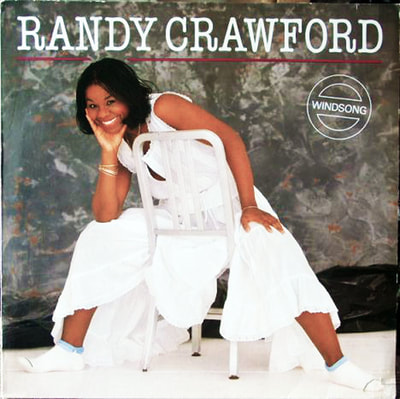

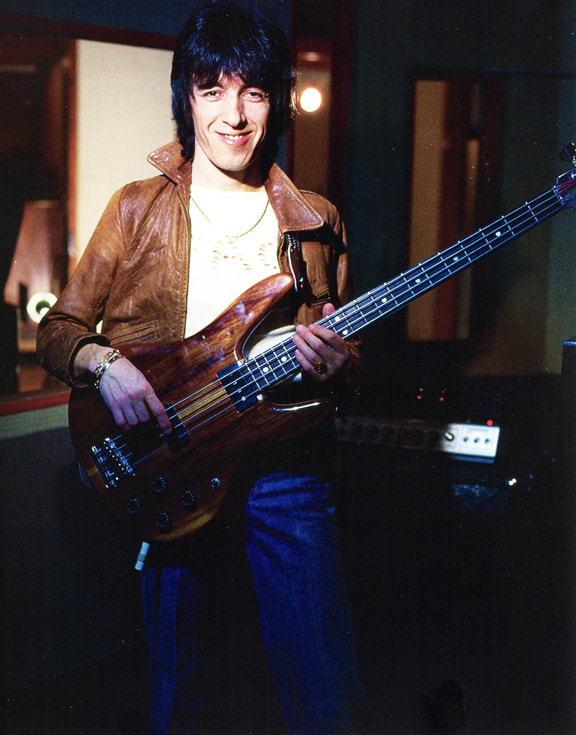

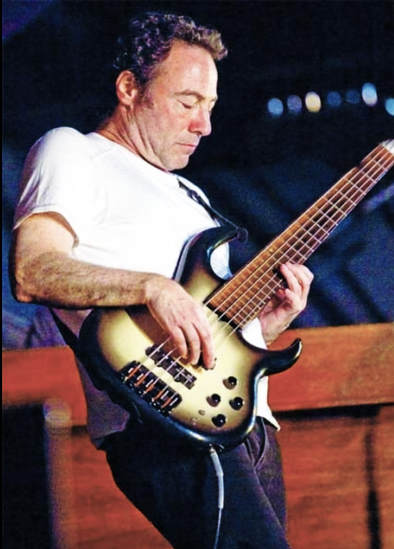

All of us, anyone who loves music, could find in his/her house at least a couple of records with Neil Stubenhaus on bass. Neil belongs to that precious and limited group of dreamy session men and musicians whom any artist would like to recruit. The fact that the role of bass is played by Neil Stubenhaus has meant - for over thirty years – that you could count on the talent, the empathic sound and the discreet virtuosism of a creative performer of his own instrument. Neil Stubenhaus has played on something like a thousand albums, collaborating with some great stars like Quincy Jones, Gino Vannelli, Blood, Sweat&Tears, Tom Scott, Barbra Streisand, Larry Carlton, George Benson, Steve Cropper, Randy Crawford, Al Jarreau, Commodores, Julio Iglesias, The Isley Brothers, Dionne Warwick, Ute Lemper, Smokey Robinson, Natalie Cole, Burt Bacharach…The list is far from being complete. He’s able to enhance music proposals that are close to Adult Oriented Rock as well as to soul; he’s refined and essential in fusion context, accurate and implacable in rock music. |

Ognuno di noi, chiunque ami la musica, avrà in casa almeno un paio di dischi con Neil Stubenhaus al basso. Come minimo. Neil fa parte di quella preziosa e ristretta casta di session men da sogno che qualunque artista vorrebbe ingaggiare. Assicurarsi che la sedia del bassista sia occupata da Neil Stubenhaus significa, da più di un trentennio, poter contare sul talento, sull’empatia sonora e sul virtuosismo discreto di un grande interprete del suo strumento. Neil Stubenhaus ha suonato in qualcosa come mille album, collaborando con grandi stelle come Quincy Jones, Gino Vannelli, Blood, Sweat&Tears, Tom Scott, Barbra Streisand, Larry Carlton, George Benson, Steve Cropper, Randy Crawford, Al Jarreau, i Commodores, Julio Iglesias, The Isley Brothers, Dionne Warwick, Ute Lemper, Smokey Robinson, Natalie Cole, Burt Bacharach… un elenco che è ben lungi dall’essere esaustivo. Capace di esaltare proposte sonore vicine all’Adult Oriented Rock come al soul, raffinato ed essenziale in contesti fusion, preciso e implacabile in area rock. |

