INTERVIEW WITH

STEVE YORK

|

«To me ensemble music at it’s best is a conversation between musicians and to participate the bassist needs to learn the language, vocabulary and grammar of whatever style of music is being played and then to have some ideas to bring to the conversation and also to be capable of supporting and playing around the ideas of others»

.............. «Per me la musica d’insieme è - nella migliore delle ipotesi - una conversazione tra musicisti e per partecipare il bassista ha bisogno di apprendere il linguaggio, il vocabolario e la grammatica di qualsiasi stile di musica lui si trovi a suonare ed in un secondo tempo di elaborare alcune idee con cui arricchire lo scambio di battute ed essere in grado di supportare e ricamare sulle idee degli altri» |

|

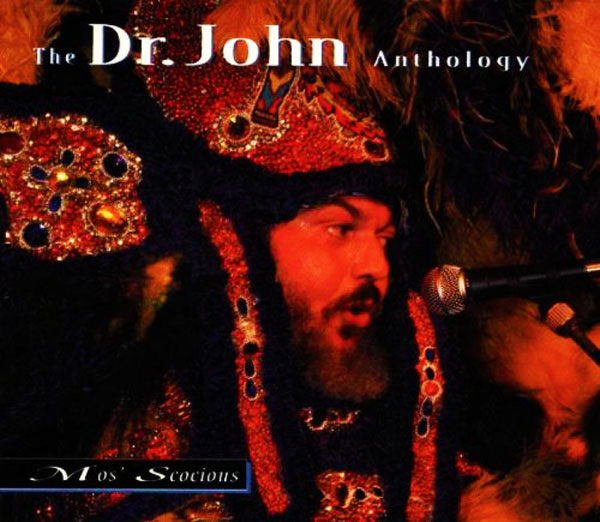

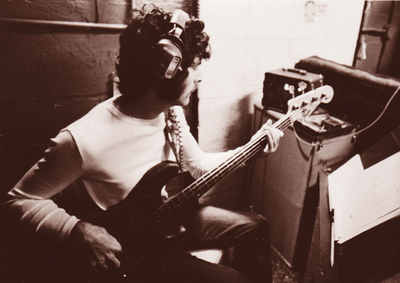

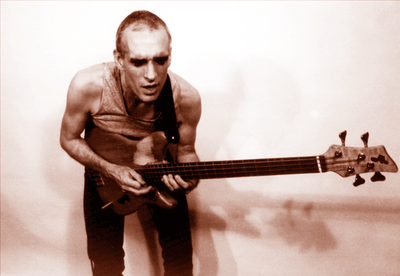

Steve York is a bassist with a really solid background. He’s the perfect partner for several musical contexts ans he’s definitely a musician who in a long and honourable career has combined reliability with creativity, which is one of the rarest skill. Steve has made available his bass playing to the very cream of UK and US rock; the pioneering adventure together with Manfred Mann, his art-prog history with the unforgettable East Of Eden, three seminal albums along with Vinegar Joe the band which he shared with Robert Palmer and Elkie Brooks. And moreover his gold collaborations with Marianne Faithfull, Dr John as well as the great and always regretted Graham Bond who is a key figure in the uk rock-blues scene between the late Sixties and the mid-1970's. |

Steve York è un bassista dal background solidissimo, un partner ideale per molteplici contesti e, in assoluto, un musicista che in una lunga e onorata carriera ha sposato l’affidabilità alla creatività. Aspetto molto più raro di quel che si possa pensare. Steve ha prestato i suoi servigi alla crema del rock britannico e statunitense; la pionieristica avventura con Manfred Mann, i trascorsi art-prog con gli indimenticati East Of Eden, tre seminali cd con i Vinegar Joe, la band condivisa da Robert Palmer ed Elkie Brooks. E ancora, le auree collaborazioni con Marianne Faithfull, Dr. John e il grande e sempre rimpianto Graham Bond, figura cardine della scena rock blues britannica a cavallo tra fine ’60 e metà anni ’70. |

|

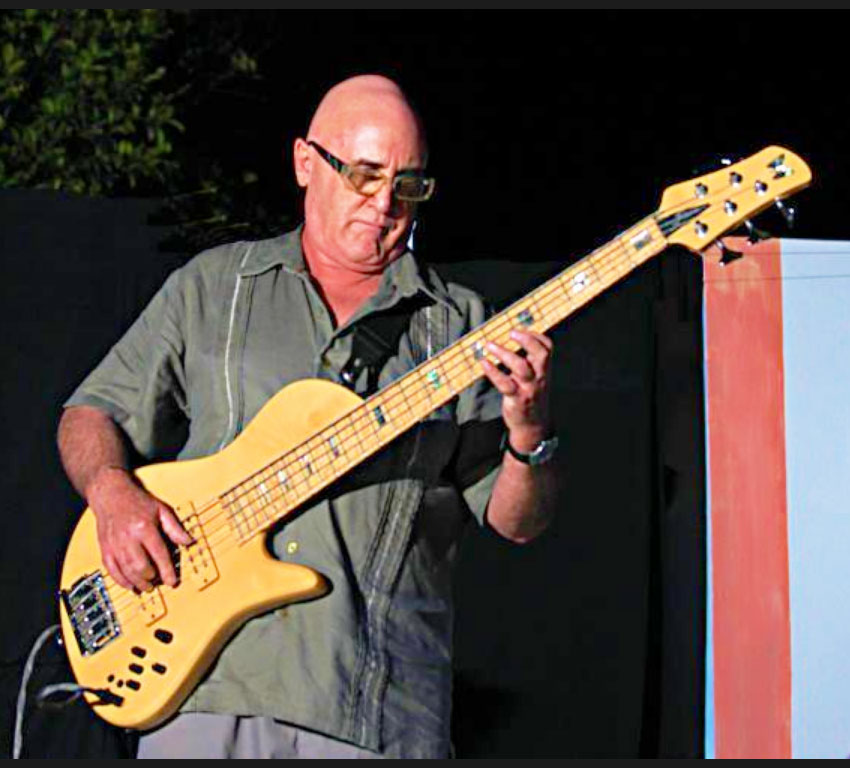

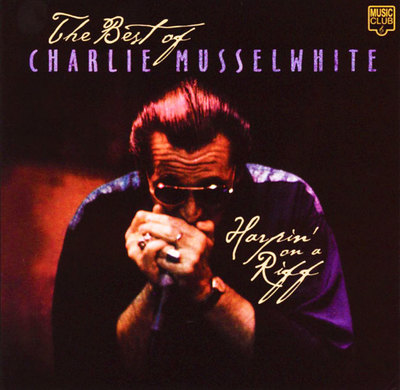

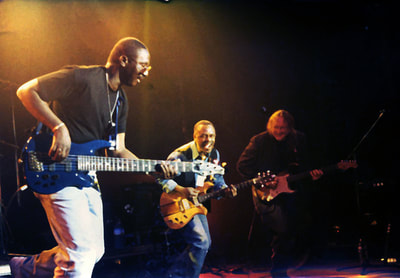

But the list is far from being completed: it’s impossible not to mention his path with Arthur Brown, the elegant Joan Armatrading and such extraordinary blues harmonica player Charlie Musselwhite. In addition to be an endorser of the biggest electric bass brands, among other things, Steve York is also a creative architect of the instrument as well as a musician able to listen to his collegues, to develop the contexts in which he’s involved and therefore to do the best. His basslines are never ordinary nor merely limited to an intangible support; on the contrary they’re characterized by a cultured vividness which is never an end in itself but this is a sound shaped by the propulsive and driving gait of the rythm section. |

Ma l’elenco è ben lungi dall’essere esaustivo: impossibile non menzionare i suoi trascorsi con Arthur Brown, l’elegante Joan Armatrading e l’esplosivo armonicista blues Charlie Musselwhite. Steve York, tra l’altro iconico endorser di marchi bassistici superiori quali Lakland e Fodera, è un delizioso architetto del basso elettrico ed un musicista atto ad ascoltare gli altri, interpretare il contesto e dunque dare il meglio. Le sue linee di basso non sono mai banali e mai meramente limitate a un supporto impalpabile; anzi, si contraddistinguono per una vivacità colta e mai sterile, improntate ad un andamento prosodico e scattante della funzione ritmica. |

|

Steve York is a musician whom most of nowadays bassists should listen to carefully and humbly so as to better understand (or discover for the first time) that the interplay gained through playing with other musicians is the most authentic school of musical intelligence, they should learn that listening to the others is fundamental and that it makes no sense to play on prerecorded tracks or to embark on tedious competitions with themselves. Steve – who has been residing in Mexico for several years and there keeps playing and instilling his seductive teaching - has granted us this really complete and inspiring interview both for the insiders and the enthusiasts of music. His profile and background are so unique and far-reaching as the ones of the greatest artists. |

Un bassista che molti dei bassisti di oggi dovrebbero ascoltare con attenzione ed umiltà, per comprendere forse meglio –o sentir parlare di questo per la prima volta, chissà- che suonare insieme è la palestra più autentica dell’intelligenza musicale, che l’ascolto degli altri è fondamentale e che non ha senso misurarsi con basi pre-registrate o intraprendere noiose gare di velocità con se stessi. Steve, che risiede in Messico da diversi anni e lì continua a suonare e infondere felicemente la sua seducente didattica, ci ha rilasciato un’intervista molto completa e davvero stimolante, per gli addetti ai lavori come per gli appassionati di musica. Un profilo, il suo, unico e di grande respiro. |

|

UNA VITA SPESA PER LA MUSICA, ALL'INSEGNA DELL'AMORE PER LE BASSE FREQUENZE |

|

BMF: Steve, would you like to talk about your beginnings and why you chose electric bass? STEVE YORK: My grandfather and grandmother were professional pianists. My grandfather was a concert pianist and did very well in the 1920’s. My grandmother played for silent movies. My mother was a concert quality pianist but did not like to perform in public. My grandfather used to write his own extemporizations to Bach’s compositions. My job from the age of three was to turn the pages of the sheet music when they practiced, usually eight bars ahead. My grandparents and my mother liked jazz, especially Art Tatum, Duke Ellington and Count Basie, and, later, Miles Davis. I heard Count Basie with Joe Williams at a London concert when I was 11 years old. Although I was fascinated by drummer Sonny Payne, I came away with the bass lines stuck in my head and knew that I wanted to play bass. I had some lessons on upright bass, and took up electric bass at the age of 14 in 1962, when it was a relatively new instrument. About fifteen years ago I was fitted for custom earplugs which had a flat frequency response for musicians and received a note from the manufacture that they could not guarantee a flat response, in my case, because I have unusually long ear canals that accentuate the bass response. I think that may be a reason why I was attracted to bass as an instrument. Apparently I hear more of it than most people! |

BMF: Steve, ci puoi raccontare dei tuoi inizi e perché hai scelto il basso elettrico? STEVE YORK: Mio nonno e mia nonna erano dei pianisti professionisti. Il primo era un concertista e realizzò molte cose negli anni ‘20. Mia nonna suonava per i film muti. Mia madre era una pianista di un certo livello ma non amava esibirsi in pubblico. Mio nonno era solito trascrivere le sue improvvisazioni sulle composizioni di Bach. Il mio lavoro a partire dai tre anni è stato quello di cambiare le pagine degli spartiti quando si esercitavano, di solito otto battute prima. Ai miei nonni e a mia madre piaceva il jazz specie Art Tatum, Duke Ellington e Count Basie ed in seguito Miles Davis. Ho ascoltato Count Basie con Joe Williams durante un concerto a Londra quando avevo undici anni. Sebbene fossi affascinato dal batterista Sonny Payne ne venni via con le linee di basso impresse nella testa: così seppi da quel momento che avrei suonato il basso. Presi alcune lezioni sul contrabbasso, e passai all’elettrico all’età di quattordici anni, quando era relativamente uno strumento nuovo. Circa quindici anni fa presi le misure per dei tappi auricolari personalizzati che avevano una risposta in frequenza piatta e ricevetti una nota dal costruttore in cui dichiarava di non poter garantire una risposta piatta nel mio caso perché avevo dei canali insolitamente profondi che accentuavano la risposta del basso. Credo che ci fosse una ragione per cui fossi attratto da quello strumento. A quanto pare avverto molto di più le basse frequenze rispetto alla maggior parte delle persone! |

|

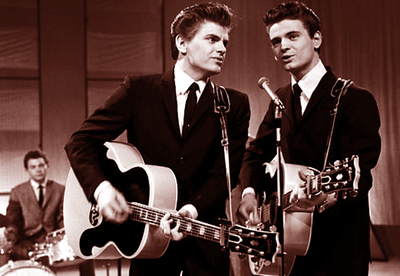

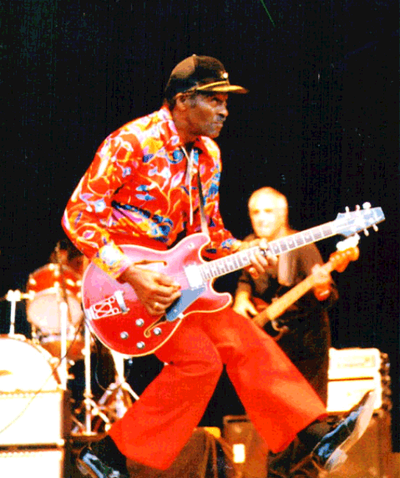

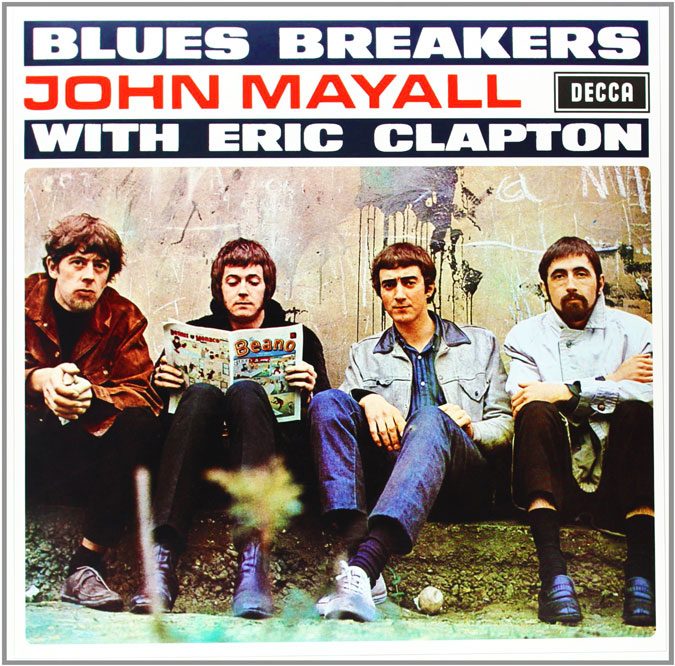

BMF: What were your first music influences, in general, and as regards bass? Who are the bassists by whom you got inspired? I was also listening to all the American pop music at that time. I particularly liked the Everly Brothers, Elvis, Buddy Holly, and all the early rockers. I was also a fan of The Shadows, who had some of the first Fender instruments in the UK. I had some lessons on upright bass, and took up electric bass at the age of 14 in 1962, when it was a relatively new instrument. By then I had discovered Chicago blues and I was also listening to a lot of jazz. I was a big fan of Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley and it was a thrill to play with both of them decades later! My favourite jazz bassist/composer was Charles Mingus. I looked older than 14 and was able to start going to clubs and hearing the London bands. By the time I was 16 I was playing some gigs, mostly blues and some jazz. The London jazz musicians at this time were crossing over into American blues and R&B. Those records were hard to come by at that time, so many of the jazz musicians were getting gigs on the ocean liners to the USA and bringing back the records. Alexis Korner and Chris Barber were two of the first London musicians to assemble bands with mostly jazz musicians playing blues. The music started getting a club following, and right behind them came bands led by Graham Bond, Cyril Davis, John Mayall (with Eric Clapton, John McVie & Mick Fleetwood), Manfred Mann, The Who, The Yardbirds,The Pretty Things, Long John Baldry with Rod Stewart, The Rolling Stones, The Downliners Sect, Zoot Money, Georgie Fame, The Ram Jam Band and a few others. |