|

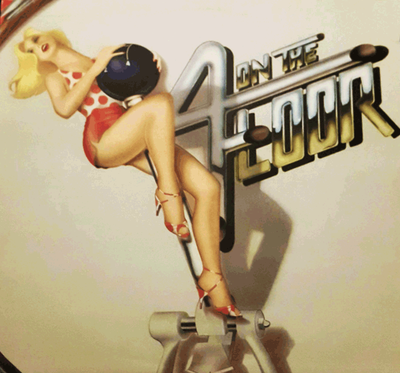

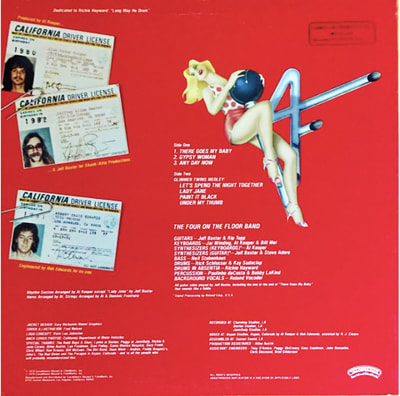

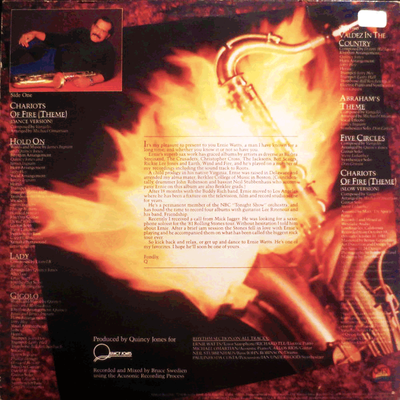

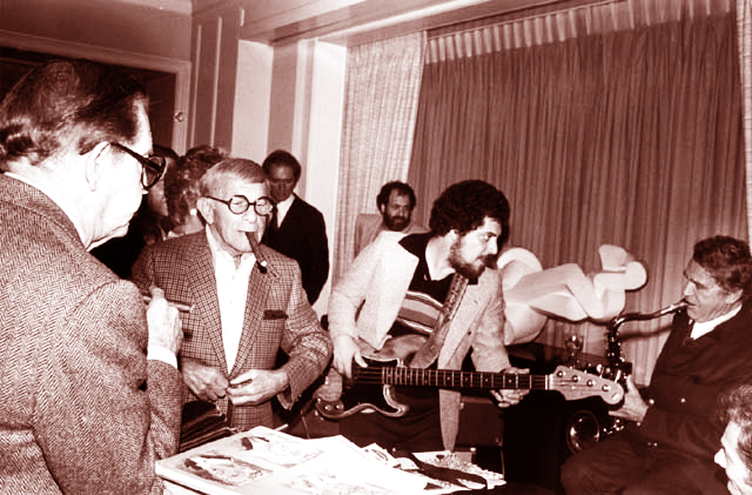

Stubenhaus has left his own mark – well identifiable – on records which went down in history as well as on some composite, creative and elite projects. His throbbing and emotional bass has “sung” everywhere, always going along with the basic laws of groove enhanced with an extraordinary sensitivity. During his breathless and versatile activity as a globetrotter, Neil has played on bass also on some works of italian artists like Eros Ramazzotti and Andrea Bocelli; he has taken part in many sessions in Japan together with the best names of the most sophisticated pop and smooth jazz, and it’s his rich bass the one on the EP called “Four on the floor”, released by Casablanca records in 1979 and produced by Al Kooper, with the ex Deep Purple and Trapez Glenn Hughes as singer. It is not by chance that we mention this album, given that it was the most sought-after item for the experts and entusiasts of bass over the years because of the great Neil’s performance. |

Stubenhaus ha lasciato la sua impronta –ampiamente riconoscibile - in dischi che sono passati alla storia come in progetti compositi e creativi più di nicchia. Il suo basso pulsante e sensibile ha “cantato” ovunque, sempre assecondando la legge basica del groove arricchita da una sensibilità fuori dal comune. Nella sua spasmodica e poliedrica attività di globetrotter, Neil ha suonato il basso anche in lavori di artisti italiani come Eros Ramazzotti e Andrea Bocelli, ha partecipato a numerosissime sessions in Giappone con i migliori nomi del pop sofisticato e dello smooth jazz, ed è suo il pregnante basso nell’ep “Four on the floor”, che uscì per la Casablanca nel 1979, prodotto da Al Kooper e con l’ex Deep Purple e Trapeze Glenn Hughes alla voce. Non a caso citiamo questo album, considerato che per anni è stato oggetto di ricerca da parte dei bassofili per la splendida performance di Neil. |

|

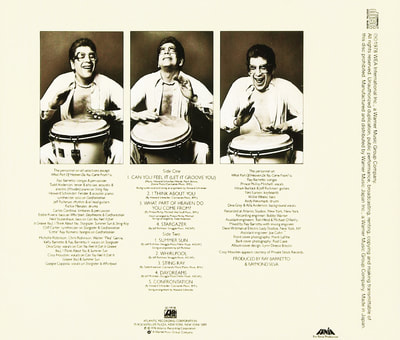

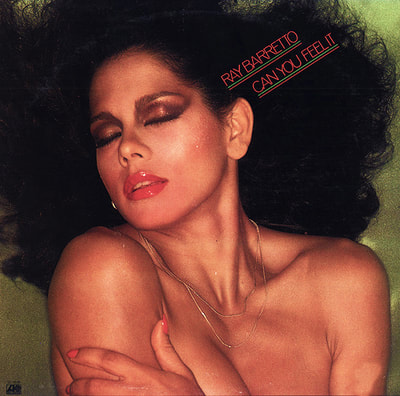

But this is just one of several examples where Neil has been able to make his parts on bass “the leading lines” unintentionally. Which was also the case of Ray Barretto’s records (“Can you feel it”, 1978), Tom Scott, Karizma, Michael Thompson and many others. Well, in short, we are talking about a sort of joker and certainly a real legend of electric bass, a role model for his own skill as bassist who prefers to do his best meticulously, serving the harmonic structure as well as the interplay with the artists (which means the whole world) who needs him and his precious reliability. Neil has given Bass, My Fever this interview which explains the birth and the strengthening of a great star of electric bass, which is brighter than ever even today. |

Ma è solo uno dei tanti esempi in cui Neil ha saputo rendere le parti di basso “protagoniste senza volerlo”, cosa accaduta puntualmente anche in dischi di Ray Barretto (“Can you feel it”, 1978), Tom Scott, Karizma, Michael Thompson e tantissimi altri. Insomma, un jolly e senza dubbio un’autentica leggenda del basso elettrico, esemplare figura di musicista dotatissimo che preferisce scrupolosamente dare il meglio di sé al servizio della struttura armonica e degli artisti (in sostanza il mondo intero) che hanno bisogno di lui e della sua lussuosa affidabilità. Neil ha concesso a “Bass, My Fever” un’intervista che spiega la nascita e il consolidamento di una grande stella del basso elettrico, ancora oggi più brillante che mai. |

|

|

|

A CONVERSATION WITH ONE OF THE MOST SOUGHT-AFTER BASSIST: |

UNA CHIACCHIERATA CON UNO DEI BASSISTI PIù AMBITI: |

|

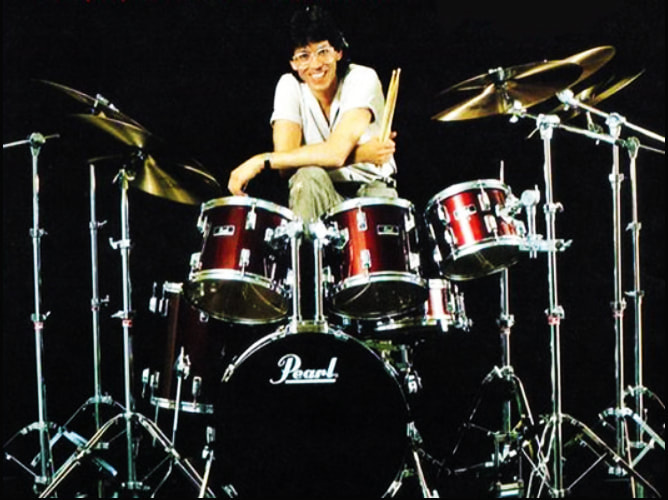

BMF: Let’s start from your beginnings. When and why did you choose electric bass? Neil Stubenhaus: I started taking drum lessons at the age of seven. I was in a band at age ten. My sister brought a junky guitar home one day and showed me what she learned, so I picked it up and got hooked. Within a few months I was playing better than our guitar player, so things changed rapidly and I started a band playing guitar. In time I met a great guitar player who gave me lessons. We eventually became friendly and wanted to start a band together. He said “Why don’t you just play bass?” In the bands I played guitar in, I learned every bass line for every song and taught them to the bass player. I instinctively loved bass, learning all the lines, the feel underneath the music with the power it had to change the direction of the music. So, it was a natural transition. BMF: Which were your first influences about bass and more broadly about music? NS: At first, the most fun was learning Bill Wyman parts (Stones) because they were so unusual and non-intuitive. Remember, that back then, we had old record players and had to lift the needle many times to go back and listen. Tim Bogert and many others had interesting busier lines that I learned more from. Eventually I started listening to more jazz, Ray Brown, Ron Carter, etc. and realized that there was a whole other advanced world out there that combined feel with much more highly progressive music and musicianship. |

BMF: Partiamo dai tuoi inizi. Quando e perché il basso elettrico? Neil Stubenhaus: Ho iniziato a prendere lezioni di batteria all’età di sette anni. Ero in una band a dieci. Mia sorella un giorno mi portò a casa una chitarra messa maluccio e mi mostrò cosa aveva imparato; così me la misi in grembo e ne divenni dipendente. In pochi mesi iniziavo a suonare meglio del nostro chitarrista, perciò le cose cambiarono rapidamente e fondai una band suonando la chitarra. In seguito incontrai un grande chitarrista che mi diede lezioni. Col tempo diventammo amici e mi chiese di fondare una band insieme. Mi disse “Perché non suoni semplicemente il basso?”. Nelle band in cui suonavo la chitarra, avevo imparato tutte le linee di basso di ogni canzone e le insegnavo al bassista. Amavo istintivamente il basso, dal momento che ne memorizzavo ogni nota, il mood nascosto nella musica insieme al potere che aveva di cambiarne la direzione. È stata una conversione naturale. BMF: Quali sono state le tue prime influenze bassistiche e, più in esteso, quelle musicali? NS: All’inizio mi divertiva moltissimo stare dietro alle parti di Bill Wyman (Rolling Stones) perché risultavano inusuali e non intuitive. Ricordo che all’epoca disponevamo di vecchi giradischi e dovevamo ogni volta alzare la puntina per tornare indietro ed ascoltare. Tim Bogert e molti altri avevano linee più impegnative da cui apprendevo di più. Successivamente ho iniziato ad ascoltare di più il jazz, Ray Brown, Ron Carter, etc. e realizzai che c’era tutto un altro mondo all’avanguardia lì fuori che univa la sensibilità con il progressive altamente avanzato e l’abilità musicale. |

|

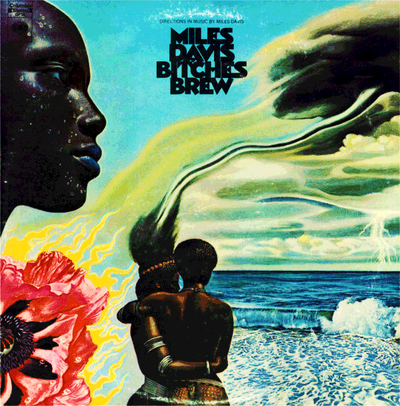

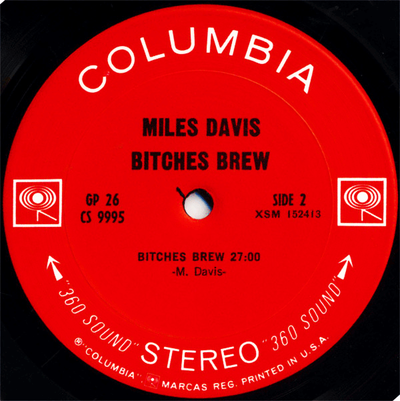

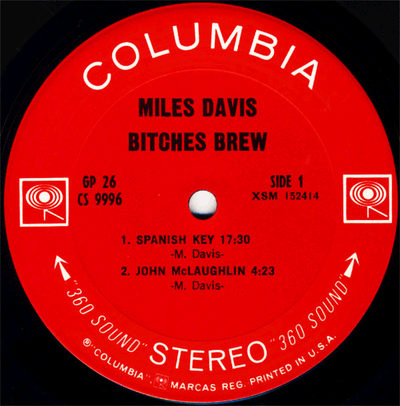

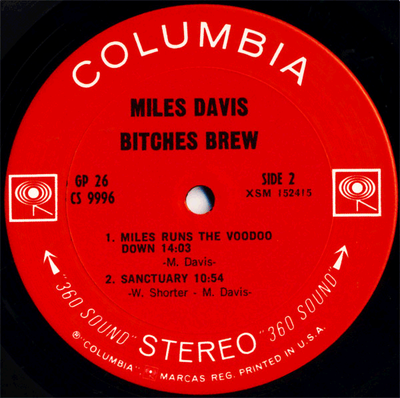

Then discovering "Bitches Brew" changed my music world and led me to another universe. The most fascinating aspect of Bitches Brew (Miles Davis) is that it was the most innovative music for its time, and maybe to this day. It combined the most knowledgeable and accomplished musicians in life (Herbie, Chick, Miles, Wayne, etc.). However, the anchor of that whole project was a bass player named Harvey Brooks. Harvey is a non-jazz but a great R&B feel player, who was not nearly in that same elite league. Miles chose well and way out of the box, a genius casting job. Those Harvey B. bass lines changed my life. He was way out of his usual element theoretically speaking, and yet he was the glue that made the music gel. He brought as equal and pivotal importance to that record as the others did. All with instinct and feel. I can't emphasize how important Harvey’s playing, his groove, and hence, his role was. That’s what makes a bass player great rather than just really damn good. To date, I’ve never had the pleasure of speaking to Harvey. Wish me luck.