BMF: Quali sono state le tue prime influenze musicali? E quali bassisti sono stati per te fonte di ispirazione? SY: Ho ascoltato anche molto pop americano per un periodo. In particolare mi piacevano gli Everly Brothers, Elvis, Buddy Holly, e tutti i primi rockers. Ero anche un fan degli Shadows, che disponevano di alcuni dei primi Fender nel Regno Unito. Dopo aver preso alcune lezioni di contrabbasso passai al basso elettrico all’età di quattordici anni nel 1962 quando era relativamente uno strumento nuovo. Nel frattempo avevo scoperto il Chicago blues e ascoltavo molto jazz. Ero un grande fan di Chuck Berry e Bo Diddley ed è stato emozionante suonare insieme a loro decenni più tardi! Il mio bassista/compositore jazz preferito era Charles Mingus. Sembravo più grande dei miei quattordici anni così ebbi la possibilità di iniziare a frequentare i club e ascoltare le band di Londra. Compiuti i sedici anni suonavo ad alcuni concerti, soprattutto blues e un po’ di jazz. I musicisti jazz londinesi attraversavano l’American blues e l’R&B. I dischi di allora erano difficili da reperire così molti dei musicisti jazz venivano ingaggiati per concerti sulle navi da crociera alla volta degli Stati Uniti e portavano con sé i dischi al ritorno. Alexis Korner e Chris Barber furono due dei primi musicisti ad unire gruppi in cui la maggior parte dei musicisti suonavano blues. La musica iniziava ad essere seguita da un club, e proprio dietro di loro si susseguirono band guidate da Graham Bond, Cyril Davies, John Mayall (con Eric Clapton, John McVie & Mick Fleetwood), Manfred Mann, The Who, The Yardbirds,The Pretty Things, Long John Baldry con Rod Stewart, The Rolling Stones, The Downliners Sect, Zoot Money, Georgie Fame, The Ram Jam Band e qualcun altro. |

|

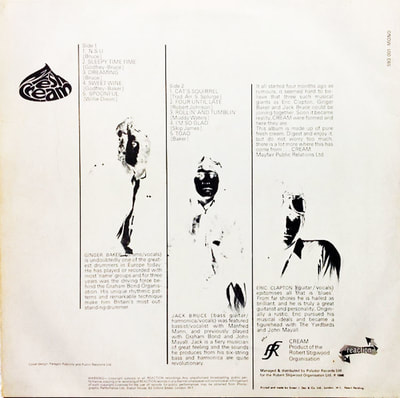

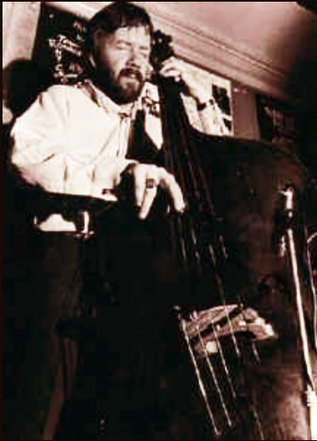

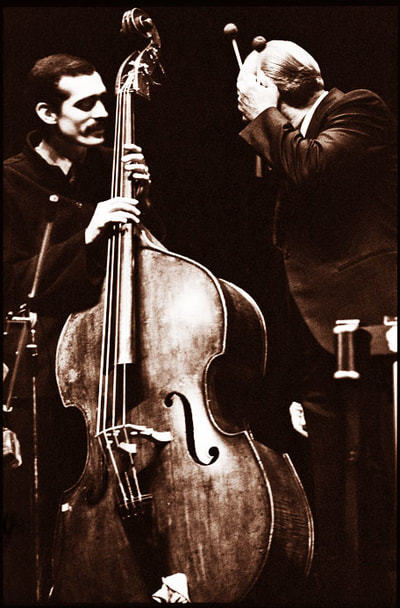

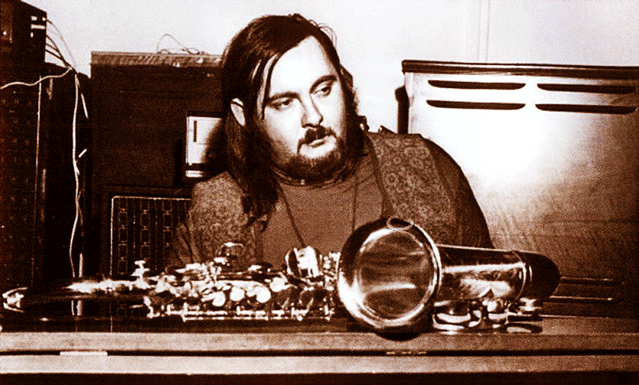

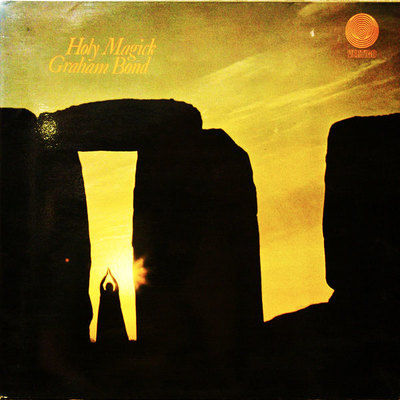

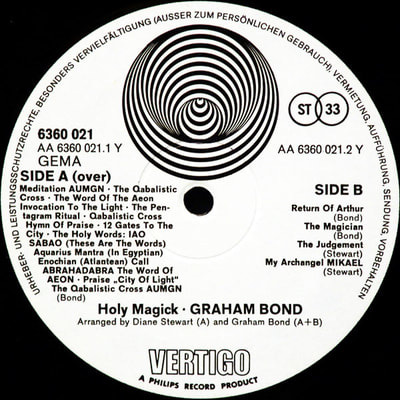

The bands I heard most often when I was starting to play were Alexis Korner and the two offshoot bands from his band. Cyril Davis was a harmonica player who had spent some time in Chicago and split from Alexis’s band to play less jazzy blues. He put together some of London’s best rock players ( I think mostly from Screaming Lord Sutch’s band. The other offshoot band was Graham Bond’s band which had a huge influence on me. Graham was a leading cutting edge alto sax player, but he bought one of the first Hammond B3 organs in the UK and sang. He had Ginger Baker on drums, Jack Bruce on bass, and, at first, John McLaughlin on guitar, later replaced by Dick Heckstall-Smith on tenor sax. This was an amazing band and influences me to this day. I heard all these London bands regularly from 1962 to 1967. I was more partial to the more jazz influenced groups. The jazz players of that time realized that they could work more if they simply played jazz over American soul, R&B and blues grooves so there were some fine players in some of these bands. Nobody cared about copying the original records. They threw a bunch of styles into the pot and came up with some original sounds. Alexis would mix Mingus with Muddy Waters! Between 1964 – 1966 the London club scene was thriving. I would often leave the house with my bass on Thursday night and stay out until Sunday morning. There were folk music clubs, rock clubs, blues clubs and jazz clubs, some of which were open all night. After regular club hours, many of the musicians would move around from club to club and sit in with each other. The mixing of backgrounds and styles led to some interesting music. A good example of one of the many bands that came out of this is Pentangle which combined folk and jazz with Danny Thompson on bass. |

Le band che ascoltavo di più - quando iniziai a suonare - erano gli Alexis Korner e le due ramificazioni derivanti dalla loro formazione. Cyril Davies era un suonatore di armonica che aveva trascorso un po’ di tempo a Chicago e si separò dalla Band di Alexis per suonare meno il jazzy blues. Mise insieme alcuni dei migiori musicisti rock, credo la maggior parte provenienti dalla band Screaming Lord Sutch (and the Savages). Una nuova ramificazione fu la band di Graham Bond che ha esercitato un’influenza enorme su di me. Graham era un sassofonista contralto leader nell’avanguardia, ma comprò uno dei primi organi Hammond B3 nel Regno Unito e iniziò a cantare. C’erano con lui Ginger Baker alla batteria, Jack Bruce al basso e in un primo momento John McLaughlin alla chitarra più tardi sostituito da Dick Heckstall-Smith al sax tenore. Fu una band straordinaria che continua ad ispirarmi tutt’ora. Ascoltai tutte queste formazioni con una certa regolarità a Londra dal 1962 al 1967. Ero più interessato ai gruppi orientati al jazz. I musicisti di quell’area in quel periodo si resero conto che avrebbero lavorato di più suonando del jazz su un groove del genere soul americano, R&B e blues, perciò c’erano sempre dei musicisti raffinati in alcune di quelle line-up. A nessuno importava replicare i dischi originali. Lanciavano nel calderone un mucchio di stili e ideavano un sound innovativo. Alexis arrivò a mixare Mingus con Muddy Waters! Tra il 1964 ed il 1966 la scena dei club londinesi era fiorente. Lasciavo spesso casa con il mio basso al seguito il giovedì sera stando fuori fino alla domenica mattina. C’erano club di genere folk, blues e jazz alcuni dei quali rimanevano aperti tutta la notte. Finito l’orario normale molti dei musicisti si spostavano da un club all’altro e si sedevano allo stesso tavolo. La commistione di background e stili ha prodotto musica interessante. Un buon esempio di una delle numerose band che venne fuori da questo contesto furono i Pentagle che coniugavano folk e jazz con Danny Thompson al basso. |

|

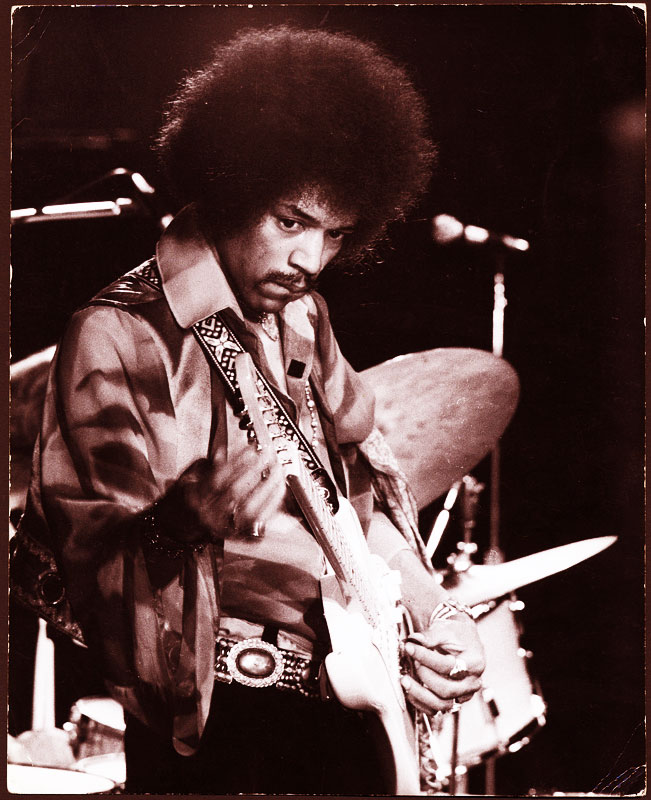

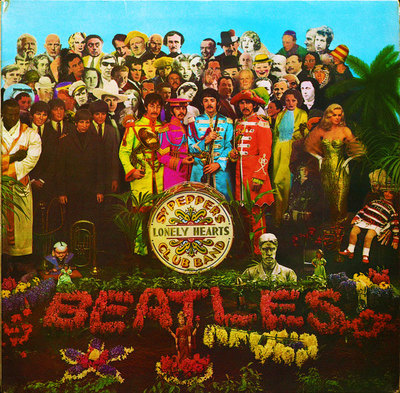

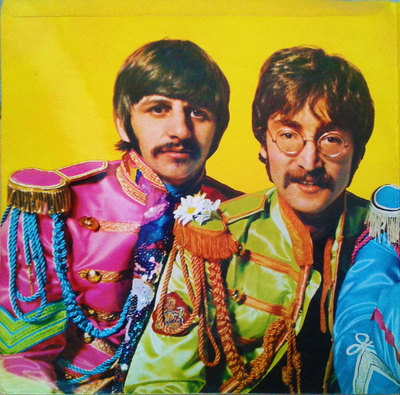

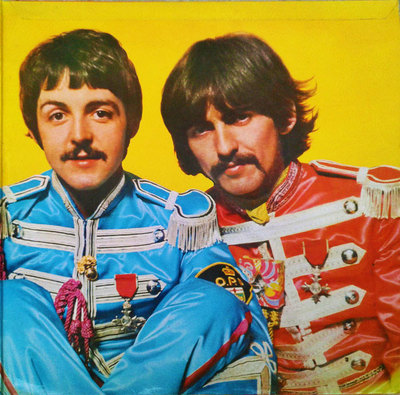

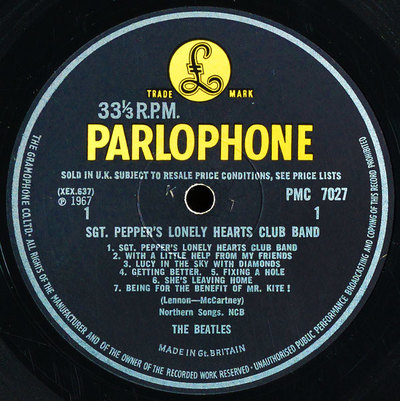

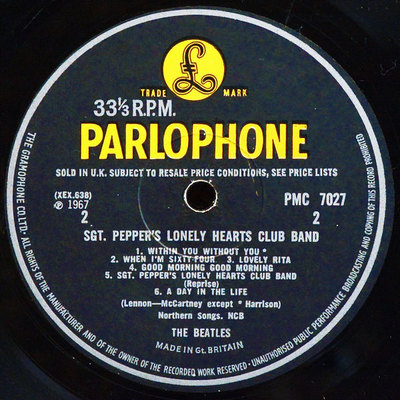

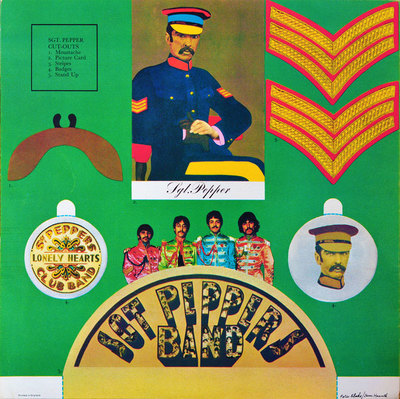

In 1966 I turned 18 which meant I could legally leave the country to work. I got a gig with an English variety band playing on the US airbase in Izmir, Turkey for a year and then the Greek island of Crete for 3 months. This meant that I got deeply exposed to American blues, jazz, R&B and country music that was not being heard in the UK at that time. I also played regularly with Turkish folk and classical musicians. The variety band played 6 to 8 hours 6 days a week on the air base, and then I would go and play with the Turks at their clubs! During this time Eric Clapton’s first album with John Mayall came out and then later Cream’s first record was released. I had them sent to me from England. When I returned to the UK in 1968 the music scene was in full boil. I was stunned to hear Jimi Hendrix and the Cream on TV and radio. This music had been confined to clubs before and was now breaking out. The London clubs were bigger and more eclectic. Psychedelia had hit the clubs, and the melding of musical styles was rampant. This was real fusion music. The Sergeant Pepper album was out. I had always liked The Beatles records but pop music wasn’t really my thing. This album, however, blew me away. I hooked up with an old friend, John Lee. I had met Jon when I took jazz theory classes at the age of 14-16. He was a trombonist who had played on the Sergeant Pepper album. |