|

La scoperta di Bitches Brew (Miles Davis) diede una svolta alla mia visione della musica conducendomi in un altro universo. L’aspetto più affascinante dell’album era il suo spirito innovativo per il tempo, il che forse vale anche per i giorni nostri. Riuscì a mettere insieme i musicisti più competenti ed esperti in assoluto (Herbie, Chick, Miles, Wayne, etc.). Ad ogni modo l’àncora dell’intero progetto fu un bassista di nome Harvey Brooks, non un musicista jazz bensì di matrice R&B, che era ben lungi dall’appartenere a quello stesso pedigree di fuori classe. Miles scelse bene e decisamente fuori dagli schemi, una selezione del casting davvero geniale. Quelle linee di basso di Harvey B. cambiarono la mia vita. In teoria si trovava decisamente fuori dalla sua dimensione abituale, ciononostante lui era il collante in grado rendere densa la musica. Seppe dare un’impronta altrettanto cruciale al disco rispetto agli altri. Il tutto con istinto e sensibilità. Non so sottolineare abbastanza quanto sia stato importante il modo di suonare di Harvey, il suo groove, ergo, il suo ruolo. Ecco cosa rende grande un bassista e non solo dannatamente bravo. Finora non ho mai avuto il piacere di parlare ad Harvey. Auguratemi buona foruna. |

|

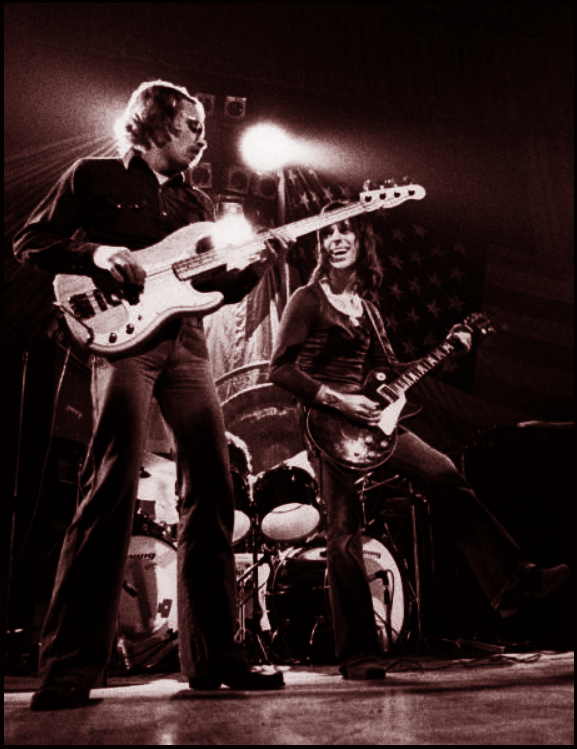

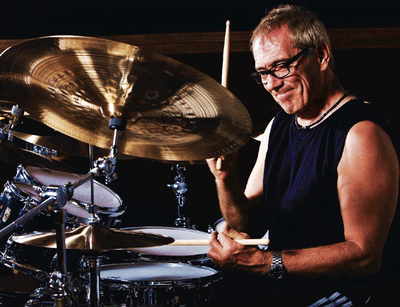

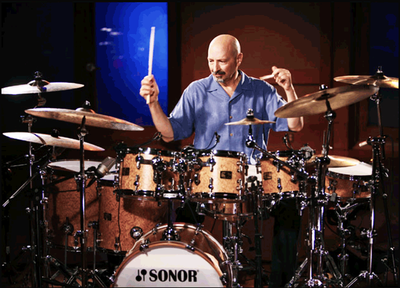

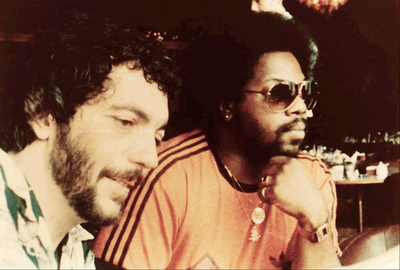

BMF: You’re a legend of electric bass, which is undisputable and not just for your great skill but also because you have proved through your long path, that you can be creative and influential in every scene also as a powerful session man… You have played everything with the best names of any music movements. How did you manage so different engagements and projects? NS: That’s very kind of you to say. There is no answer to that, other than the way we as human beings manage life as it comes to us with what we have. When there is a challenge, we rise to the occasion. When your life is in danger, you do what you never knew you were capable of. Musically, magic happens when reach within, and find what we did not know was there. Much of it happens in a fast moment. BMF: Would you like to talk about any of your music encounters which were the most significant for you? NS: There are so many, and I had many fortuitous encounters that all make me feel like a very lucky person. Meeting Quincy Jones is a stand out, he was one of my idols. I was in the right place in the right time period of life. Jay Graydon says we hit the musical lottery. I agree. I went to Berklee in the 70’s and was in school with Vinnie Colaiuta, Steve Smith, John Robinson, Mike Stern and others. Mike recommended me for Blood Sweat & Tears in 1977. That was a gift, a fabulous musical fun experience and a great learning curve for me. To this day, JR and Vinnie are the drummers I have played with mostly on numerous sessions. Who could have predicted that? I’d love to list all the many encounters, but that would be more like a book. |

BMF: Sei una leggenda del basso elettrico, è fuori discussione. Non solo per le grandi capacità tecniche, ma anche perché hai dimostrato, con la tua storia, che si può essere creativi e influenti su ogni scena anche come session-man di lusso… hai suonato praticamente di tutto con i migliori nomi di ogni corrente musicale. Come si vive da musicista indaffaratissimo e richiestissimo? Come hai gestito la pianificazione di tanti impegni? NS: Sei molto gentile a dire questo. Non ho una risposta per questo, se non fare riferimento al modo in cui gestiamo le nostre vite come esseri umani, si tratta di noi e di quello che abbiamo. Quando si prospetta una sfida noi dobbiamo cogliere l’occasione. Quando la tua vita è in pericolo, tu reagisci nel modo in cui non avresti mai pensato di essere capace. Dal punto di vista musicale la magia ha inizio quando sembra a portata di mano, e trovi quello che non pensavi fosse lì. Molto di questo accade in un attimo. BMF: Quali sono stati gli incontri musicali che ti hanno arricchito di più in assoluto? NS: Ce ne sono così tanti, ho avuto molti incontri fortuiti che mi hanno fatto sentire una persona fortunata. Incontrare Quincy Jones è qualcosa che segna, è stato uno dei miei idoli. Mi trovavo al posto giusto nel momento giusto della mia vita. Jay Graydon dice che abbiamo vinto alla lotteria. Sono d’accordo. Andai a Berklee negli anni settanta e andavo a scuola con Vinnie Colaiuta, Steve Smith, John Robinson, Mike Stern ed altri. Mike mi raccomandò ai Blood Sweat & Tears nel 1977. Il che è stato un dono, un’esperienza musicale divertente ed una curva di apprendimento grandiosa per me. Sino ad oggi, JR e Vinnie sono i batteristi con cui ho suonato di più in numerose session. Chi l’avrebbe detto? Mi piacerebbe elencare tutti i miei incontri, ma ci vorrebbe qualcosa di più di un libro. |

|

BMF: I’ve always wondered why you didn’t yet make an album under your name. I think it could be fantastic so I’m curious to ask you this: to what kind of music would a possible record of your own be oriented? To jazz, Westcoast, pop…?

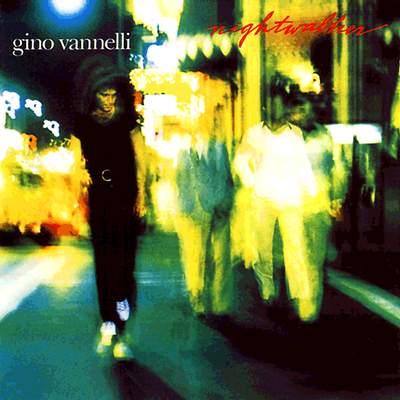

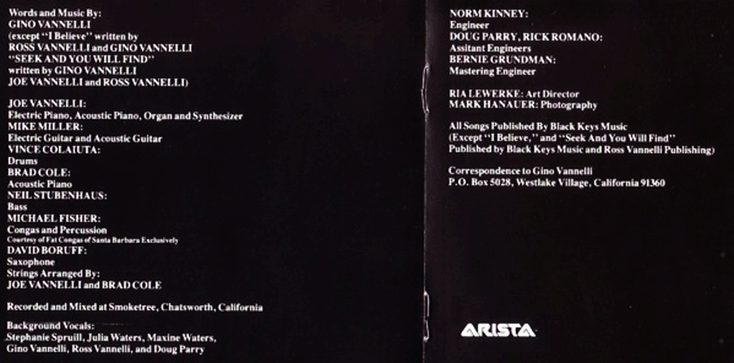

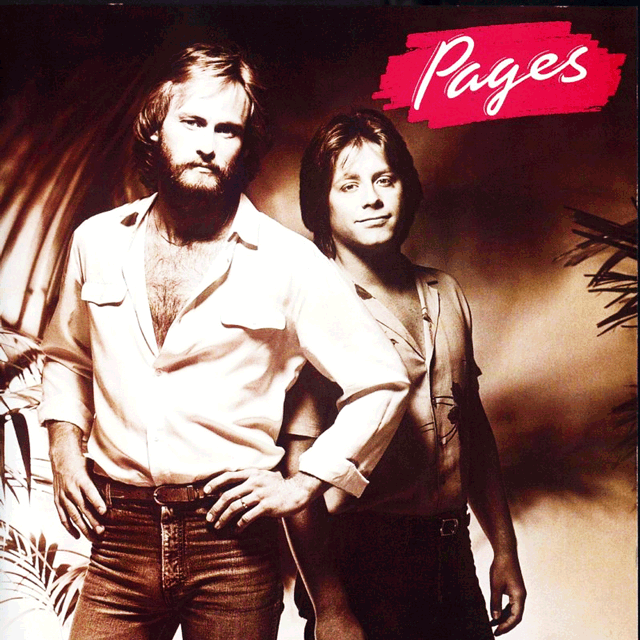

NS: I've had ideas in mind for many years. Primarily, it would be a serious investment in time, and most of my life has been a mixture of hard work and fun free time. Candidly, I never thought of myself as an absolute self starter, I always let the world lead me, which for the most part it did just that. In my own insecurity, I never thought I could live up to my own standards. I’m not a show off bass player, I mostly rely on interplay. There are too many great players that make records which show off their playing on a bed of ordinary material. A great album project for me is all about great material. Great playing reacts to great material. That’s something that takes focus and dedication, and maybe someday I’ll make that commitment. BMF: Among your infinite collaborations, I’d like to focus on just some of them like for instance those ones with Gino Vannelli and the beautiful album “Nightwalker”; your long collaboration with Tom Scott, not to mention George Benson, Quincy Jones, Solomon Burke.. Could you tell us any stories or memory about those experiences? NS: Taking these one at a time: Gino was a fascinating experience. It was the only record project in my career that was booked for 8 weeks. I recommended Vinnie. We carpooled everyday to Gino’s project, then every night to the Pages project. Good thing I was young! Through ups and downs and major changes in songs, parts, and song choice, we got it done. Gino realigned a ton of it and tweaked it to perfection after the recordings, then I overdubbed all my parts after the fact. All over again! The more time you have, the more you change your mind. Gino is a highly superior artist, musician and performer who never got his due in my opinion. He got fucked… thank you Clive Davis. Typical music business politics. |

BMF: Mi sono sempre chiesto come mai tu non abbia inciso ancora qualcosa a tuo nome. Credo che sarebbe fantastico e mi incuriosisce chiederti: un tuo disco solista sarebbe orientato al jazz, alla Westcoast, al pop…? NS: Mi sono venute in mente alcune idee per diversi anni. In primo luogo, sarebbe un serio investimento di tempo, e gran parte della mia vita è stata un misto di lavoro duro e tempo libero finalizzato al divertimento. Francamente, non ho mai pensato a me stesso come ad una persona dotata di un vero spirito di iniziativa, ho sempre lasciato che il mondo mi guidasse, il che è accaduto per la maggior parte delle volte. Per la mia insicurezza non ho mai pensato di essere all’altezza dei miei standard. Non sono un bassista che si mette in mostra, punto più che altro all’interplay. Ci sono fin troppi bravi musicisti che fanno dischi per esibire il loro stile su di un letto di materiale comune. Un bel progetto per me è tutta una questione di lavoro di valore. Un ottimo sound reagisce a dell’ottimo materiale. È qualcosa su cui bisogna concentrarsi e dedicarsi e forse un giorno mi assumerò quell’impegno. BMF: Tra i tuoi innumerevoli incontri, vorrei soffermarmi con te su alcuni in particolare. Quello con Gino Vannelli, con cui hai suonato nel bellissimo “Nightwalker”. La tua lunga collaborazione con Tom Scott… e ancora, George Benson, Quincy Jones, Solomon Burke… ci puoi raccontare qualche aneddoto e i tuoi ricordi? NS: Li prenderò in considerazione uno alla volta: Quella con Gino è stata una esperienza affascinante. È stato il solo disco nella mia carriera ad esser prenotato per otto settimane. Io raccomandai Vinnie. Arrivavamo insieme ogni giorno al progetto di Gino e poi ogni notte a quello di Pages. Fu utile che io fossi giovane! Tra alti e bassi e grandi cambiamenti alle canzoni, alle parti e la scelta dei pezzi, ce l’abbiamo fatta. Gino riallineò molto del lavoro, ottimizzandolo alla perfezione dopo la registrazione, poi io incisi tutte le mie parti a posteriori. Tutto da capo! Quanto più tempo hai a disposizione, tanto più cambi idea. Gino è un artista di gran lunga superiore, un musicista ed un performer che non ha mai ottenuto il riconoscimento dovuto a mio avviso. È stato fregato… Grazie Clive Davis. Le tipiche strategie piegate al business musicale. |