Nel 1966 divenni maggiorenne il che significava poter lasciare il paese legalmente per lavorare. Feci un concerto con una varietà di band suonando sulla base aerea statunitense a Izmir in Turchia per un anno e dopo sull’isola di Creta in Grecia per tre mesi. Questo implicò l’essere continuamente esposto al blues americano, al jazz, R&B e alla musica country che non veniva ascoltata nel Regno Unito in quel periodo. Inoltre suonavo regolarmente con musicisti turchi di musica classica e folk. Le varie band provavano dalle sei alle otto ore al giorno sei giorni la settimana sulla base aerea, perciò in seguito avrei suonato con i turchi ai loro club! Durante quella fase uscì il primo album di Eric Clapton con John Mayall e più tardi il primo disco dei Cream. Me li dovetti far spedire dall’Inghilterra. Quando ritornai nel Regno Unito nel 1968 la scena musicale era in piena ebollizione. Rimasi sbalordito nell’ascoltare Jimi Hendrix ed i Cream in Tv e per la radio. Quella musica rimase confinata nei club prima di esplodere. I club di Londra erano più grandi e più eclettici. La Psichedelia era penetrata lì e la fusione degli stili era dilagante. Si trattava di vera e propria fusion. L’album Sergeant Pepper era uscito. Mi piacevano i dischi dei Beatles ma la musica pop non faceva del tutto per me. Quell’album tuttavia mi fece impazzire. Uscii con un vecchio amico, John Lee. Lo conobbi quando prendevo lezioni di teoria jazz all’età di 14-16 anni. Era un trombonista che aveva suonato sull’album The Sergeant Peppers. |

|

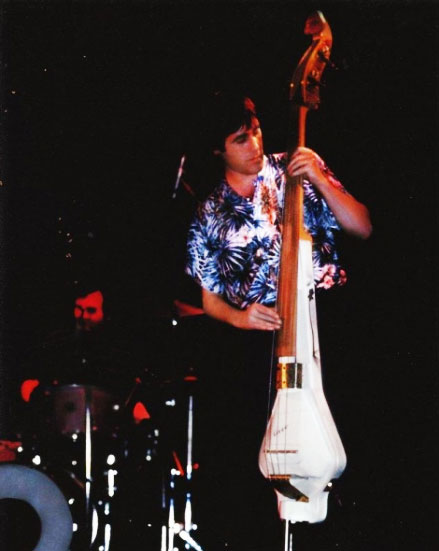

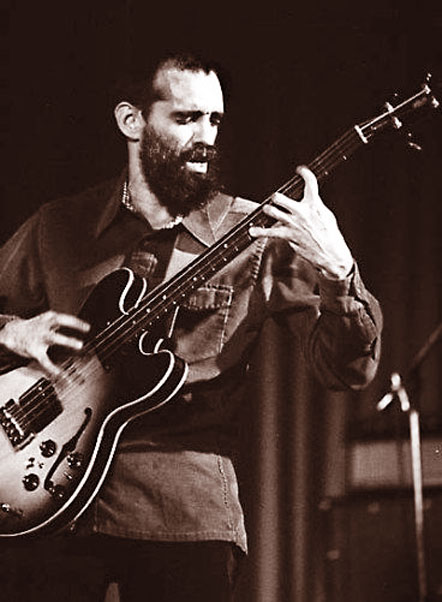

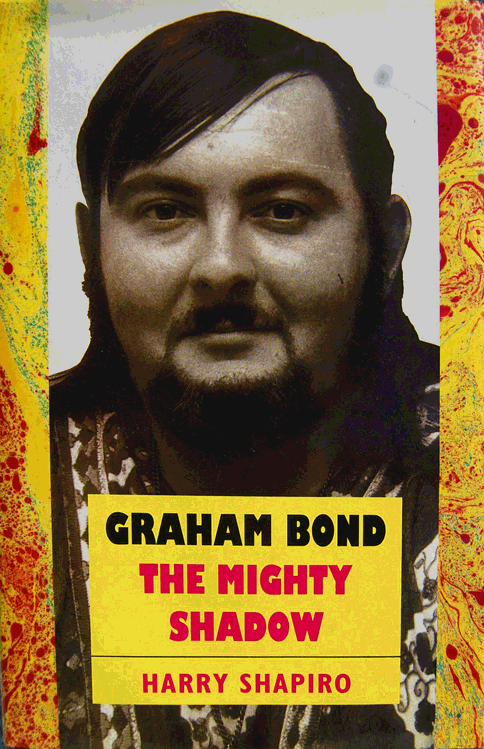

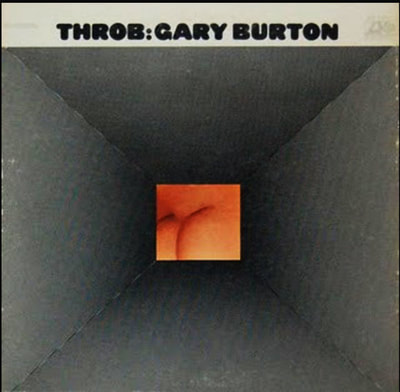

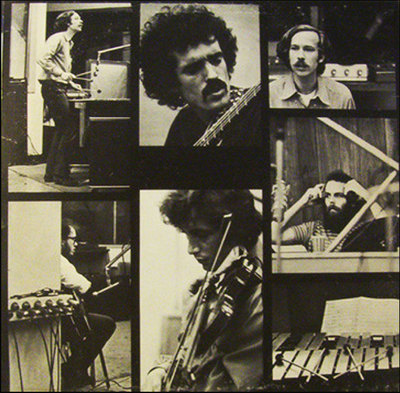

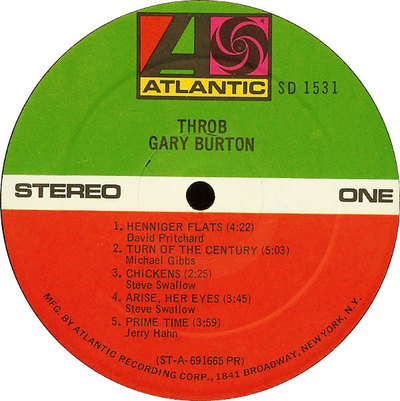

The club scene was so open to anything that we formed a trombone/bass duo and were able to get gigs! Graham Bond heard us and we were briefly hired to play in his band, but Graham left to spend a year in the US. I had a long and close relationship with Graham until his tragic death. For more on Graham, get hold of the almost impossible to find book ”Graham Bond, The Mighty Shadow” by Harry Shapiro. I also landed steady work playing on TV jingles as there were very few electric bassists who could read music and play many styles at that time. This meant that I was working with older musicians who showed me a lot about rhythm section playing. They also stressed the importance in studio work of being able to comprehend and play a piece of music very quickly. I gained a lot of experience doing this. This was still a transitional period between upright and electric bass. I was drawn more towards upright players and attempted to translate uptight styles to electric. I even removed the frets from my Gibson EBO at one point but it sounded awful! The primary bassists I went to see live in London were Jack Bruce, Danny Thompson and Spike Heatley. Jack was playing upright with Graham Bond when the band started. I could barely hear him. John McLaughlin was playing guitar in the band then. I would stand a few feet from Jack’s bass. He soon bought a cheap bass guitar. I was at the 100 club in London when that bass shorted out and burnt Jack’s left hand badly. He went to the hospital and returned with his hand bandaged and finished the gig between swigs from a whiskey bottle! After that he bought his Fender Bass VI. I also met Steve Swallow at the Montreux Jazz Festival in 1969 when he was making the transition from upright to electric with Gary Burton and I introduced him to Rotosound roundwound strings which were not available in the US at the time. |

La scena dei club era aperta a qualsiasi cosa a tal punto da arrivare a costituire un duo basso/trombone e fummo in grado di fare serate! Graham Bond ci ascoltò e fummo rapidamente ingaggiati a suonare nella sua band, ma Graham partì per trascorrere un anno negli Stati Uniti. Strinsi una lunga e profonda amicizia con Graham fino alla sua tragica fine. Per saperne di più su di lui provate a reperire l’introvabile libro “Graham Bond, The Mighty Shadow” di Harry Shapiro. Riuscii ad ottenere un lavoro fisso suonando sui jingles alla Tv dal momento che c’erano pochi bassisti elettrici che sapevano leggere la musica e suonare molti stili in quel periodo. Il che significava lavorare con musicisti più avanti con l’età che mi svelavano un mucchio di cose riguardo al suonare in una sezione ritmica. Inoltre rimarcavano l’importanza del lavoro in studio per essere in grado di comprendere e suonare un pezzo molto velocemente. Ho guadagnato molta esperienza sul campo. Si trattava ancora di una fase di transizione tra il contrabbasso ed il basso elettrico. Ero più immerso nei contrabbassisti e intento ad adattare stili rigidi all’elettrico. Rimossi persino i tasti dal mio Gibson EBO ad un certo punto ma aveva un sound terribile! I primi bassisti che andai a vedere dal vivo a Londra furono Jack Bruce, Danny Thompson e Spike Heatley. Jack suonava il contrabbasso con Graham Bond quando la band fu fondata. Riuscivo a malapena ad ascoltarlo. John Mclaughlin avrebbe suonato la chitarra nella band in seguito. Mi trovavo a pochi passi dal basso di Jack. Presto acquistò un basso economico. Mi trovavo al club 100 di Londra quando lo strumento andò in corto circuito e bruciò gravemente la mano sinistra di Jack. Andò all’ospedale e ritornò con la sua mano bendata e finì il concerto tra un sorso e l’altro dalla sua bottiglia di whiskey! Dopo quell’incidente acquistò il suo Fender Bass VI. Incontrai pure Steve Swallow al Montreux Jazz Festival nel 1969 nel periodo in cui passava dal contrabbasso al basso elettrico con Gary Burton e così lo introdussi alle corde roundwound della Rotosound che non erano disponibili negli Stati Uniti all’epoca. |

|

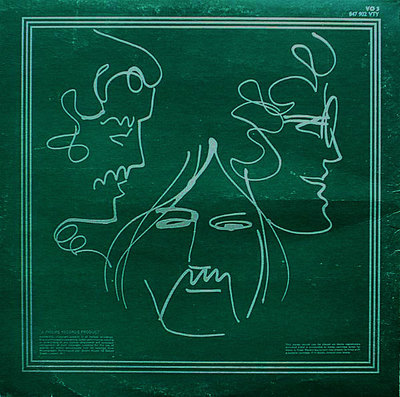

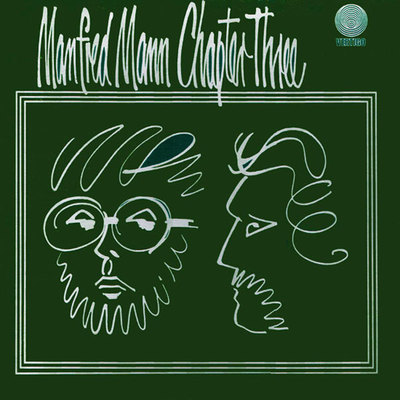

I was also listening to a lot of Caribbean music (blue beat, ska, early reggae) and jamming with the West Indian and African musicians in London. My early bass influences include Charles Mingus, Paul Chambers, Ray Brown, Steve Swallow, Jack Bruce, Danny Thompson, Spike Heatley, Jet Harris and Cliff Burton. In 1970 I did my first US tour with progressive jazz rock band Manfred Mann Chapter 3 and was heavily influenced by the great R&B bassists such as James Jamerson, Jerry Jemmott, Chuck Rainey, Gordon Edwards, Tommy Cogbill, Harvey Brooks and David Hood. In London my favourite bassists through the 70’s were Alan Spenner, Phil Chen, Alan Gorrie and Kuma Harada. |

Ascoltavo anche molta musica caraibica (blue beat, ska, il primo reggae) e mi esibivo con i musicisti delle indie occidentali e africani a Londra. Le mie inflenze iniziali annoveravano Charles Mingus, Paul Chambers, Ray Brown, Steve Swallow, Jack Bruce, Danny Thompson, Spike Heatley, Jet Harris, Cliff Burton. Nel 1970 feci il mio primo tour negli Stati Uniti con la band prog jazz rock Manfred Mann Chapter 3 e fui profondamente influenzato dai grandi bassisti R&B come James Jamerson, Jerry Jemmott, Chuck Rainey, Gordon Edwards, Tommy Cogbill, Harvey Brooks, & David Hood. A Londra I miei bassisti preferiti negli anni ’70 erano Alan Spenner, Phil Chen, Alan Gorrie & Kuma Harada. |

|

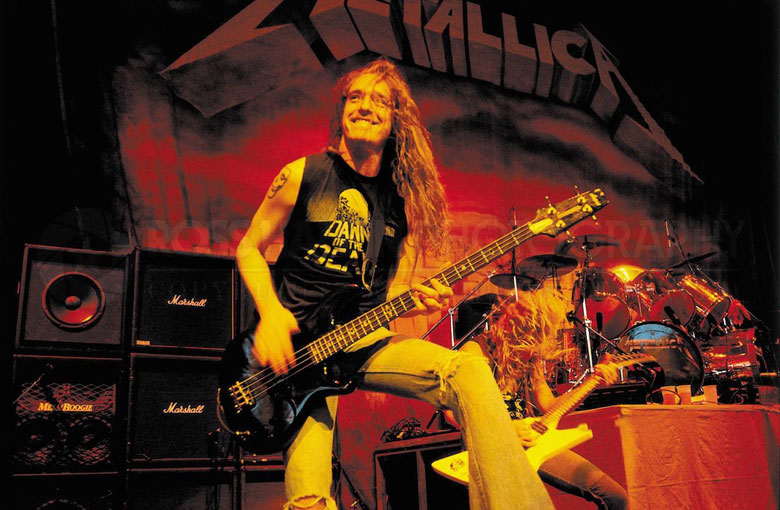

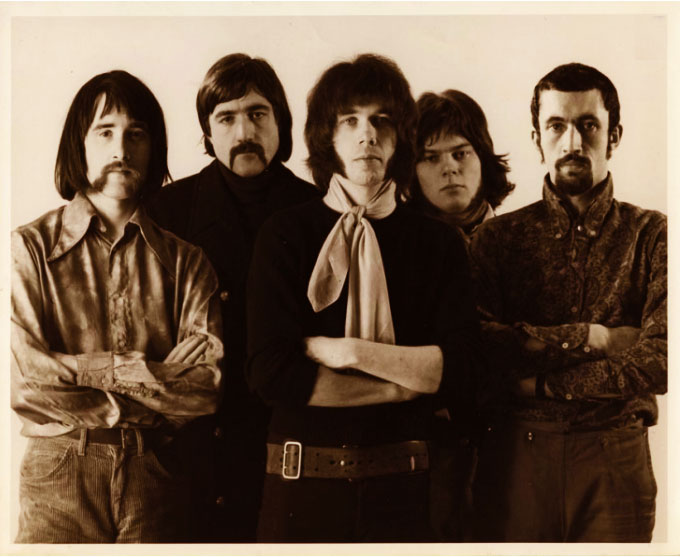

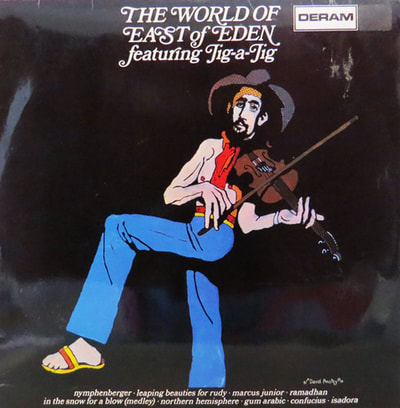

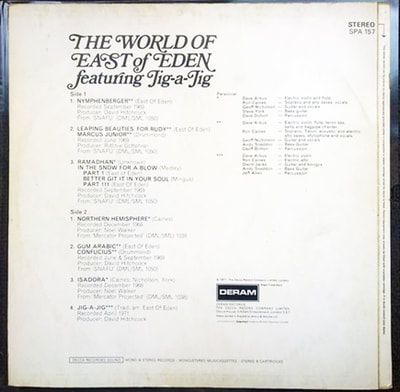

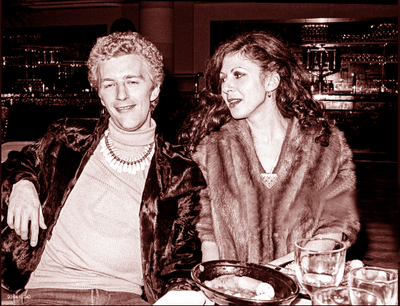

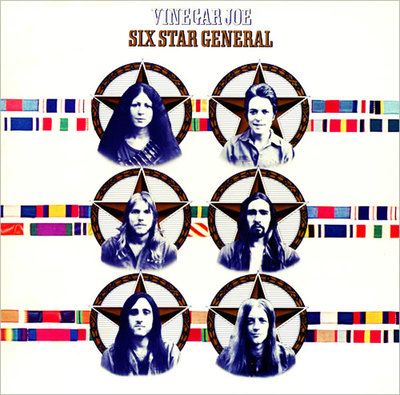

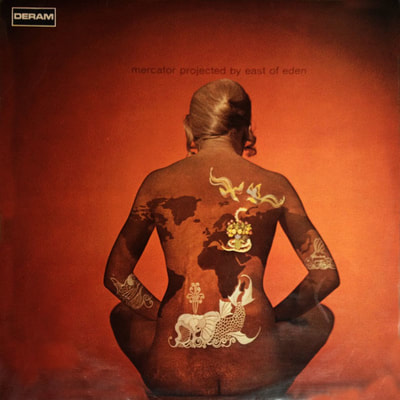

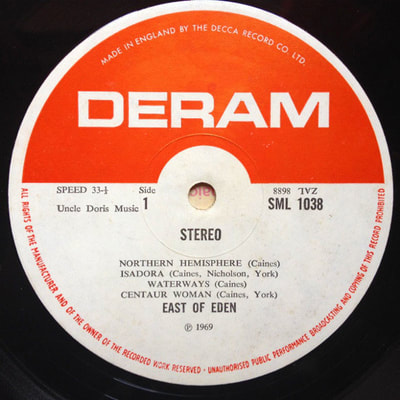

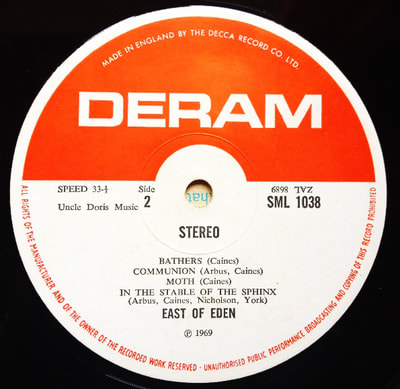

BMF: In your long and great career you have been the bassist of two key groups, East of Eden and Vinegar Joe. What’s your memory of those important experiences? I auditioned for East Of Eden in 1968, not long after my return from playing US airbases in Turkey and Greece for 18 months. I had been listening to American music while working there, especially BB King, James Brown, Jackie Wilson, Junior Walker and all the Motown artists, and also a lot of US Country music such as Buck Owens and Merle Haggard. I had collected about 70 LP’s that were not available in the UK but most of them were stolen at Munich train station on my way home to the UK! I had also been exposed to Turkish music and had jammed with Turkish musicians. East of Eden’s art rock was very alien to me but I liked the guys in the band and they were totally open to what I had to offer. I am still in touch with guitarist Geoff Nicholson 50 years later! I was only with the band for about a year during which time we recorded their first album and toured around Europe. Manfred Mann drummer/ pianist Mike Hugg heard me in a London club and Manfred recruited me as the bassist for their new progressive jazz rock band Manfred Mann Chapter 3. At first I turned them down as I was happy with East Of Eden but East of Eden’s manger told me to go with Manfred. In retrospect I think he knew that the band was going to get stiffed financially and he was trying to spare me from that. East of Eden had a hit with “Jig A Jig” shortly after I left and we never saw any royalties. Only recently did we start seeing a small amount thanks Geoff Nicholson’s efforts. |