|

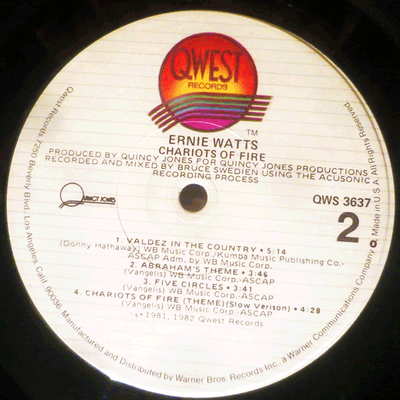

Tom Scott called me out of the blue to record on a Saturday with Richard Tee, Steve Gadd, Eric Gale and Hugh McCracken. I was in San Francisco on a gig with Seals & Crofts and couldn't leave. I was stunned. Tom had heard me at a TV session and I wasn’t aware that he liked what he heard. With Tom I was introduced to the primo New York talent, and a lot of LA talent including Jeff Porcaro. I did 10 great records with Tom, many movies, TV shows, and other memorable gigs. I am forever indebted to Tom and we remain good friends. I have done a few recordings with George Benson, as well as a few live gigs, and it’s always an honor. He knows my playing and when he can't see me he yells, “Is that you, Neil?” What a thrill. He likes me, and I’m honored. My friendship with Quincy started in 1982 on an Ernie Watts record that Quincy produced. What a blast that was. I’ve been working with him ever since. He’s the ultimate musician, producer and all around human being on the right side of the human equation. There are occasions when I get lucky enough to talk with him alone for hours. What an honor! I worked with Solomon Burke via Gene Page, who back in the day arranged and produced myriad songs for myriad artists from Whitney Houston to Solomon Burke. We were all surrounded by major talent. |

Tom Scott mi chiamò all’improvviso per registrare un sabato con Richard Tee, Steve Gadd, Eric Gale e Hugh McCracken. Mi trovavo a San Francisco per un concerto con i Seals & Crofts perciò non potevo partire. Rimasi senza parole. Tom mi aveva sentito durante una session in Tv e non ero convinto che gli fosse piaciuto quello che ascoltò. Con Tom fui presentato ai migliori talenti di New York, e ad un mucchio di grandi artisti di Los Angeles tra i quali Jeff Porcaro. Ho fatto dieci grandi album con Tom, molti filmati, show televisivi, ed altri concerti memorabili. Gli sarò debitore a vita e siamo rimasti ottimi amici. Ho inciso pochi dischi con George Benson, inclusi alcuni concerti live, ed è sempre un onore. Lui riconosce il mio stile e quando non può vedermi esclama sempre: “Sei tu, Neil?” Che emozione. Gli piaccio e ne sono onorato. La mia amicizia con Quincy è iniziata nel 1982 con un disco di Ernie Watts prodotto da lui. Fu uno spasso. Non avevo mai lavorato con lui prima di allora. È il musicista e produttore più grande, l’essere umano che si coll0ca dalla parte giusta dell’equazione. Ci sono occasioni in cui sono fortunato di parlare da solo con lui per ore. Che onore! Ho collaborato con Solomon Burke attraverso Gene Page, il quale all’epoca arrangiò e produsse miriadi di canzoni per miriadi di artisti, da Whitney Houston fino a Solomon Burke. Eravamo tutti circondati dai migliori talenti. |

|

BMF: One of the most impressive aspects of your style is that your sound is recognizable both on fretted and fretless. I can listen to a record by Barbra Streisand or Julio Iglesias, and right away I say to myself: «Now, this is Neil Stubenhaus…». It’s not so common this! How would you explain that to our readers?

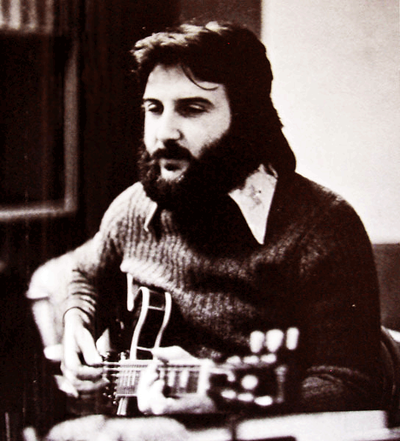

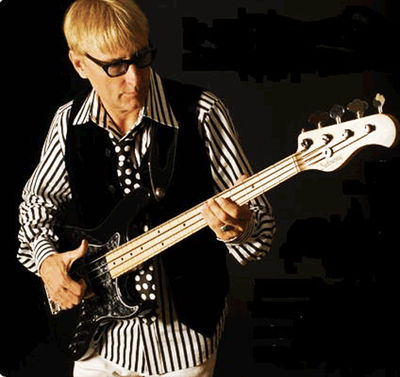

NS: I don’t think this is complicated, I could just say that I hear it the way I hear it and play it that way. There’s no calculation, it’s natural. I immerse myself into the song and play without deliberately thinking. The playing is a natural extension of my personality, as I think it is with everyone. I doubt I can do what I do any differently if I tried. Here’s an indulgent anecdote regarding an artist experience and bass importance so as to give you the gist of it: I was doing a song with Ray Charles for a Warren Beatty movie. Marty Paitch (RIP) arranging and conducting, 40 or so musicians. Ray wasn’t there yet, so Marty did several takes with variations; one had stronger strings, one had stronger woodwinds, all slight variations of the arrangement that Marty assumed Ray would choose from. Ray showed up, we were in the booth and listened. Marty took over and told Ray: this one has bla bla strings and this one has bla bla horns, and Ray stopped him after only hearing 2 versions and said, “I’m just listening to the bass and this one knocks me out. Let’s move on to the vocals.” The room got really quiet. and I stared for a moment at the contractor. I never got the extra $40. BMF: Over so many years of career, I’d like you to mention me the basses of which you have been endorser, and which were your favorites ones. And what about your current gear? NS: I have owned many basses over the years, but I remain a Fender style guy. There are so many to choose from. I looked into jazz basses many years ago which was validated by Jaco in 1973. I say “style” because many brilliant perfectionist bass luthiers have improved on the basic Fenders, including Fender these days. Back in the early 1980’s, I met James Tyler who was a small time guitar repairman with a small shop. He was always there for me. After my main Fender was stolen, which he modified in many ways, he started making basses for me from scratch. I have every one of them to this day, one (5-string) which was stolen twice and I got it back twice. That bass is my main bass. I’m forever indebted to James Tyler, he was always right there for me. Frankly, I’ve lost interest in the quest for newer, different, better, and all that. My interests have gone in many other directions. |

BMF: Una dei tanti aspetti che colpisce di più nel tuo stile è che il tuo suono, tanto al fretted che al fretless, è riconoscibile. Posso ascoltare un disco di Barbra Streisand o di Julio Iglesias, e subito mi dico “ecco, questo è Neil Stubenhaus…”. Non è così comune questo! Come lo spiegheresti ai nostri lettori? NS: Non credo che sia così complicato. Posso solo dire che io ascolto come ascolto e suono allo stesso modo. Non c’è nessun calcolo dietro, è una cosa istintiva. Mi immergi nella canzone e suono senza pensare volutamente. Il mio stile è una estensione naturale della mia personalità, come credo che sia per ciascuno. Dubito di poter fare quello che faccio in maniera diversa anche se ci provassi. Eccovi un aneddoto indulgente relativo ad un’esperienza artistica e all’importanza del basso che dovrebbe rendere un po’ l’idea: lavoravo ad una canzone con Ray Charles per un film di Warren Beatty. Il committente fece confusione pagandomi 40 dollari in meno di quelli che avevo chiesto. Marty Paich (RIP) arrangiava e dirigeva un gruppo di quaranta e più musicisti. Ray non era ancora arrivato, perciò Marty fece diverse tracce con alcune variazioni; una aveva corde più potenti, un’altra aveva dei fiati più in evidenza, tutte variazioni leggere dell’arrangiamento che Marty presupponeva venissero vagliate da Ray. Probabilmente sei versioni in tutto. Ray si presenta e va dritto nella cabina ad ascoltare. Marty si fece avanti vantandosi con Ray: questa ha bla bla numero di corde, e quest’altra questi bla bla di fiati, al che Ray lo fermò appena dopo la seconda traccia, dicendo: “Mi interessa solo il basso e questo mi ha colpito. Usiamolo. Passiamo alle parti vocali.” La stanza piombò nel silenzio più assoluto e fissai per un momento il committente. Non ottenni mai quegli altri 40 dollari che mi spettavano. BMF: In tantissimi anni di carriera, voglio chiederti di quali bassi sei stato endorser e testimonial. E, in assoluto, quali hai preferito. La tua strumentazione attuale, ce ne parli? NS: Ho posseduto molti bassi nel corso degli anni, Ma rimango fedele al Fender style. Ce ne sono così tanti tra cui scegliere. Tra i bassi jazz molti anni fa ne cercai uno che fu validato da Jaco nel 1973. Dico “Style” perché molti liutai perfezionisti del basso lo hanno migliorato a partire dai principali Fender, inclusi i Fender di oggi. Nei primi anni ’80, incontrai James Tyler che era un modesto riparatore di chitarre con un piccolo negozio. Era sempre lì per me. Dopo che mi rubarono il mio basso Fender principale, che lui mi modificò in molti anni, iniziò a creare dei bassi per me da zero. Li posseggo tutti ancora oggi, un cinque corde che mi è stato rubato due volte, ed altrettante l’ho recuperato. Quel basso è il mio principale. Sarò sempre debitore nei confronti di James Tyler, era sempre disponibile, lì apposta per me. Onestamente, ho perso l’interesse nella ricerca del più nuovo, differente, migliore e tutte le cose messe insieme. I miei interessi hanno preso direzioni completamente diverse. |

|

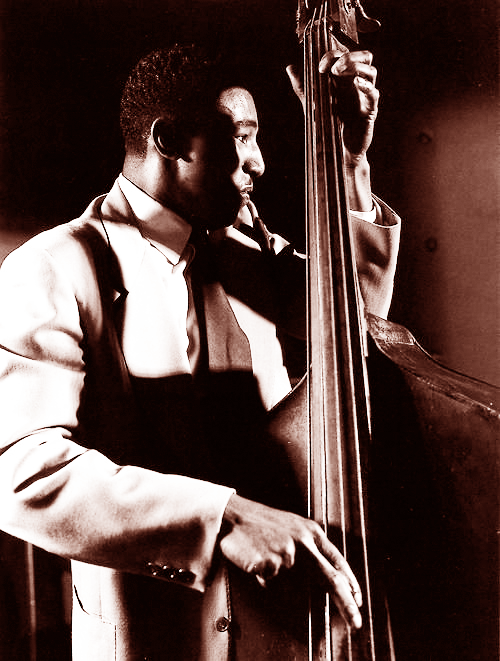

BMF: Just out of curiosity, what’s your relationship with double bass? NS: I own one, I studied at Berklee and gave it a shot. I don’t think I ever really had the discipline and dedication to set the amount of time aside to get really proficient at it, let alone the raw talent to be as good as so many of my peers. I was deterred being in Boston in the cold even thinking about carrying it around! I wouldn't do it marginally just so I could say that it’s in my arsenal. There are so many deserving upright players that are fabulous, so I feel that work should go to one of them. I struggled with this early on, but found peace with leaving it be. BMF: I’d like to know who are the bassists who make you feel closer to and whom you hold in great esteem. You belong to a dream team of bass players constantly glorified by the enthusiasts and the insiders, along with Will Lee, Abraham Laboriel, Anthony Jackson… NS: I greatly admire everyone you mentioned, but Anthony I regard as a unique genius of electric bass. Everything he plays on is a bass masterpiece, while simultaneously serving the best interest of the music. That said, there are so many great bass players, I consider myself more of a medium sized fish in a rather large pond. |

BMF: Una curiosità. Il tuo rapporto con il contrabbasso? NS: Ne posseggo uno, ho studiato a Berklee e ci ho provato. Non credo di esser mai stato dotato della disciplina e dedizione necessarie per stabilire la quantità di tempo utile a diventare davvero bravo, per non parlare del talento naturale per essere altrettanto capace rispetto ai miei colleghi. Ero scoraggiato dal rimanere a Boston al freddo al solo pensiero di portarmelo in giro! Non lo farei solo in misura marginale perciò potrei dire che è nel mio arsenale. Ci sono così tanti contrabbassiti meritevoli che sono favolosi, dunque sento che quel lavoro debba essere di uno di loro. Ho combattuto con questo fin dagli inizi poi ho trovato la mia pace accettando che fosse così. BMF: Vorrei sapere da te quali sono i colleghi che stimi di più e quali bassisti, oggi, reputi migliori. Tu fai parte di quel dream team di bassisti che tutti gli appassionati e gli addetti ai lavori celebrano costantemente, con Will Lee, Abraham Laboriel, Anthony Jackson, Marcus Miller… NS: Ammiro enormemente ogni artista che hai citato, ma Anthony lo ritengo il genio unico del basso elettrico. Qualsiasi cosa suoni è un’opera d’arte bassistica, mentre al contempo è intento ad agire nell’interesse della musica. Detto questo ci sono così tanti bassisti grandiosi, tanto che considero me stesso un pesce di media taglia in uno stagno piuttosto grande. |

|

BMF: Over so many years of collaborations (also in studio) have you ever met Chuck Domanico? Did you know him personally?