BMF: Nella tua lunga e grande carriera sei stato il bassista di due formazioni cardine, East Of Eden e Vinegar Joe. Come ricordi queste due fondamentali esperienze? SY: Feci un’audizione per gli East of Eden nel 1968 non molto dopo il mio ritorno dalle basi aeree statunitensi in Turchia ed in Grecia in cui avevo suonato per 18 mesi. Ascoltavo musica americana mentre lavoravo lì, in particolare BB King, James Brown, Jackie Wilson, Junior Walker e tutti gli artisti della Motown e pure molta musica Country statunitense come Buck Owens e Merle Haggard. Ho collezionato quasi 70 LP che non erano reperibili nel Regno Unito ma molti di loro mi vennero rubati alla stazione di Monaco lungo la strada di ritorno in Gran Bretagna. Ho avuto modo di ascoltare anche la musica turca e ho improvvisato con alcuni musicisti della stessa nazionalità. L’art rock degli East of Eden mi era davvero estraneo, ma mi piacevano i ragazzi della band ed erano totalmente ricettivi verso quello che io avevo da offrire. Sono ancora in contatto con il chitarrista Geoff Nicholson anche dopo 50 anni! Rimasi con quella band per circa un anno durante il quale registrammo il loro primo album e andammo in tour per l’Europa. Il pianista Manfred Mann ed il batterista Mike Hugg mi sentirono in un club di Londra, così Manfred mi reclutò come bassista per la loro nuova band prog-jazz-rock, i Manfred Mann Chapter 3. All’inizio ero restìo dal momento che ero felice con gli East Of Eden ma il manager mi disse di andare con i Manfred. Col senno di poi credo che lui sapesse che la band versava in cattive acque dal punto di vista finanziario, dunque lui cercava di risparmiarmi quella china. East of Eden ebbe successo con “Jig A Jig” poco dopo aver lasciato e non vedemmo nessuna royalties. Solo di recente abbiamo iniziato a vedere qualcosa grazie agli sforzi di Geoff Nicholson. |

|

|

|

|

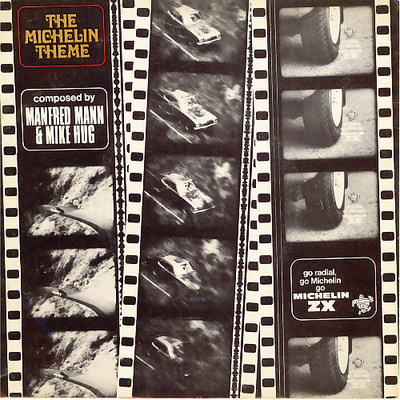

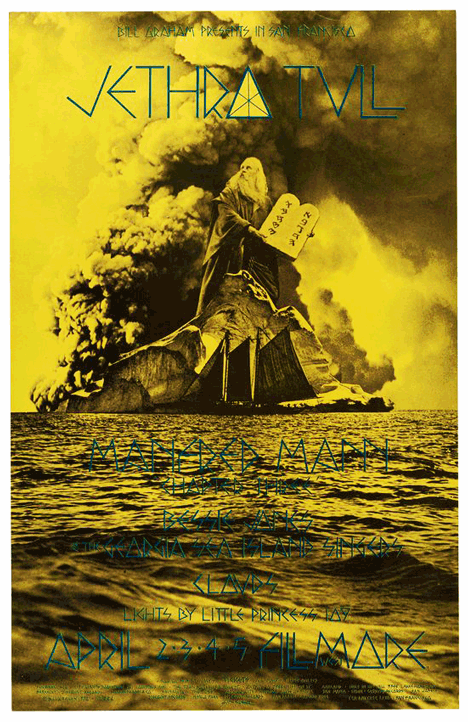

Working with Manfred was more significant than my tenure with E of E. When I joined Manfred I was already doing several jingle sessions a week. At the time there were few electric bassists who could read and work fast in the studio so I was getting a lot of calls. This doubled with Manfred as he and Mike Hugg were writing and producing a lot of jingles. Here is one we recorded for Michelin. I recall this session well. We ran through it and recorded it in one take. I had the chart laid out on a speaker cabinet and when we started recording I saw that the last page was on top of an ashtray with a cigarette burning a hole in it. I had to try and memorize the last page while reading the rest of the chart! Luckily there was nothing too tricky at the end! The band only lasted two years. During that time we did two albums and a US tour. I was only 21 and I learnt from Manfred & Mike who were already established and experienced. The US tour was an eye opener for me. Our first date was three days at Fillmore West in San Francisco. Also on the bill were Boz Scaggs, The Steve Miller Band, and Janice Joplin. The standard of music I heard both live and on the radio there made me feel like I should go back home and practice! I was playing very freely with Manfred. There was no guitar in the band and they wanted me to fill the space and play busy. After that band folded I decided I needed to play with much more discipline and I immersed myself in the R&B music I had discovered in the US. |

Lavorare con i Manfred fu più importante del mio mandato con gli East of Eden. Quando mi unii alla band già facevo diverse registrazioni di jingles alla settimana. All’epoca c’erano pochi bassisti elettrici che sapevano leggere la musica e che erano rapidi in studio perciò ricevevo moltissime richieste. Queste raddoppiarono con i Manfred dal momento che lui e Mike Hugg stavano componendo e producendo un mucchio di jingles. Qui ce ne è uno che incidemmo per la Michelin. Mi ricordo bene di questa sessione. Ci buttammo a capofitto e la registrammo in un unico take. Avevo il mio spartito steso su di uno speaker cabinet e quando iniziammo ad incidere mi accorsi che l’ultima pagina si trovava su di un posacenere con una sigaretta che stava facendo un buco nel mezzo. Così ho duvuto provare a memorizzare quell’ultima pagina mentre leggevo il resto dello spartito! Per mia fortuna non c’era niente di troppo complicato verso la conclusione! La band durò solo due anni. Durante quel periodo abbiamo fatto due album ed un tour per gli Stati Uniti. Avevo solo 21 anni e mi resi conto che Manfred&Mike erano già consolidati e navigati. Il tour statunitense fu una rivelazione per me. Il nostro primo show fu uno spettacolo di tre giorni al Fillmore West a San Francisco. Inoltre nella lista c’erano Scaggs, The Steve Miller Band, e Janice Joplin. Lo standard della musica che ascoltai lì sia dal vivo che per radio mi fece sentire come se dovessi tornare a casa e mettermi a provare! Suonavo molto spontaneamente con i Manfred. Non c’era nessuna chitarra nella band e volevano che io riempissi lo spazio e che suonassi in maniera continuativa. Dopo lo scioglimento del gruppo mi decisi a suonare con più disciplina così mi immersi nell’R&B che scoprii negli USA. |

|

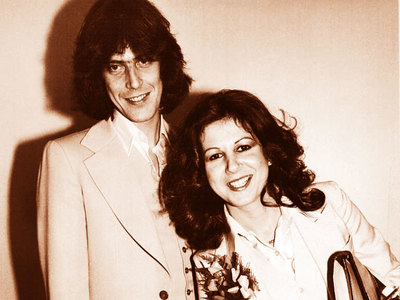

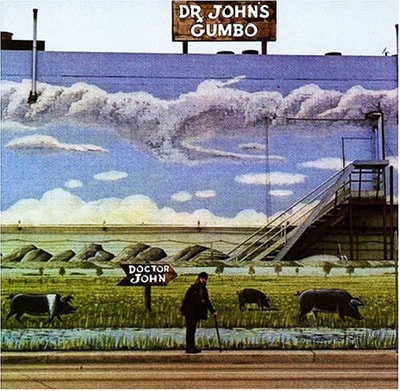

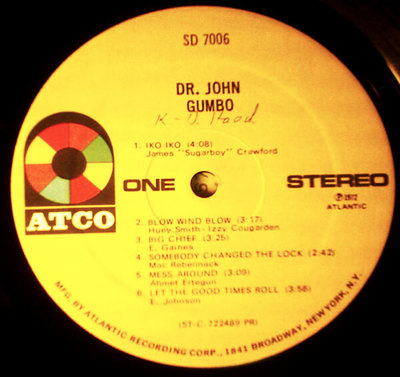

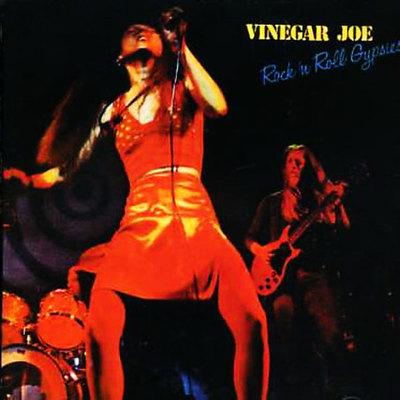

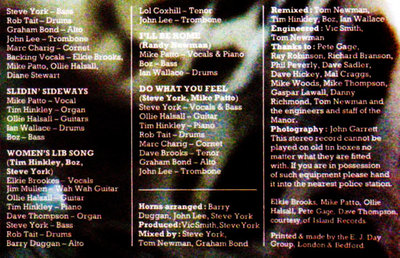

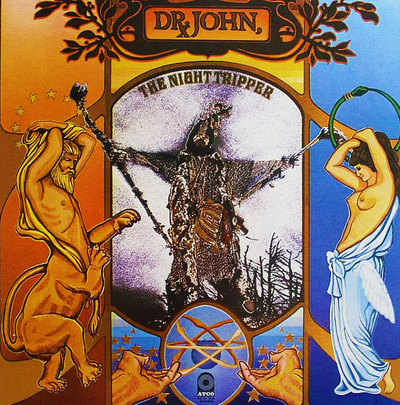

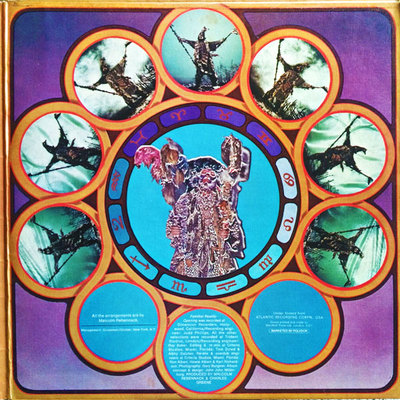

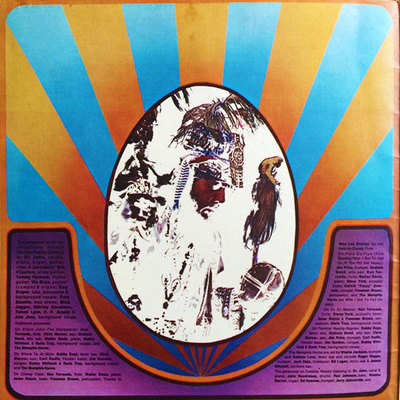

One of my favourite London bands at the time was Dada. It was a ten piece band signed to Atlantic records. The band was very groove orientated and tightly arranged but also played with a lot of freedom. Phil Chen had played bass on their album but did not want to tour with the band. I heard that they were auditioning bassists and I got selected. It was exactly what I was looking for musically at the time. We did a US tour. When we returned to the UK we played at Ronnie Scott’s jazz club. Atlantic Records boss Ahmet Ertegun came to see us. The next day I was summoned to Ahmet’s hotel suite along with Elkie Brooks, her husband guitarist and Dada bandleader Pete Gage, and Robert Palmer. Ahmet explained that Atlantic could not keep financing a ten piece band and that he wanted the four of us to find a new drummer and keyboard player and form a new band. Chris Blackwell of Island Records was at the meeting. The deal was that we would be signed to Atlantic in the US and to Island in Europe. We recorded the first album with the four core members. Tim Hinckley and Dave Thompson played keys, and the drummers were Conrad Isidore from Manfred’s band and Rob Tait. We had to wait for a few months for the album release. I decided to visit the US. I had recorded with Dr John in London and he invited me to play on his next album in LA. When I arrived in LA Mac ( Dr John) told me that producer Jerry Wexler had decided that the record should be pure New Orleans R&B with New Orleans musicians and that he could not use me, but that I was welcome to stay with him and attend the sessions. The album was the classic “Gumbo” Mac would stay up all night listening to hundreds of tapes of New Orleans classics that Jerry Wexler had brought and coming up with his own arrangements , then going straight to the studio and recording them. For me this was a crash course in Nawlin’s music, or as Mac would say “an edumacation”! |

Una della mie band preferite di Londra del tempo erano i Dada. Si trattava di una band di dieci elementi che firmò con la Atlantic Records. Era orientata ad un sound molto groove e con arrangiamenti rigorosi ma riusciva a suonare con molta libertà. Phil Chen ha suonato il basso sui loro album ma non voleva esibirsi in tour. Venni a sapere che erano alla ricerca di un bassista così venni scelto. Musicalmente era esattamente quello che stavo cercando in quel periodo. Facemmo un tour negli Stati Uniti. Quando ritornammo nel Regno Unito ci esibimmo al Ronnie Scott's jazz club. Il capo della Atlantic Records, Ahmet Ertegun, venne a vederci. Il giorno seguente fui convocato nella suite dell’hotel di Ahmet insieme ad Elkie Brooks, suo marito chitarrista ed il leader della band Pete Gage e Robert Palmer. Ahmet ci spiegò che la Atlantic non avrebbe potuto finanziare una band di dieci membri e voleva che quattro di noi cercassero un nuovo batterista e un tastierista per formare un nuovo gruppo. Chris Blackwell della Island Records era presente all’incontro. Il patto era che noi avremmo dovuto firmare un contratto con la Atlantic negli Stati Uniti e con la Island in Europa. Registrammo il primo album con il nucleo di 4 elementi della band. Tim Hinckley e Dave Thompson suonavano le tastiere ed i batteristi sarebbero stati Conrad Isidore della Manfred band e Rob Tait. Dovemmo aspettare pochi mesi prima dell’uscita dell’album. Decisi di visitare gli Stati Uniti. Avevo già inciso con Dr John a Londra, così lui mi invitò a suonare nel suo album di prossima uscita a Los Angeles. Quando arrivai, Mac (Dr John) mi disse che il produttore Jerry Wexler aveva deciso che il disco avrebbe dovuto essere di un puro R&B di New Orleans con musicisti di quella zona; perciò lui non avrebbe più potuto servirsi di me ma ero comunque il benvenuto e libero di assistere alle prove. L’album era il classico “Gumbo”, Mac sarebbe rimasto tutta la notte ad ascoltare centinaia di registrazioni di classici di New Orleans che Jerry Wexler aveva portato e tirò fuori alcuni arrangiamenti, poi andò dritto in studio e li incise. Per me quello fu un corso intensivo di musica di Nawlin’ (di New Orleans, ndr), o come Mac avrebbe detto una “infarinatura”! |

|

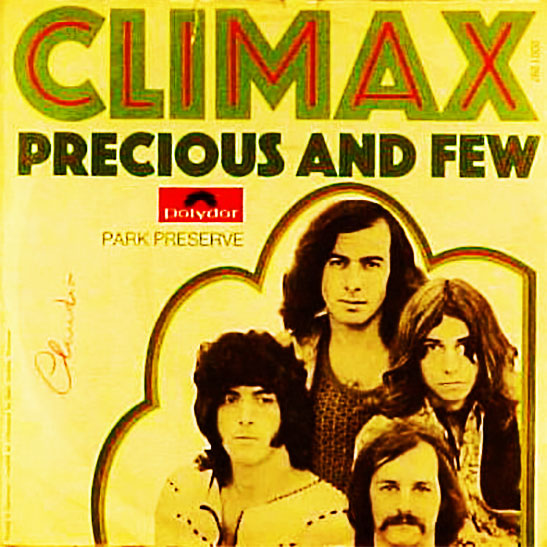

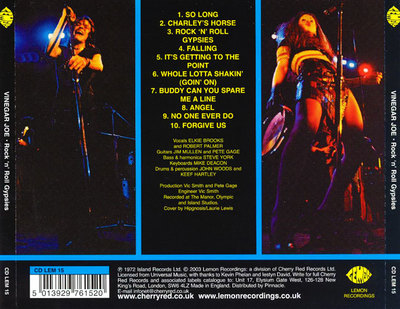

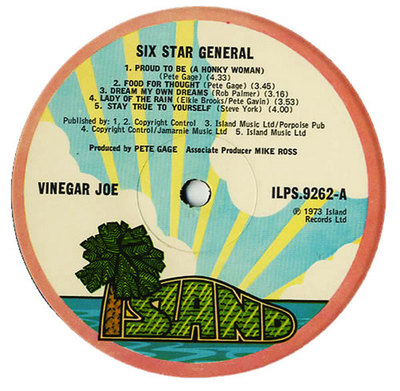

I was hitch hiking on the Pacific Coast highway when a car pulled up. It was drummer who recognized me. He had driven from Florida to audition with a band whose record had just entered the charts. They were looking for a bassist and he invited me to audition with him. I got the gig and toured with band for nine months during which time the record reached number 2 in the US charts. It was a ballad called “Precious and Few” by Climax. I had to return to the UK because US immigration would no longer renew my visa. By then the first Vinegar Joe album had been released. Elkie and Pete Gage had contacted me. They were planning to replace the keyboard player and drummer and invited me to rejoin on bass. We had always admired Pete Gavin’s drumming with Head, Hands & Feet . That band was breaking up and Pete had agreed to join Vinegar Joe. We recorded the second album “Rock & Roll Gypsies” with Keef Hartley on drums. Guitarist Jim Mullen also joined at that time. The new keyboard player was Mike Deacon. Jim left after our US tour in 1973. We recorded the “Six Star General” album with Elkie, Robert Palmer, Pete Gage, myself and Pete Gavin . This is my favourite of the three albums. It was released and the first pressing sold out fast, but the vinyl crisis hit and there was a long delay before the next pressing. Then Robert announced that he was leaving for a solo career. It turned out that Chris Blackwell and Robert had simply been using the band to prime Robert to go solo. We had intended to carry on without him and recorded two tracks with Elkie. Island released a few copies in Holland but pulled it when Island decided to no longer support the band without Robert. We disbanded at that point. Here are clips “lost” tracks. “Sweet Nothings” (This was the only time I played bass with a pick!) & “Rescue Me” |

Mi misi a fare l’autostop lungo la costa del pacifico quando un’auto mi fece salire a bordo. Era un batterista che mi riconobbe. Aveva guidato dalla Florida per un provino con una band il cui disco era entrato nelle classifiche. Stavano cercando un bassista così mi invitò all’audizione con lui. Ottenni l’ingaggio e andai in Tour con la band per nove mesi durante i quali il disco raggiunse la seconda posizione nella classifica statunitense. Si trattava di una ballad intitolata “Precious and Few” dei Clymax. Dovei fare ritorno nel Regno Unito dal momento che l’Ufficio Immigrazione non riconosceva più la mia Visa. Nel frattempo il primo album dei Vinegar Joe era uscito. Elkie e Pete Gage mi contattarono. Stavano pianificando di rimpiazzare il loro tastierista ed il batterista e mi chiesero di unirmi con loro al basso. Avevamo sempre ammirato il sound alla batteria di Pete Gavin con gli Head, Hands & Feet. Il gruppo si stava sciogliendo così Pete fu d’accordo. Incidemmo il secondo album “Rock & Roll Gypsies” con Keef Hartley alla batteria. Anche il chitarrista Jim Mullen aderì in quel periodo. Il nuovo tastierista fu Mike Deacon. Jim ci lasciò dopo il nostro tour negli States nel 1973. Incidemmo “Six Star General” con Elkie, Robert Palmer, Pete Gage, il sottoscritto e Pete Gavin. Dei tre album è il mio preferito. Uscì e la prima stampa si esaurì in fretta, ma la crisi del vinile colpì duro perciò ci fu un grande ritardo prima della ristampa successiva. In seguito Robert annunciò di lasciarci per intraprendere una carriera solista. Venne fuori che Chris Blackwell e Robert avevano semplicemente usato la band per privilegiare Robert. Eravamo intenzionati ad andare avanti senza di lui e registrammo due pezzi con Elkie. La Island fece uscire poche copie in Olanda ma ritirò il disco nel momento in cui decise di non supportare più la band senza Robert. A quel punto ci sciogliemmo. Qui ci sono delle clip di tracce “perse”: “Sweet Nothings” (l’unica volta in cui ho suonato il basso con un plettro!) e “Rescue Me”. |

|

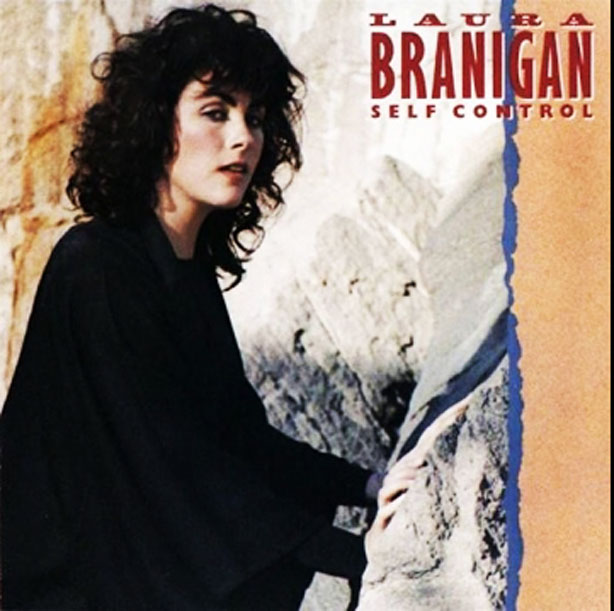

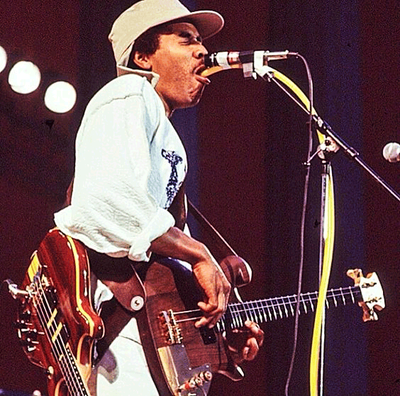

Following the break up of Vinegar Joe in 1974 I found myself in demand for session work. This lasted until 1981 when studio work dropped off drastically in both the US and the UK. I saw the writing on the wall and, after recording the follow up album to Marianne Faithfull’s “Broken English”, I moved to New York. Studio work was declining there too and I was lucky enough to tour with Laura Branigan until 1985, during the period when she was having hit records. In 1985 I moved to Minneapolis because I knew there was a good live music scene there and I had some work offers there. My experience enabled me to expand from just playing bass to also working as musical director for artists touring without their own musicians. These were mainly blues and oldies acts such as Chuck Berry, Bo Diddley, The Coasters, The Platters, The Drifters, the Inkspots, Fabian, The Shirelles, Syl Johnson and many more. I also somehow ran a booking agency from 1988 until I moved to Mexico in 2005. |

Successivamente alla rottura dei Vinegar Joe nel 1974 mi ritrovai a fare domanda in giro come turnista. Questa situazione durò fino al 1981 quando il lavoro in studio scomparve drasticamente sia negli Stati Uniti che nel Regno Unito. Capii l’antifona perciò dopo aver registrato l’album successivo a “Broken English” di Marianne Faithfull (Dangerous Acquaintances, ndr), mi trasferii a New York. Il lavoro in studio era in declino anche lì e fui abbastanza fortunato da andare in tour con Laura Branigan fino al 1985, durante il periodo in cui lei stava collezionando dischi di successo. Nel 1985 mi trasferii a Minneapolis perché sapevo che c’era una buona scena di musica dal vivo tanto che ricevei delle offerte di lavoro lì. La mia esperienza mi rese capace di maturare non solo come bassista ma anche in qualità di direttore musicale per gli artisti che andavano in tour senza i loro musicisti. Si trattava principalmente di performance blues e di vecchi successi come Chuck Berry, Bo Diddley, The Coasters, The Platters, The Drifters, the Inkspots, Fabian, The Shirelles, Syl Johnson e molti altri. In qualche modo gestii anche un’agenzia di prevendite dal 1988 fino a quando non mi sono trasferito in Messico nel 2005. |

|

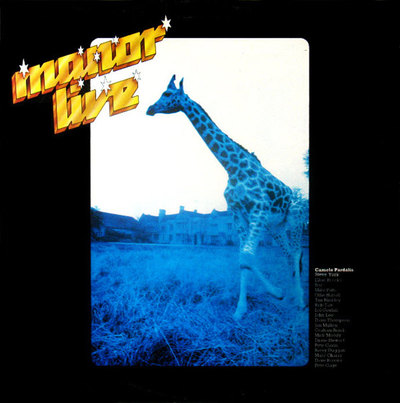

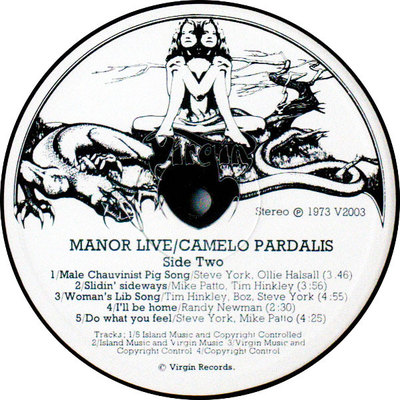

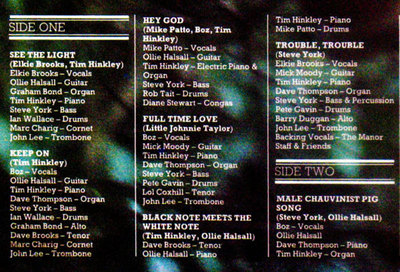

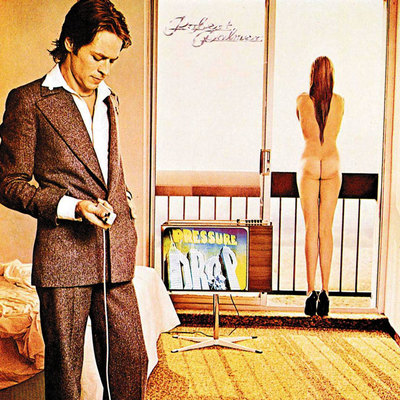

BMF: Would you like to tell us about the project Camelo Pardalis, and the record Manor Live, that is included in all the official discographies as your solo album? SY: The story is here! A Pregnant Giraffe, a Bassist on Crutches… What Else but the Manor, Live! BMF: Among your many collaborations, some names stand out like Marianne Faithfull, Robert Palmer, Dr. John, Graham Bond, Manfred Mann, Arthur Brown, Joan Armatrading. These are central figures of rock scene and not just of it. Which were the collaborations that gave you more satisfaction? Can you report any stories about any of those experiences? I’ll add a couple more that stand out for me. Marianne Faithfull. “Broken English” was a ground breaking record at the time. Steve Winwood had a lot to do with shaping that album. It is interesting that Island released the double CD with the original mixes without Steve Winwood along with the final version. Marianne and I agreed that we prefer the rougher original version but it would not have been as successful in that form. Marianne wrote the lyrics for some the original songs and the core four piece band collaborated on the music.This album has gone gold and platinum in many countries over the years . I have often walked into sessions and been told «We need you to come up with a bass part to make this song a hit!». Sometimes someone does the right thing and gives the bassist (or drummer) a writing credit for this! This was one of them! Marianne is a fine actress and I think this really shows in her performance. |

BMF: Vorresti raccontare ai nostri lettori del progetto Camelo Pardalis, “Manor Live”, che le discografie ufficiali ti attribuiscono come lavoro solista? SY: Ecco a voi la storia! Una giraffa incinta, un bassista sulle stampelle.. Che altro oltre a Manor, live! BMF: Nella lunga lista di tue prestigiose collaborazioni, spiccano anche nomi come Marianne Faithfull, Robert Palmer, Dr. John, Graham Bond, Manfred Mann, Arthur Brown, Joan Armatrading. Davvero personaggi centrali della scena rock e non solo. Quale è stata la collaborazione che ti ha regalato più soddisfazioni? Puoi raccontarci degli aneddoti al riguardo? SY: Ne aggiungerò un paio di più che risaltano secondo me. Marianne Faithfull. “Broken English” era un disco rivoluzionario a quel tempo. Steve Winwood ebbe un gran da fare nel dar forma a quell’album. È interessante il fatto che la Island fece uscire il doppio CD con il mix originale senza di lui nella versione finale. Marianne ed io preferivamo entrambi la versione iniziale più ruvida ma non avrebbe avuto lo stesso successo. Marianne scrisse i testi per alcune delle canzoni originali e il nucleo di quattro elementi della band collaborò alla musica. Quest’album ha ottenuto dischi di platino e d’oro in molti paesi negli anni. Spesso entravo durante le sessioni e mi veniva detto «Abbiamo bisogno di te per elaborare una parte di basso e rendere questa canzone una hit!». Alcune volte succede che qualcuno faccia la cosa giusta e dia fiducia al bassista o al batterista nella scrittura per questo! Questa fu una di quelle volte! Marianne è un’attrice raffinata e credo che ciò traspaia nelle sue performance. |

|

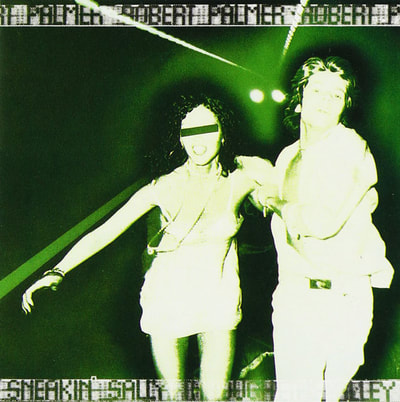

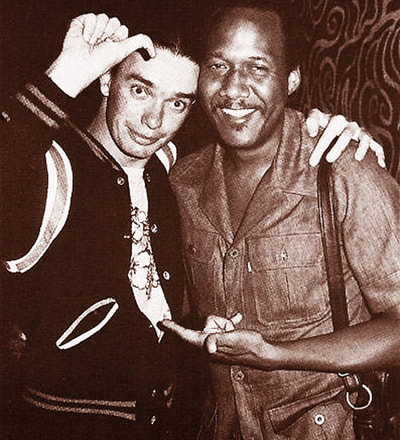

Robert Palmer. I did not have much involvement with Robert after Vinegar Joe, I mostly played harmonica on his first two solo albums. We did keep in touch over the years until a few months before his death. I do have one story about Robert that bass players might appreciate. At one rehearsal he asked me to use a foam mute under my strings for no reason other tha he had just found out that James Jamerson used one. I replied, «Sure Robert, I’ll put some foam under my strings if you’ll put a piece of foam in your mouth when you sing!». Dr John & Graham Bond. I learned a tremendous amount from both of them. Graham had a tremendous intensity when he played. When I first worked with him he told me, «I always tell my players to bring a spare shirt! You’ll sweat playing with me!». I recorded with Dr John in 1970 after Graham and American tuba player Ray Draper recommended me. I lived in New York in the early 80’s and worked a little with Dr John there. He lived close by and I spent a lot of time at his home jamming with him and listening to music. This was the period when he stopped using drugs and got his career back on track. Graham and Dr John were good friends. When Dr John arrived in London there was a drought. He had the reputation of being connected with voodoo and that it always rained when he performed. Sure enough it started raining heavily during our first session at London’s Trident studio. A few months later I went to Trident to record with Graham. Graham decided that he would also make it rain as both he and Dr John were Scorpios ( a water sign). He started an incantation with his eyes shut holding a chalice in front of him. Musician Victor Brox thought that Graham was offering him a drink and took a drink from the cup which contained perfume! He flailed his arms and knocked over a candle which set fire to the studio wall! So Graham actually managed to conjure up fire instead of water. The Dr John album was “The Sun, The Moon & Herbs”. It was originally intended to be a triple album. One of those was acoustic with Dr John on piano, Eric Clapton on 12 string guitar, me on my old acoustic bass guitar, and various drums, percussion, horns and back up vocalists. The three albums were combined into one which is a bit of a mess! Mac (Dr John) told me that the original tapes were lost. |