NS: I knew Chuck very well, we were on many film sessions and a good few record sessions together. It’s interesting that you should mention him, Chuck is one of the most underrated upright players ever. He played on zillions of films, tv shows and records. Everyone in the world has heard him unless you lived in a cave. Brilliant musician, a real BASS player, not a single extraneous note, no fluff, and when he played and you felt the downbeat of life. Never a mistake. Big fat sound. Taste, touch, tone. If a composer wrote something that didn’t make sense, he got busted by Chuck. We had a mutual respect that was pure admiration. We lost him 15 years ago and I miss him still, as does the music world. PS, please don’t smoke cigarettes. BMF: You are surely the right person with whom we could reflect on the evolution of electric bass. Many bassists have never “come out of Jaco Pastorius’s shadow”, and they’ve been trying to emulate him vainly, so they shall refrain from finding their personal “voice”, which is the thing that you’ve been able to do it in the best way possible. Do you think that it could be possible a further development of bass expressivity? Is it an instrument with a margin for evolution? NS: We now have many bass applications. First, the bass player who supports a body of music; the bass is supportive, has room to be heard and much appreciated, but is not the star of the show. (except sometimes to many of us!) Second, we have bass stars, many of them these days. They make solo records, they are up front and extraordinary, as well as supportive. John Patitucci! He does it all. True monster of all matters bass. Lastly there are bass lovers, they play, they mimic, they sound like others, especially Jaco, and they are in search mode, some closer to a voice of their own than others. This is not meant to be a slight at all. As long as they love what they’re doing, all the power to them. Everyone should enjoy playing without worry that they need to be SOMEONE or it’s all for naught. One should feel free to love playing bass just for bass, it’s all good. There are also very few like Marcus Miller, a true genius bass player multi talent, with noticeable Jaco influence like the rest of us. Marcus tips his hat deliberately, with individual style, once in a while when called for. Let’s face it, Jaco changed the world of bass. He changed it for me in a big way. I should also credit him for helping to make me confident enough to leave my upright in the closet. He was a friend and I cherished that lucky friendship. A Jaco, a Hendrix, a Brecker comes along once in a lifetime. I can't predict if there is more evolution to come, but anything can happen. Expression is individual, and in the ear of the beholder. |

BMF: Nelle tue tante frequentazioni musicali e di studio, hai mai incrociato Chuck Domanico? Lo conoscevi personalmente? NS: Conoscevo molto bene Chuck, eravamo insieme im molte session per i film ed un buon numero di registrazioni. È interessante che tu me lo abbia citato, Chuck è uno dei contrabbassisti più sottostimati in assoluto. Ha suonato in un infinità di film, show televisivi e dischi. Chiunque al mondo ha avuto occasione di ascoltarlo a meno che non abbia vissuto in una caverna. Un musicista brillante, un vero bassista, non una sola nota superflua, niente fesserie, quando suonava potevi sentire il ritmo della vita. Mai uno sbaglio. Un sound gigantesco. Gusto, tocco, colore. Se un compositore avesse scritto qualcosa privo di un senso, veniva beccato da Chuck. Nutrivamo un rispetto reciproco che si traduceva in pura ammirazione. Lo abbiamo perso quindici anni fa e ancora mi manca, e altrettanto al mondo musicale. PS, mi raccomando non fumate sigarette. BMF: Sei la persona più adatta con la quale fare una riflessione sull’evoluzione del basso elettrico. Molti bassisti non sono mai usciti dal cono d’ombra di Jaco Pastorius, cercando vanamente di emularlo e non trovando una “voce” personale, cosa che tu invece sei riuscito a fare benissimo. Credi ci sia ancora la possibilità di innovare il linguaggio del basso? È uno strumento con ancora margini di evoluzione? NS: Noi adesso abbiamo numerose collocazioni diverse. Per prima cosa il bassista che supporta un complesso; il basso è di supporto, ha un margine per essere ascoltato ed è molto apprezzato, ma non è la star dello spettacolo (fatta eccezione alcune volte per molti di noi!) Secondo poi, abbiamo le star del basso, molte di loro lo sono attualmente. Incidono dischi solisti, sono in prima fila e straordinari, oltre che di sostegno. John Patitucci! Riesce in tutto. Un vero e proprio mostro per chiunque si occupi di basso. In ultimo ci sono gli appassionati di basso, che suonano, imitano, risultano come altri, specie sulla falsa riga di Jaco, e sono nella modalità di ricerca; alcuni più prossimi a trovare la propria voce rispetto ad altri. Questo non è affatto da prendere alla leggera. Fin quando amano quello che fanno, buon per loro. Tutti dovrebbero divertirsi suonando senza preoccuparsi di aver bisogno di essere qualcuno o non servirà a niente. Uno dovrebbe sentirsi libero di suonare con amore il basso solo per il basso, va bene così. Ci sono davvero pochi artisti come Marcus Miller, un vero genio dello strumento con un talento molteplice, con una evidente ispirazione a Jaco come tutti noi del resto. Marcus Miller solleva il cappello intenzionalmente, con uno stile individuale, di tanto in tanto quando è chiamato a farlo. Diciamoci la verità, Jaco ha rivoluzionato l’universo del basso. Lo ha cambiato in un modo grandioso per me. Dovrei inoltre ringraziarlo per avermi aiutato a prenderci confidenza a tal punto da lasciare il mio contrabbasso nell’armadio. Era un amico ed ho apprezzato quella fortunata amicizia. Un Jaco, un Hendrix, un Brecker capitano una volta nella vita. Non posso predire se ci sia ancora un margine di evoluzione, ma tutto può succedere. L’espressione è individuale, e nell’orecchio di chi assiste. |