Robert Palmer. Non ho avuto molti rapporti con Robert dopo i Vinegar Joe. Ho per lo più suonato l’armonica nei suoi primi due album solisti. Ci tenemmo in contatto negli anni fino a pochi mesi prima della sua morte. Ho un’aneddoto riguardo a Robert che i bassisti dovrebbero apprezzare. Durante una prova mi chiese di usare il foam muting sulle mie corde per nessuna ragione in particolare se non che venne a sapere che James Jamerson ne usava uno. Così gli replicai «Certo Robert, metterò un po’ di gomma piuma sotto le mie corde se te ne ficchi una in bocca quando canti!». Dr John & Graham Bond. Ho appreso molte cose da entrambi. Graham aveva un’intensità tremenda quando suonava. Quando collaborai per la prima volta con lui, mi fece: «Dico sempre ai miei musicisti di portare una maglietta di riserva! Si suda suonando con me!». Registrai con Dr John nel 1970 dopo che il suonatore di tuba dei Graham And American mi raccomandò. Vivevo a New York agli inizi degli anni ’80 e collaborai un po’ con Dr John lì. Lui abitava nei paraggi così trascorrevo molto tempo a casa sua improvvisando e ascoltando musica. Quello era il periodo in cui smise di fare uso di droghe e si era rimesso in pista. Graham e Dr John sono stati dei buoni amici.Quando Dr John venne a Londra ci fu un peggioramento. Si era guadagnato la fama di essere connesso con il voodoo e che piovesse sempre quando si esibiva. Certo fu, che iniziò a piovere abbondantemente durante la nostra prima seduta di registrazione al Trident Studio di Londra. Pochi mesi più tardi andai al Trident per incidere con Graham. Lui decise che avrebbe fatto venire a piovere di nuovo dal momento che sia io che Dr John eravamo dello scorpione (un segno d’acqua). Iniziò un incantesimo con gli occhi chiusi impugnando un calice. Il musicista Victor Brox pensò che Graham gli stesse offrendo da bere e fece un sorso dalla coppa che conteneva profumo! Dimenò le braccia e fece cadere una candela che diede fuoco alla parete dello studio! Perciò Graham in realtà riuscì ad evocare il fuoco al posto dell’acqua. L’album di Dr John si intitola “The Sun, The Moon & Herbs”. In origine doveva essere un triplo disco, ciascuno acustico con Dr John al piano, Eric Clapton su una chitarra a 12 corde, il sottoscritto sul mio datato basso acustico, e svariate percussioni, batterie, fiati e cori. I tre album furono riuniti in uno, il che è un po’ un pasticcio! Mac (Dr John) mi disse che le registrazioni originali andarono perse. |

|

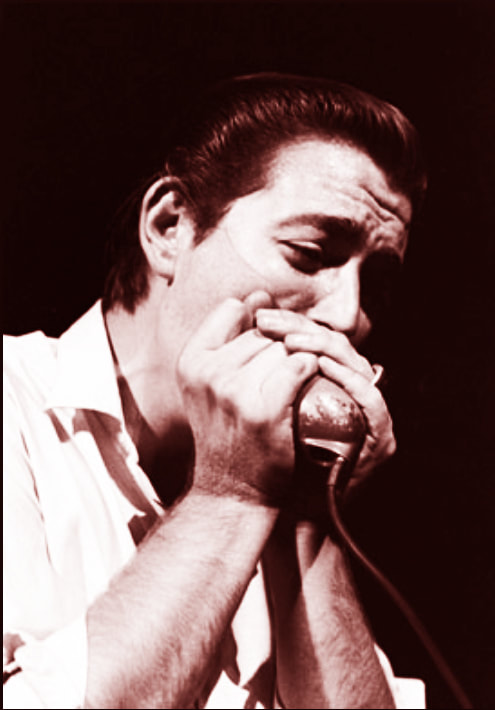

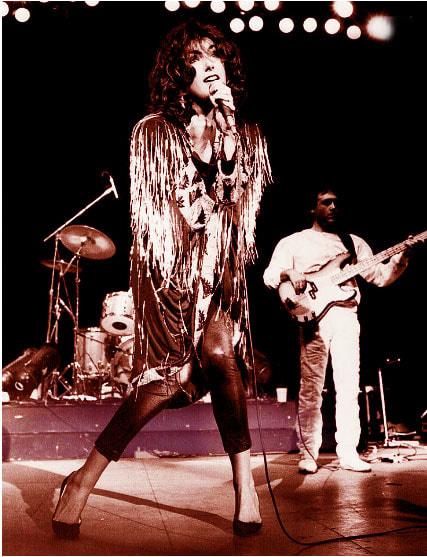

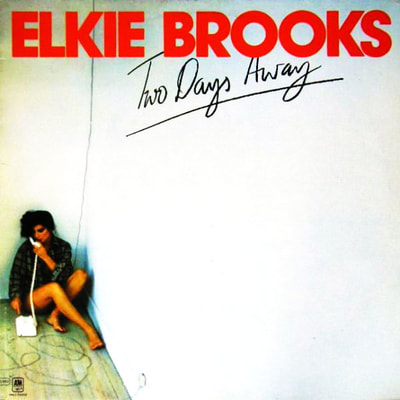

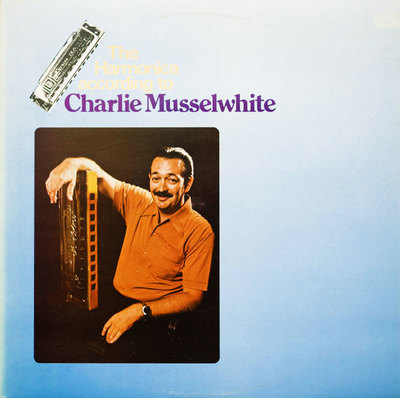

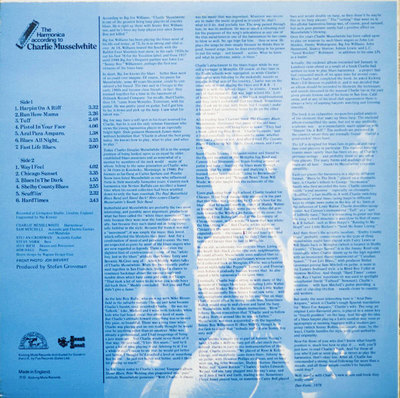

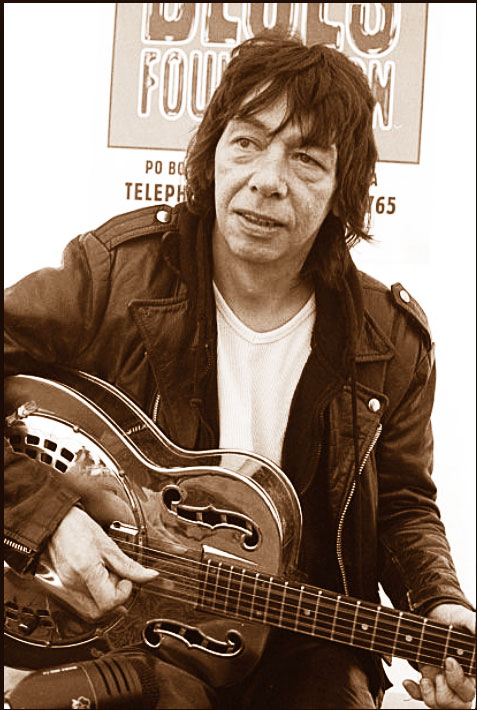

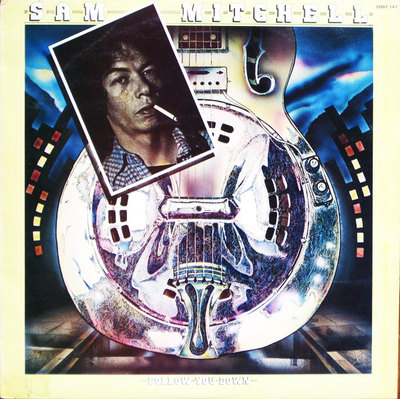

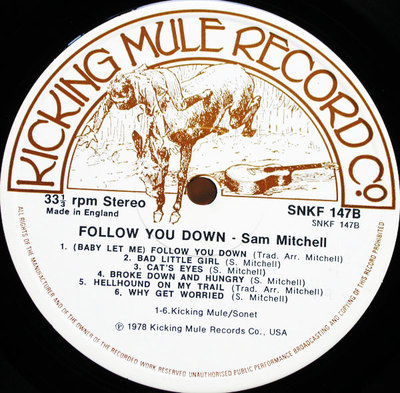

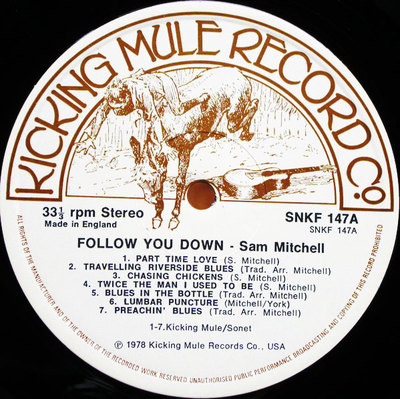

Elkie Brooks. One of my favourite albums on which I played is Elkie’s “Two Days Away” which sadly is hard to find. It was a great experience working with producers Jerry Leiber & Mike Stoller. They worked very methodically, laying the rhythm tracks we would generally work from 10am -6pm and record four batches of about ten takes at a time. After each batch we would take a break and then they would tell us what to change or what to keep. I couldn’t understand why they did so many takes until we were done with the rhythm tracks and Elkie asked when she was going to do the vocals. They said “We’ve already got them!” They were keeping the guide vocals looking for natural performances.The album contained two of Elkie’s biggest hits “Pearl’s A Singer” and “Sunshine After the Rain”. I also later played on another of her hits “Lilac Wine” which was recorded live in the studio in one take with a full orchestra. Charlie Musselwhite. I enjoyed recording Charlie’s “The Harmonica According To ….” Album produced by Stefan Grossman. The great slide guitarist Sam Mitchell was on the session. We had three days booked and we completed Charlie’s album in a day and a half so we recorded some tracks for Sam’s album. Jeff Rich was the drummer. Charlie is one of the best blues harmonica players ever! |

Elkie Brooks. Uno dei miei album preferiti su cui ho suonato è “Two Days Away” che purtroppo è difficile da reperire. È stata un’esperienza grandiosa lavorare con i produttori Jerry Leiber & Mike Stoller. Hanno operato molto metodicamente, dando il ritmo alle tracce, in genere lavoravamo dalle dieci del mattino alle sei del pomeriggio e registravamo in quattro serie di circa dieci riprese per volta. Alla fine di ciscuna serie ci prendevamo una pausa e dopo ci dicevano cosa bisognava cambiare e cosa mantenere. Non riuscivo a capire perché facessero così tante incisioni fino a quando non avessimo chiuso con le sessioni ritmiche. Poi Elkie chiese quando avrebbe potuto lavorare alle parti vocali. Loro risposero «Le abbiamo già!». Non fecero altro che conservare la voce principale ricercando le performance naturali. L’album conteneva due delle più belle hit di Elkie “Pearl’s A Singer” e “Sunshine After the Rain”. In seguito ho anche suonato su altre sue hit “Lilac Wine” che fu registrata dal vivo in studio in un’unica ripresa con l’orchestra al completo. Charlie Musselwhite. Mi sono divertito a registrare l’album di Charlie “The Harmonica According To ….” Prodotto da Stefan Grossman. C’era il grande chitarrista slide Sam Mitchell durante la registrazione. Avevamo prenotato tre giorni e ce ne bastò uno e mezzo per completare l’album perciò registrammo alcune tracce per il dico di Sam. Jeff Rich era alla batteria. Charlie è in assoluto il miglior suonatore di armonica blues! |

|

|

|

|

|

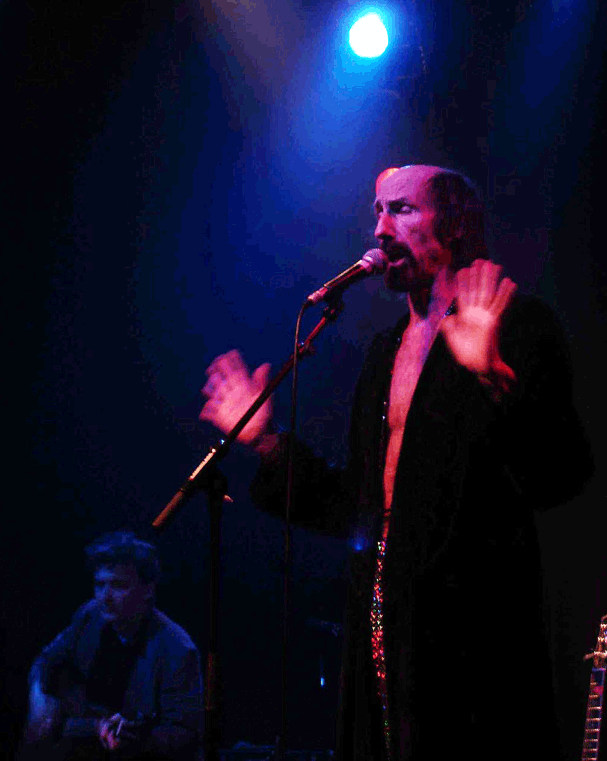

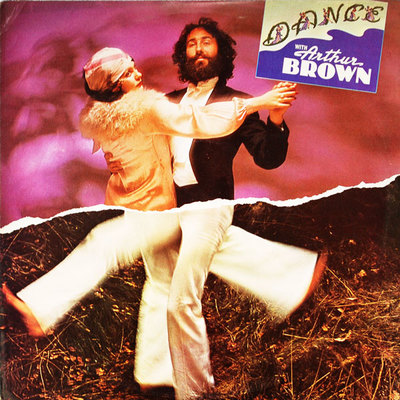

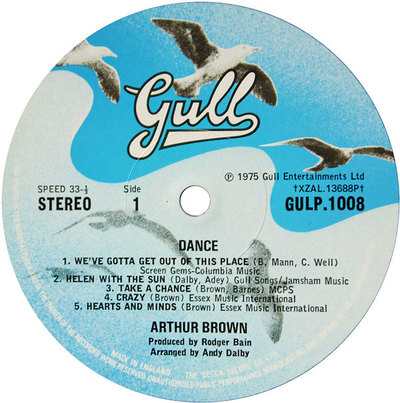

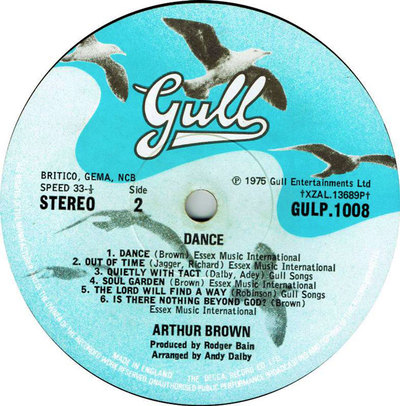

Manfred Mann. See above! I did have a surprise about four years ago when I received an email asking how I got my bass sound on the track “Stand Up” by Prodigy. It was sampled from the Manfred Mann track “One Way Glass”. I discovered that it had sold 1.2 million and I put in a claim for royalties through PPL. It was a nice little bonus in my old age! Arthur Brown. I got called in to finish Arthur’s “Dance” album after the bassist on the sessions became indisposed. I was recommended by one of my favourite drummers, Charlie Charles. I went on to work with Arthur doing live shows and TV for a few years. He was always fun to work with and had good musicians with him. |

Manfred Mann. Vedi sopra! Ebbi una sorpresa circa 5 anni fa quando ricevei un e-mail in cui mi chiedevano come fossi riuscito ad ottenere quel sound al basso sulla traccia “Stand Up” dei Prodigy. Era stata selezionata dalla traccia dei Manfred Mann “One Way Glass”. Ho scoperto che aveva venduto 1,2 milioni perciò feci domanda per le royalties attraverso il PPL. È stato un bel bonus alla mia vecchia età! Arthur Brown. Fui chiamato per finire l’album “Dance” di Arthur, dopo che il bassista ingaggiato per la registrazione si indispose. Fui segnalato da uno dei miei batteristi preferiti, Charlie Charles. Continuai a collaborare con Arthur facendo spettacoli e show televisivi per alcuni anni. Era divertente e aveva grandi musicisti al proprio fianco. |

|

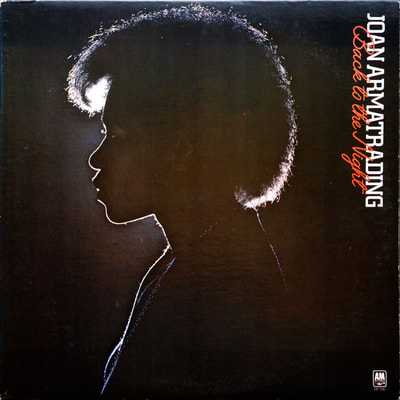

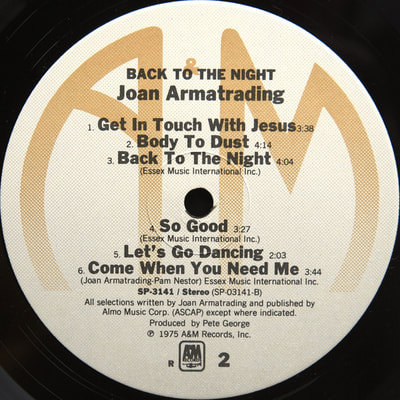

Joan Armatrading. I played on her “Back To The Night” album. She is a unique songwriter. It was not easy to figure out her material as she was not communicative. She used open tunings so the bottom three strings of her guitar were usually a D, A, D drone so I had to figure out where the bass should move. Also she played a lot of 9/8 and 7/8 bars so we had to keep having her repeat sections to figure out if she was dropping or adding beats consistently or not ( she was). Eventually I got to know her a little better and she was a very nice person. I love her album “Into The Blues”! Laura Branigan. After I moved to New York in 1981 I was fortunate to tour with Laura during her hit record period from 1982 – 1985. This was fine band with my old friend Virgil Weber as musical director. I never recorded with her but they did release a live video of a concert in Lake Tahoe. |

Joan Armatrading. Ho suonato sul suo album “Back To The Night”. Si tratta di una cantautrice unica. Non fu così semplice comprendere il suo materiale dal momento che lei non era così loquace. Usava melodie aperte così le tre corde di base della sua chitarra erano solitamente RE, LA, RE ripetuti perciò dovevo dedurre a che punto il basso sarebbe dovuto partire. Inoltre lei suonava molte battute in 9/8 e in 7/8 così dovevamo continuare a portare avanti le sue parti ripetute per intuire se stava saltando o aggiungendo battute regolarmente o meno. Alla fine riuscii a conoscerla meglio ed era davvero una bella persona. Adoro il suo album “Into The Blues”! Laura Branigan. Dopo essermi trasferito a New York nel 1981 fui fortunato ad andare in tour con Laura durante la fase del suo disco di successo dal 1982 al 1985. Si trattava di una band molto forte con il mio vecchio amico Virgil Weber come direttore artistico. Non ho mai inciso con lei ma fecero uscire un video dal vivo di un concerto a Lake Tahoe. |

|

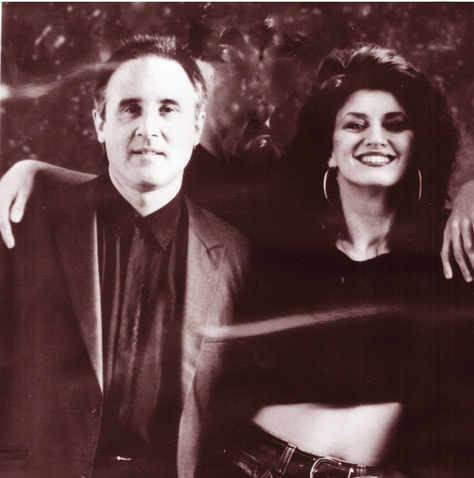

BMF: You have been living in Puerto Vallarta, Mexico. Is this life choice also based on professional commitments? SY: No. It’s based on a lack of professional commitments! I play live regularly here and teach privately. I occasionally collaborate in recordings via the internet. I consider myself semi retired. I enjoy playing locally here. I have particularly enjoyed playing with Tex Mex singer/guitarist Joe King Carrasco, The Banderas Bay Jazz Allstars, and currently playing reggae jazz with The Jamaican Brothers. I also enjoy working with my wife , vocalist and pianist Lisa York. We play together locally a couple of times a month and have also worked together as a duo on cruise ships over the past few years. Music is an important part of Mexican culture. The people here have a deep appreciation of music and musicians. Respect for the aged is also part of the culture. At nearly 70 years old I was thrilled when a girl in her 20’s recently said to me after a concert, «When you play you look like music». |

BMF: Da molti anni vivi in Messico, a Puerto Vallarta. Questa tua scelta di vita è stata motivata (anche) da impegni professionali? SY: No. È da ricondurre ad una carenza di ingaggi professionali! Mi esibisco regolarmente qui e insegno privatamente. Collaboro occasionalmente in registrazioni via internet. Mi considero un semi-pensionato. Mi piace suonare in loco qui. Mi sono divertito in particolare a suonare con il chitarrista e cantante dei Tex Mex, Joe King Carrasco, con i Banderas Bay Jazz Allstars e attualmente suono reggae jazz con i Jamaican Brothers. Mi piace molto anche lavorare con mia moglie, la cantante e pianista Lisa York. Ci esibiamo qui insieme un paio di volte al mese ed abbiamo persino lavorato come duo sulle navi da crociera negli anni passati. La musica è un aspetto importante della cultura messicana. Le persone qui hanno un’alta considerazione della musica e dei musicisti. Il rispetto per le persone anziane ne è un'altra componente. All’età di quasi 70 anni sono rimasto elettrizzato quando una ragazza di 20 anni ultimamente mi ha detto dopo un concerto: «Quando suoni incarni la musica»! |

|

|

|

|

BMF: You belong to a worthy generation of solid, imaginative and remarkable English bassists . Your style on bass reflects and enhances all of its features, intended as an elegant and refined as well as powerful and creative accompanying instrument . So I want to know your opinion about the level of the emancipation of bass… Did the Copernican Revolution led by Jaco finish its impulse or is there anything new, slowly coming into place? SY: Thanks for the kind words! There are a few factors that have changed everything since Jaco. The quality of equipment has evolved tremendously.The opportunities for bassists to play live with other musicians on stage or in the studio on a professional level have declined drastically. The internet now has made vast amount of information available. With the technology advances, musicians can record and post their work on the internet without leaving home. Electric bass is no longer mainly an American instrument. It has become international. Historically bass was an accompanying instrument. In the seventies Jaco, Stanley Clarke and several others expanded it to a fully collaborative instrument. Now we are seeing more solo bassists than ever before. There is less opportunity for bassists to play with others live or in the recording studio. I am seeing two types of videos from current bassists. There are those who treat the bass primarily as a solo instrument, usually playing in the upper registers and using a wide variety of techniques. I prefer to think of this as “baritone guitar” . I do not mean this to be derogatory. Many of them are amazing and I admire and enjoy their work, but I do not think of it as “bass playing”. It is great to see so many expanding the range of possibilities on the instrument but so many seem to be making music solely for other bassists. Jaco’s style and the styles of the slap pioneers have influenced main stream music. How many of the cutting edge bass styles of today become part of everyday bass vocabulary remains to be seen. Meanwhile I admire many of these players for their compulsion to innovate . Then there are those who post videos of themselves playing conventional rhythm section bass along with tracks or drum machines. Many of these do an excellent job of copying every inflection from a record. But I am puzzled as to why they do this! In the past 20+ years I have been hired as musical director as well as bassist. If these videos are intended as audition “calling cards” they do not tell me how quickly the musician can comprehend and execute a piece of music, or how they adjust to and collaborate with other musicians. If they are intended as an aid to others to learn a specific song they have some value but in the long term they are really detracting bassists from really becoming complete musicians. To me ensemble music at it’s best is a conversation between musicians and to participate the bassist needs to learn the language, vocabulary and grammar of whatever style of music is being played and then to have some ideas to bring to the conversation and also to be capable of supporting and playing around the ideas of others. I find it very sad that there are so many young,talented and dedicated bassists sitting at home playing with machines instead of with other musicians. Even collaborations on the web do not compare to musicians being in the same space sharing energy and inspiration with each other and a live audience! |

BMF: Appartieni a una nobile generazione di bassisti inglesi solidi, fantasiosi e di spessore. Il tuo modo di suonare è prettamente bassistico, inteso come accompagnamento elegante e raffinato, ma anche potente e fantasioso. Allora ti chiedo: a che stato è, secondo te, il basso elettrico oggi? La rivoluzione “copernicana” portata da Jaco ha esaurito la sua spinta o c’è qualcosa di nuovo che sta vedendo la luce? SY: Grazie per le belle parole! Ci sono alcune cose che hanno rivoluzionato ogni cosa dopo Jaco. La qualità della strumentazione si è evoluta enormemente. Le opportunità per i bassisti di esibirsi dal vivo con altri musicisti sul palco o in studio ad un livello professionale sono diminuite drasticamente. Internet ora ha reso disponibili un mucchio di informazioni. Grazie all’innovazione tecnologica, i musicisti sono in grado di registrare e pubblicare i loro lavori on line senza uscire di casa. Il basso elettrico non è più uno strumento primariamente americano. È diventato internazionale. Dal punto di vista storico il basso è sempre stato uno strumento di accompagnamento. Negli anni ‘70 Jaco, Stanley Clarke e diversi altri lo promossero a strumento pienamente collaborativo. Ora vediamo più bassisti solisti che mai. C’è meno possibilità per loro di suonare con gli altri dal vivo o negli studi di registrazione. Di solito vedo due tipologie di video postati dai bassisti attuali. Ci sono quelli che trattano il basso principalmente come strumento solista, di solito suonando nel registro alto e servendosi di un’ampia gamma di tecniche. Preferisco considerarlo una chitarra baritona. Non lo intendo in senso dispregiativo. Molti di loro sono bravi e ammiro e mi piace il loro lavoro ma non credo che suonino il basso. È grandioso vedere così tanti di loro ampliare il ventaglio delle possibilità dello strumento ma molti sembrano fare musica esclusivamente per altri bassisti. Lo stile di Jaco e lo stile di slap dei pionieri del genere hanno influenzato molto il main stream. Resta da vedere quanti degli stili di massima espressione del basso di oggi diventeranno parte del vocabolario quotidiano dello strumento. Nel frattempo non mi resta che apprezzare molti di questi musicisti per la loro spinta ad innovare. Poi ci sono quelli che postano video di loro stessi che suonano sezioni ritmiche di basso convenzionali su tracce o batterie elettroniche. Molti di loro fanno un ottimo lavoro di imitazione di ogni intonazione del disco. Eppure rimango piuttosto perplesso sul perché lo fanno! Più di vent’anni fa fui ingaggiato come direttore artistico oltre che come bassista. Se questi video sono da intendersi come provini di presentazione, non mi dicono quanto velocemente il musicista riesca a comprendere ed eseguire un pezzo, o a quanto riescano ad adattarsi o a collaborare con altri musicisti. Se sono concepiti per aiutare gli altri ad imparare una canzone in particolare, allora hanno un qualche valore ma a lungo termine distolgono i bassisti dal diventare dei musicisti completi. Per me la musica d’insieme è - nella migliore delle ipotesi - una conversazione tra musicisti e per partecipare il bassista ha bisogno di apprendere il linguaggio, il vocabolario e la grammatica di qualsiasi stile di musica lui si trovi a suonare ed in un secondo tempo di elaborare alcune idee con cui arricchire lo scambio di battute ed essere in grado di supportare e ricamare sulle idee degli altri. Trovo molto triste che ci siano così tanti bassisti giovani, di talento e zelanti seduti a casa a suonare con i computer piuttosto che farlo con i musicisti. Anche le collaborazioni sul web non hanno niente a che vedere con il trovarsi nello stesso posto condividendo l’uno con l’altro l’energia e l’ispirazione oltre al pubblico dal vivo! |

|

In the big picture many bassists are also fine composers and musical directors. There is a long list of such players. In recent years Michael League, Richard Bona and Esperanza Spaulding spring to mind. ( Of course the latter two are also vocalists.) The fundamentals of music do not change but the technology and the means of distribution have had a huge effect on bassists and music in general. Electric bass was originally developed in the USA and when I started it was really difficult to find a good instrument outside the US or to get to hear a lot of the music from USA. Now it has spread all over the world. It is no longer just an instrument for American music. In the end there will always be individual musicians expanding the boundaries of the instrument and creating great music. |

Nel quadro d’insieme molti bassisti sono anche eccellenti compositori e direttori musicali. C’è una lunga lista di artisti simili. Negli ultimi anni mi vengono in mente Michael League, Richard Bona ed Esperanza Spaulding (certamente gli ultimi due sono anche cantanti). I fondamenti della musica non cambiano eccezion fatta per la tecnologia ed i canali di distribuzione che hanno avuto un impatto enorme sui bassisti e la musica in generale. Il basso elettrico è stato in origine sviluppato negli Stati Uniti e quando iniziai a suonarlo fu molto difficile trovare un buono strumento al di fuori degli States o andare a sentire molta musica proveniente dagli States. Ora si è diffuso in tutto il mondo. Non è più solo uno strumento esclusivo della musica americana. In ultima analisi ci saranno sempre musicisti che singolarmente forzeranno i limiti dello strumento, realizzando musica straordinaria. |

|

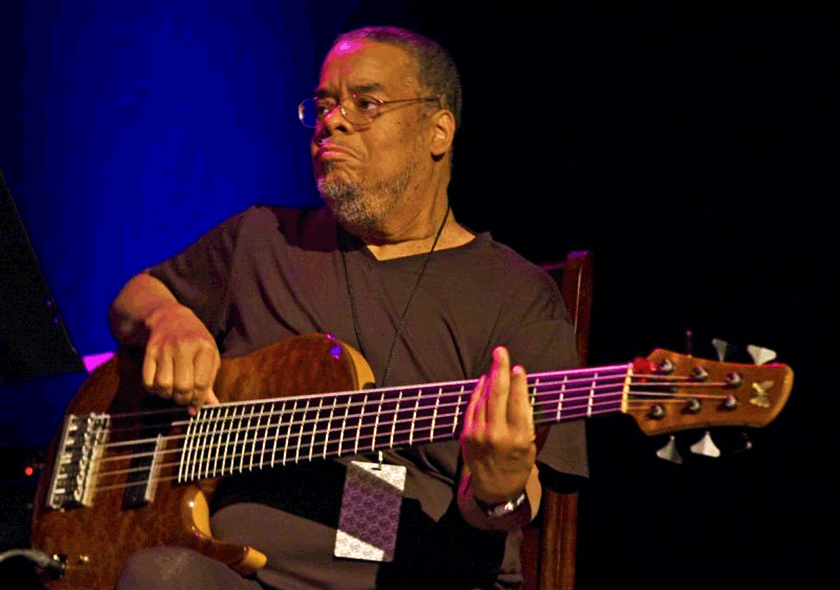

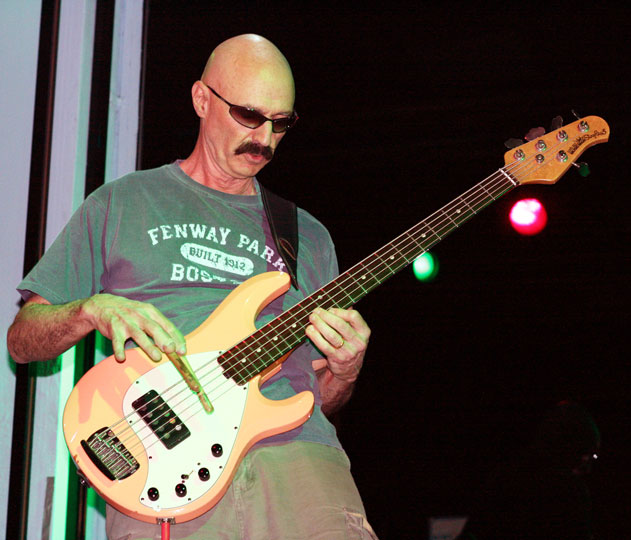

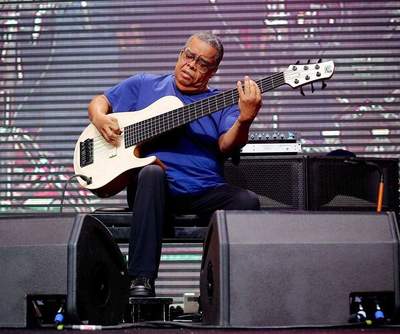

BMF: And in this respect, who are the contemporary bassists whom you like most and whom you gladly listen to? SY: Most of the “contemporary” bassists I listen to are around my age or older and doing some of their best work! Anthony Jackson is the first that comes to mind, especially for his work with Michel Camilo and also for his thoughtful articles. John Patitucci for his mastery of both upright and electric. Abraham Laboriel is constantly inventive. Nashville seems to be one of the last locations where studio bassists are valued and I always enjoy listening to players such as Willie Weeks, Michael Rhodes, Emory Gordy Jr and Dave Pomeroy. Following my comment about how electric bass has spread from the USA into music all over the world, I try listen to music of many genres but it is difficult to cover everything! Living in Mexico I hear some phenomenal contemporary bassists in all forms of Latin music, especially Latin jazz. To mention a couple of my favourite bassists / educators I always enjoy the work of Joe Hubbard and Oscar Stagnaro. I see many outstanding bassists on youtube and facebook but Federico Malaman always stand out, especially for his humour and exuberance! |

BMF: E a questo proposito, quali bassisti contemporanei sono di tuo gradimento e quali ascolti volentieri? La maggioranza dei bassisti odierni che ascolto hanno più o meno tutti la mia età o sono più grandi e fanno del loro meglio! Anthony Jackson è il primo che mi viene in mente, specie per il suo lavoro con Michel Camilo e anche per i suoi lavori riflessivi. John Patitucci per la sua maestria sia sul basso che sul contrabbasso. Abraham Laboriel è perennemente creativo. Nashville sembra essere l’ultima location dove i bassisti di studio siano apprezzati e mi diverto sempre ad ascoltare artisti come Willie Weeks, Michael Rhodes, Emory Gordy Jr e Dave Pomeroy. Riprendendo le mie considerazioni su come il basso elettrico si sia sviluppato a partire dagli Stati Uniti nella musica di tutto il mondo, cerco di ascoltare diversi generi ma è difficile scoprirli tutti! Vivendo in Messico seguo alcuni bassisti fenomenali in tutte le forme della musica latina specialmente il Latin jazz. Per citare un paio dei miei bassisti/insegnanti preferiti mi piacciono sempre i lavori di Joe Hubbard e Oscar Stagnaro. Seguo molti bassisti notevoli su youtube e facebook ma Federico Malaman si distingue sempre specie per il suo humour e la sua esuberanza! |

|

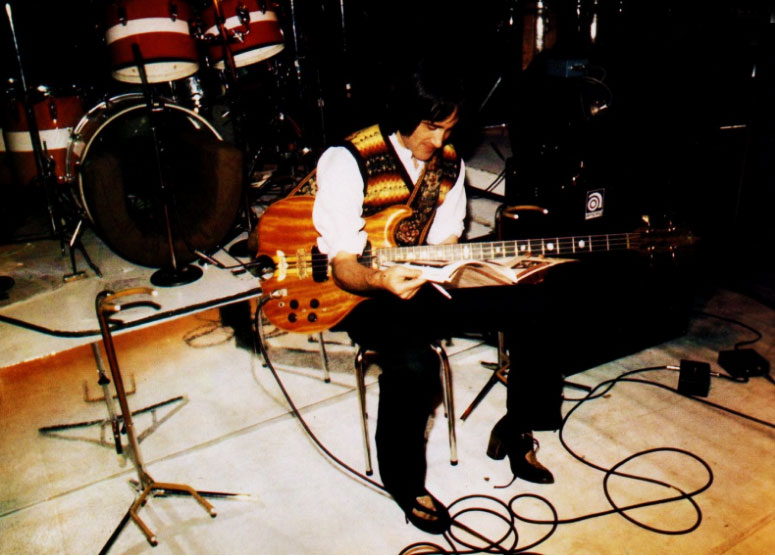

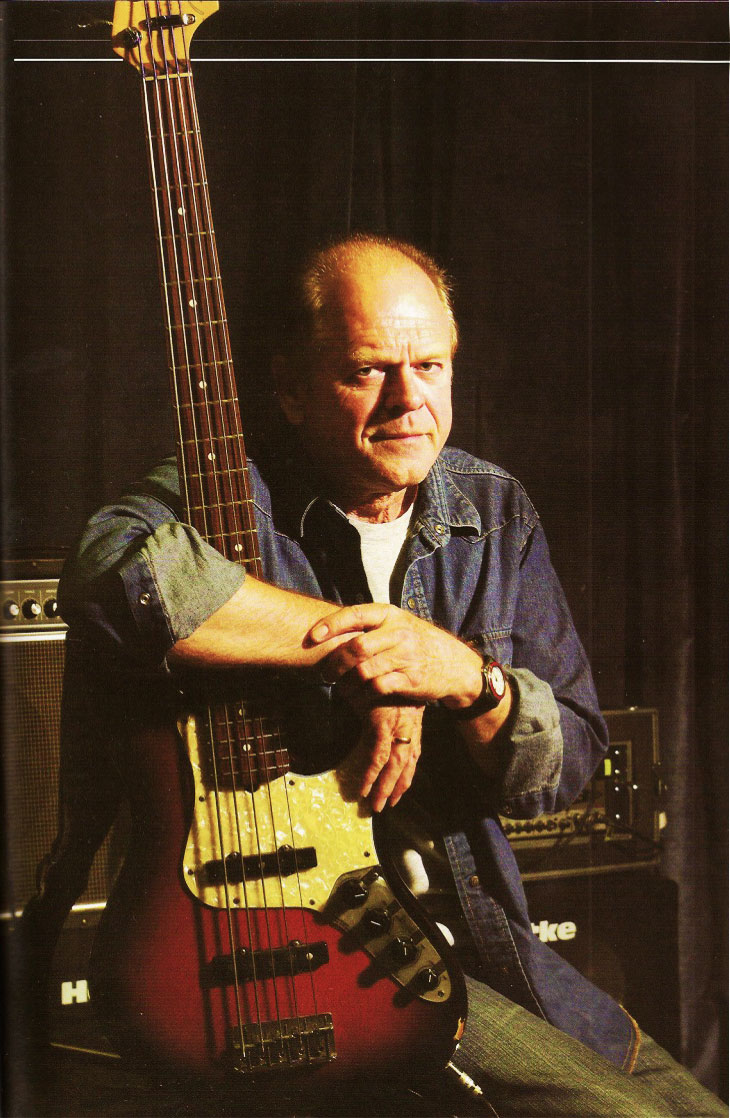

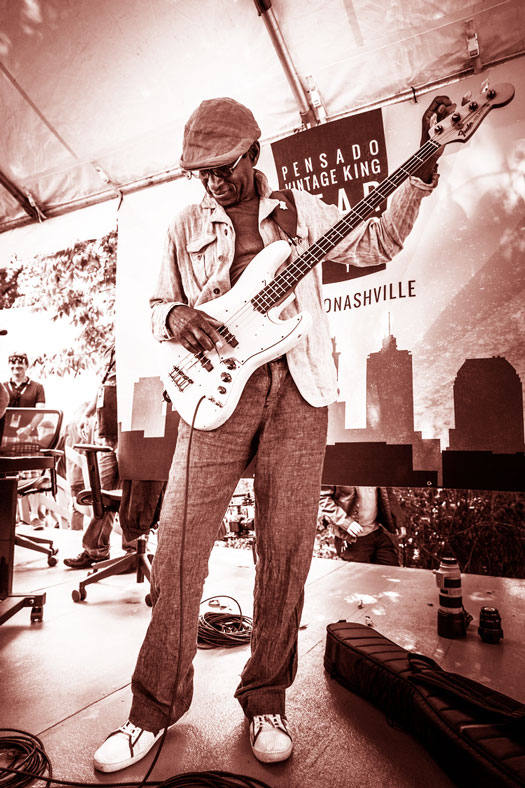

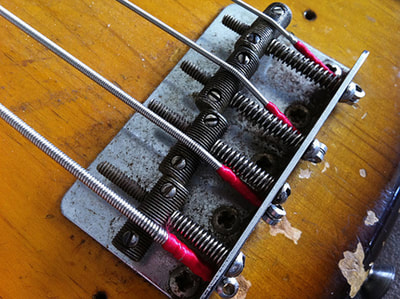

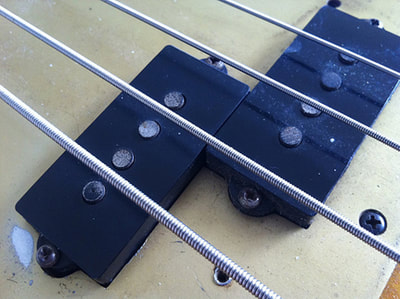

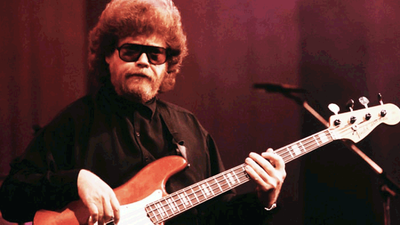

BMF: I want to ask you something about Robert Palmer who is considered as one of the most underrated singer/musician of the rock scene. What kind of person was he? Is it true that his modesty didn’t facilitate him? I supposed you knew him very well… SY: Yes, I did know Robert well. I do not see him as underrated. He was a star in the US and was a multi millionaire when he died. Also, he was anything but modest. He was likeable, but very ambitious and totally self centered as are many successful singers. BMF: We would like to know something about the history of your gear. What’s your current gear? SY: I’m currently stripping down my gear collection. My choice of equipment is governed by my circumstances. I do not collect basses . If I haven’t used a bass for five years it generally gets sold , no matter how much sentimental value it has. I endorse both Fodera and Lakland basses. I have found both companies to be great to deal with! My main bass is a 2009 Fodera Imperial Essence that I bought in 2013. I changed the hardware to chrome. When I removed the bridge I saw that the date of completion was the same as my birthday! This makes it very personal! It has an exceptionally deep sound for a Fodera. I can get all the sounds I looked for in my favourite 1964 Fender Precision or Jazz basses ( the pickups are in the 60’s jazz position.) My other Fodera is a 2004 Emperor Elite II . I recently found out that it was built as a NAMM show bass. The sound is more in the range of my old 1974 maple neck Fender Jazz bass. This one mostly stays at home for recording. The reason I play the Foderas is because they have great touch sensitivity. I often play duo gigs without drums and the bass sound is very exposed. I set them up with a medium action. On one duo gig I had a compliment from a sound engineer who said ” I listen to bass through headphones all day and this is the first time in ages that I have heard a bass guitar with no fret buzz!” I have owned several US Lakland basses but the one I kept is a 2003 Skyline 55-02 with US Bartolini electronics. I recently had a new neck fitted at the factory. I string it with flatwounds and run it passive for an “old school” sound. I may rewire it for true passive. Takamine TB10I also have a Takamine TB10 fretless acoustic for the faux upright sound. It is now my only 4 string bass.Takamine TB10 Amplifiers and Speakers. I have an old Phil Jones Briefcase , mostly for recording.My concert rig is two Bergantino 12” cabs with Genz Benz Shuttlemax 9.1 heads. |

BMF: Una domanda specifica su Robert Palmer, che molti considerano uno dei cantanti/musicisti più sottovalutati della scena rock. Che persona era, è vero che la sua modestia non lo ha favorito? Tu lo hai conosciuto molto bene! SY: Sì, conoscevo bene Robert. Non credo che sia un artista sottostimato. È stato una star negli Stati Uniti ed un multimilionario quando è scomparso. Inoltre, era tutt’altro che modesto. Era piacevole ma molto ambizioso e molto autoreferenziale alla stregua di molti cantanti di successo. BMF: Ci piacerebbe conoscere nel dettaglio un po’ la storia della tua strumentazione. Quale è quella attuale e quali sono stati in passato i tuoi bassi preferiti? SY: Attualmente sto smontando la mia strumentazione da collezione. La mia scelta è dettata dalle circostanze. Non colleziono bassi. Se non uso un basso da cinque anni generalmente lo vendo, non importa il valore sentimentale che hanno. Sono endorser sia dei bassi Fodera che Lakland. Credo che sia grandioso collaborare con entrambe le aziende! Il mio basso principale è un Fodera Imperial Essence del 2009 che ho acquistato nel 2013. Ho cambiato la scheda madre facendola cromata. Quando ho rimosso il bridge mi sono reso conto che la data dell’ultimazione era la stessa del mio compleanno! Questa cosa lo rende molto personale! Ha un suono eccezionalmente profondo per un basso Fodera. Riesco ad ottenere tutti i suoni che voglio sul mio Fender Precision preferito del 1964 o sui Jazz Fender. Il mio secondo Fodera è un Emperor Elite del 2004. Recentemente ho scoperto che è stato costruito come un basso del NAMM show. Il range sonoro è più simile a quello del mio vecchio maple neck Fender Jazz del 1974. Strumento che sta per lo più a casa per registrare. La ragione per cui suono i bassi Fodera è che sono molto sensibili al tocco. Spesso mi trovo a suonare in duo senza la batteria e il sound del basso è molto in evidenza. Li metto a posto, arrangiandoli in una via di mezzo. Su una delle esibizioni in duo ho avuto i complimenti di un ingegnere del suono che mi ha detto «Ho ascoltato il basso attraverso le cuffie tutto il giorno, e questa è la prima volta da anni che ho sentito un basso senza il ronzio dei tasti!». Ho posseduto diversi Lakland statunitensi ma quello che posseggo ancora è uno Skyline 55-02 del 2003 con componenti elettroniche della Us Bartolini. Ultimamente ho montato un nuovo manico allo stabilimento. Lo accordo con corde flatwounds e lo rendo passivo per ottenere un sound di vecchia scuola. Dovrei rifarlo per renderlo un vero basso passivo. Ho anche un Takamine TB10 fretless acustico per un finto effetto contrabbasso. Ormai è l’unico basso a quattro corde che posseggo. Amplificatori e speakers. Ho un vecchio Phil Jones Briefcase, per lo più per registrare. La mia attrezzatura da concerto è costituita da due amplificatori Brigantino 12” con heads Genz Benz Shuttlemax 9.1. |

|

The amps I have used most during the last two years are Fender Rumble 500’s and 100’s, even on concert stages. For big stages I chain two 500’s. So here I am playing expensive basses through cheap amps! But at my age portability and convenience are paramount and I get compliments on the sound. I Here is a list of some of my favourite past basses. I bought my first Fender in 1968. It was a used 1964. That bass was on the East of Eden album and the first Manfred Mann Chapter 3 album. I used flatwound strings on the East of Eden album. When Rotosound swing Bass roundwounds came out I switched but they were too light for me so I used a D for a G, an A for the D, an E for the A and for the E string I would buy a LaBella nylon tapewound and scrape the tape off! Bass amps in the UK were terrible back then! I was using two 18” cans with a 100 watt Selmer amp. To cut through with Manfred I often used metal fingerpicks on the balls of my fingers. The Rotosound strings wore the frets so I traded the bass for a 64 Jazz bass and traded the neck for a P bass neck. This is the bass on the second Manfred Mann album. When we were about to record the first Vinegar Joe album I wanted a different sound and bought a 60’s Ampeg scroll neck bass which I had fitted with a Fender pickup. After the album I traded it for a Fender Precision . The Ampeg ended up with Phil Chen. He recently told me that it was stolen from him in Jamaica. My next main bass up until 1977 was a maple neck Precision I bought new in 1972 in New York. I tried six in the Sam Ash store before making a choice, and the salesman was getting quite irate! It is on the second and third Vinegar Joe album and countless sessions. In 1974 I bought a new maple neck Fender Jazz bass. These are two of my favourite basses. Both are on Elkie Brooks’ “Two Days Away” album and many other recordings. Here is a video with the 1972 Precision. |

Gli amplificatori che ho usato di più durante gli ultimi due anni sono un Fender Rumble 500 e 100, anche sul palco dei concerti. Per i palchi grandi collego due 500. Così qui suono bassi costosi con amplificatori economici! Ma alla mia età, mobilità e convenienza sono fondamentali perciò mi fanno i complimenti sul suono. Di seguito c’è una lista di alcuni dei miei bassi preferiti del passato. Comprai il mio primo Fender nel 1968. Era un usato del 1964. Il basso era quello impiegato nell’album East Of Eden e sul primo dei Manfred Mann Chapter 3. Usavo corde del tipo flatwound sempre su East Of Eden. Non appena uscì il Rotosound swing Bass con le corde di tipo roundwounds cambiai ma erano troppo leggere per me così usavo un Re al posto del Sol, ed un La al posto del Re, un Mi al posto del Re. Comprai delle corde LaBella tapewound in nylon e raschiai il nastro adesivo! Gli amplificatori di basso nel Regno Unito erano terribili allora! Usavo due cabs da 18” con un Selmer amp da 100 watt. Per darci un taglio, con i Manfred usavo spesso dei plettri in metallo sulla punta delle mie dita. Le corde Rotosound prevedevano i tasti perciò scambiai il basso con un jazz bass del ’64 e vendei il manico per un P Bass, che è lo strumento che ho usato nel secondo album dei Manfred Mann. Quando eravamo sul punto di registrare il primo album dei Vinegar Joe volevo ottenere un suono differente così comprai un Ampeg scroll neck bass degli anni ’60 che associai ad un pickup Fender. Dopo l’album lo scambiai con un Fender Precision. L’Ampeg è finito a Phil Chen. Recentemente mi ha detto che gli è stato rubato in Jamaica. Il mio basso successivo fino al 1977 fu un maple neck Precision che acquistai nuovo nel 1972 a New York. Ne provai sei nel negozio Sam Ash prima di fare la mia scelta, ed il venditore stava diventando abbastanza iracondo! Lo si può sentire sul secondo e terzo album dei Vinegar Joe e su infinite sessions. Nel 1974 comprai un new maple neck fender Jazz bass. Si tratta di due dei miei bassi preferiti. Ci sono entrambi nel disco di Elkie Brooks “Two Days Away” e in molte altre incisioni. Qui c’è un video con il Precision del 1972. |

|

In 1976 I bought a 1957 Precision which was my main live bass up to 1988. I sold it in 2001. In 1978 I sold my 70’s Fender basses to buy an Alembic Series 1 that was John Entwistle’s first Alembic. It was my main studio bass up until 1985 but was impractical to play live. Here is a video of me playing it with Elkie Brooks. |

Nel 1976 comprai un Precision del 1957 che è stato il mio basso principale dal vivo fino al 1988. L’ho venduto nel 2001. Nel 1978 ho venduto il mio basso Fender degli anni ’70 per comprare un Alembic Series 1 che è stato il primo Alembic di John Entwistle. È stato il mio primo basso da studio fino al 1985 ma era poco pratico da suonare dal vivo. Qui c’è un video di me mentre suono con Elkie Brooks. |

|

My main bass from 1988 to 2001 was a 1964 Jazz bass with Alembic pick ups and preamp. In 2001 I started playing Lakland basses, and then sold my Fenders to buy my Fodera basses.